This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

The Sixth and the Ninth Symphonies of Vaughan Williams make apt discmates. Both share the same home key of E Minor, and open in dark, dramatic conflict but close in quiet, unresolved mystery. (Regarding the finale to the Sixth, RVW quoted the famous lines from Shakespeare’s The Tempest: “We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.”) Both also exemplify the exploration of new instrumental colors and more dissonant harmonies that became signatures of the composer’s late period compositions.

The Symphony No. 6 was composed in 1944–47 and premiered on 21 April 1948 by Adrian Boult and the BBC Symphony. Initial reviews were uniformly laudatory, if somewhat patrician in tone, as illustrated by Ernest Newman’s notice in the Sunday Times on 25 April 1948: “Whether Vaughan Williams's new symphony … will soon achieve the popularity of some of its predecessors I cannot say;… but it is clear already that here we have a new Vaughan Williams, and a Vaughan Williams at the height of his powers. Superficially it links up in mood now with the vehement Fourth, now with the mysticism of certain others of his works. But it would be a mistake to regard the No. 6 as merely a re-travelling, even a superior re-travelling, of the old routes. It reveals a new order of ideas and a new logic in the handling of them. It is the work of a mind at once sensitive and powerful that at long last has succeeded in bringing its whole kingdom of thought and emotion under unified control; and in the light of it we shall now be able to listen to the composer's older works in a new way.”

Just as the Fourth Symphony was for some time seen as a harbinger of the violence that overtook Europe in the 1930s and 1940s with fascism and war, the Sixth was likewise initially viewed as a “war” symphony. While such interpretations fiercely annoyed RVW, in the case of the Sixth it fitted the public mood, and the work was embraced enthusiastically. The first two recordings of it were made almost simultaneously, by Leopold Stokowski and the New York Philharmonic on 21 February 1949, and by Boult with the London Symphony on 23–24 February. In 1950 RVW significantly revised the scherzo movement; Boult promptly recorded the new version, which displaced the previous one in 78rpm and LP releases, though CD releases have featured both.

The Ninth Symphony, composed in 1956–57, was premiered by Malcolm Sargent and the Royal Philharmonic on 2 April 1958 (the broadcast of that performance was previously released on PASC234). As with the Eighth Symphony, it left most critics nonplussed; Harold C. Schonberg in the New York Times was virtually alone in hailing it “a masterpiece.” In the Manchester Guardian on 3 April, Colin Mason sniffed, “The key is E minor, the same as that of the sixth, and the composer has followed the precedent he set with that work of introducing his symphonies with a facetious analytical programme note of his own, in which he tilts at the professional analysers of musical forms…. Other strange notions nod in this composer's head. There is a march theme in the slow movement described by him as ‘barbaric.’ Later in the movement there is a ‘menacing’ stroke on the gong, introducing a ‘sinister’ recapitulation of an earlier theme…. The gong stroke makes no effect at all, and the supposedly barbaric march theme, in the pseudo-Chinese vein of the Eighth Symphony, is the silliest and poorest music in the work.” Three days later in the same publication, Adam Bell, while more positive in overall tone, observed: “[T]o complain that Vaughan Williams's Ninth lacks a coherent and consistent programme is really another way of saying that it does not quite convince as a piece of music. As a composer Vaughan Williams has always appeared to work best in response to the stimulus of an idea which, in musical terms, may be called philosophic; his most satisfying symphonies – 4, 5 and, perhaps, 6 – are all undeniably ‘about’ something. The new work does not seem (after two hearings) to have been written under the same pressure of experience.” As is now known, the Ninth originally did have a programmatic basis, in Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles, with draft references to Stonehenge, Salisbury Plain, Wessex, and Tess herself, all deleted before the score was finished. While the Eighth unjustly still languishes as RVW’s least often performed symphony, in recent decades the Ninth has won increased understanding and popularity, as a fitting capstone to the composer’s compositional career.

JAMES ALTENA

BOULT Vaughan Williams Symphonies Volume 5

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No. 6 in E minor

1. 1st mvt. - Allegro (8:20)

2. 2nd mvt. - Moderato (10:18)

3. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo: Allegro vivace (6:59)

4. 4th mvt. - Epilogue: Moderato (13:19)

5. VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Speech after the recording of Symphony No. 6 (1:19)

6. SIR ADRIAN BOULT Introduction to Symphony No. 9 (0:27)

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No. 9 in E minor

7. 1st mvt. - Moderato maestoso (9:17)

8. 2nd mvt. - Andante sostenuto (8:05)

9. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo: Allegro pesante (5:36)

10. 4th mvt. - Andante tranquillo (11:52)

London Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Sir Adrian Boult

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

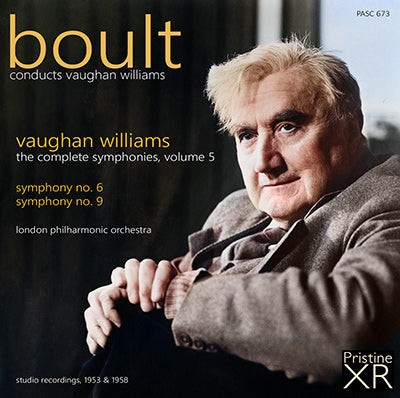

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Vaughan Williams

Symphony No. 6 (Ambient Stereo)

Recorded Kingsway Hall, London, 2, 3, 5 & 30 December 1953

Engineered by Kenneth Wilkinson

Produced by John Culshaw and James Walker

Recording supervised by the composer

Symphony No. 9 (stereo)

Recorded Walthamstow Assembly Hall, 26-27 August 1958

Produced by John Carewe

Total duration: 75:32