This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Reviews: Dvořák

- Review: Janáček

During the early part of his career there were three works that Jascha Horenstein used as his musical calling card - Mahler's First Symphony, Schoenberg's Verklaerte Nacht and Dvořák's Ninth Symphony - and all three remained staples of his regular repertoire. The 'New World' Symphony presented here dates from 1952 and was the first of his many recordings for Vox Records, the label that so defined a good part of his career, some would say unfortunately. It was also Horenstein's first post-war engagement with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, his professional debut orchestra that he had last conducted in 1928, an era away. The sessions took place at the orchestra's own Symphonia Studio and were immediately followed by his celebrated recordings of Mahler's Ninth and Shostakovich's Fifth, the whole project completed in less than two weeks during which, in keeping with the Vox's method of work, there was no time for retakes or corrections. Not a brilliantly colored or flashy performance, Horenstein's affectionately moulded 'New World' was praised for its artful and subtle control of line and expression, “shaped with a tenderness that rekindles interest in familiar phrases”, as Andrew Porter put it in a oft-repeated observation about much of Horenstein's work. For Berthold Goldschmidt the “springy rhythms and flexible rubato turns” in the Trio of the scherzo movement were particularly felicitous touches and examples of Horenstein's exacting demands on the skills of his players. One of its early admirers was a young musician in South Africa named Ernest Fleischmann, later the influential manager of the London Symphony Orchestra, who attributed his first interest in Horenstein to this recording.

An early and long time advocate for the music of Leoš Janáček, whom he admired for his independent thinking and freedom from contemporary influences, Horenstein described his 1927 meeting with the composer evocatively and amusingly in a number of interviews. Following that meeting he attended the German premiere of the 'Sinfonietta' conducted by Klemperer in Berlin, gave the Viennese premiere of the same work in February 1928 and conducted seven performances of 'House of the Dead' in Düsseldorf during the 1931/32 season. After the war Horenstein did much to champion Janáček's music on radio, on records and in concerts, including the Argentine premiere of the 'Sinfonietta' in Buenos Aires in July 1951, the French premiere of 'House of the Dead' in Paris in May 1953 and the American premiere of 'The Makropulos Case' in San Francisco in November 1966, and probably would have done more had life dealt him a different set of cards. The present recording of 'Taras Bulba' derives from a radio broadcast of the first of two concerts he gave with the Berlin Philharmonic at the 1961 Edinburgh International Festival, last minute engagements after Rafael Kubelik canceled following the death of his first wife. The second concert a day later featured Horenstein's incandescent performance of Mahler's Fifth Symphony, first published on this label in 2014 (PASC 416). Recordings of both concerts, broadcast live during a particularly delicate period of the Cold War, document an orchestra in top form and in complete harmony with the conductor. Then nearing the peak of his powers and with over a decade still to live, it remains a mystery why, having rescued the orchestra from a difficult situation for an important international event, Horenstein was never invited to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic again.

Misha Horenstein

Horenstein conducts Dvořák & Janáček

DVOŘÁK Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95, 'From the New World'

1. 1st mvt. - Adagio - Allegro molto (9:52)

2. 2nd mvt. - Largo (14:25)

3. 3rd mvt. - Molto vivace (8:38)

4. 4th mvt. - Allegro con fuoco (11:44)

Vienna Symphony Orchestra

5. RADIO Taras Bulba Introduction (0:41)

JANÁČEK Taras Bulba, Rhapsody for large orchestra

6. 1. The Death of Andrei (8:25)

7. 2. The Death of Ostap (5:56)

8. 3. The Prophecy and Death of Taras Bulba (9:00)

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Jascha Horenstein

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Source recordings and artwork from the archives of Misha Horenstein

Dvořák recorded at Symphonia Studio, Vienna, 4-6 April 1952

Janáček live broadcast performance, Usher Hall, Edinburgh, 30 August 1961

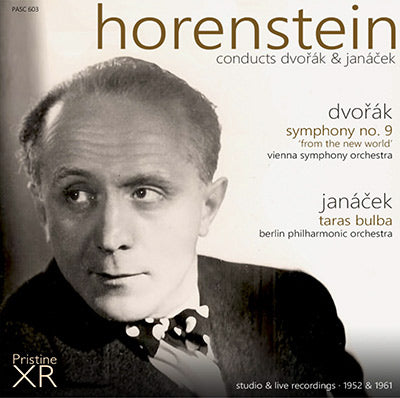

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Jascha Horenstein

Total duration: 68:41

The Gramophone, November 1953

Previous New Worlds have not been altogether satisfactory, but the present

Vox issue is more than acceptable and the best of the three LP versions

available. The Decca one (New Symphony Orchestra under Jorda) is

unidiomatic, and dimly recorded. Kubelik's with the Chicago Symphony

Orchestra (a Mercury recording released in England by H.M.V.) could not be

called dim—on the contrary, for a good deal of the time the tone has an

almost unnatural brightness. But Kubelik overplays the work. The Larghetto

is fast, insensitively fast; the outer movements are driven. Jascha

Horenstein, with far less daemonic energy, almost leisurely at times,

elicits in fact a performance of far greater vitality—because his phrases

are sensitively and feelingly shaped. A comparison of the opening passages

of the third movement is an easy and fair one to make—and decisive in

favour of the Vienna disc. The Vox recording is excellent; if it never

quite achieves the startling brilliance of Mercury's “Living Presence”, it

is also free from the faults of the H.M.V. Record. This is a performance

one could live with.

Andrew Porter, The Observer, 25 October 1953

The best of the 'New Worlds' is a new Vox made by Jascha Horenstein .

The Gramophone, February 1954

To reassure myself that I was not just getting tired of the work, I went back to the Vox disc by Jascha Horenstein and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra (PL7590).

Comparative review by David Hurwitz, ClassicsToday.com

Now, however, we come to a fine “From the New World” Symphony recorded in 1952 and captured in very clear mono sound with appropriately forward woodwind balances. Granted, the Vienna Symphony Orchestra isn’t going to win any major awards for tone quality: grainy cellos, edgy brass, and the occasional sour oboe point to a typically post-War European orchestral experience. What’s far more important, though, is how carefully Horenstein makes his band observe Dvorák’s detailed phrasing and accent marks, and how flexible this performance is tempo-wise. And as luck would have it, Horenstein re-recorded the work in 1962 with the Royal Philharmonic in stereo, also a very fine performance in which we can clearly hear the conductor “de-Romanticizing” his style while still retaining significant elements of the earlier performance. Let’s compare the two and see what we can learn.

The first movement introduction (’52) contains a near disaster, when the horns enter a beat early for all of their fortissimo eruptions beginning at bar 10. This should have been corrected. In both versions, Horenstein launches the first movement allegro with great energy. The 1952 ensemble balance highlights the clarinet over unison flute and oboe in the transition to the second subject despite the composer’s clear dynamic markings to the contrary–an interesting touch all the same. When the famous flute theme arrives, Horenstein gets some lovely, elegant phrasing from his Viennese players, while a decade later he’s a shade less generous with his rubato at a marginally faster tempo. Although I miss the extra affection of the earlier version, the later one sets up the transition to the development better and maintains a higher energy level. Finally, in 1962 Horenstein had much better horn players, and evidently didn’t feel the need for the big ritard introducing the coda (letter M) that we hear ten years previously.

The Largo reveals the biggest differences between the two recordings. Horenstein takes two extra minutes in 1952 (14+ minutes in all), and while the English horn player hasn’t the most lovely timbre, he phrases sensitively and in tune. The very slow tempo compared with 1962 makes for a much larger, even abrupt contrast between the first and second themes. However, the London Horenstein retains the speed-up, slow-down treatment of the quiet string passage at measure 30, as well as the strictly in tempo approach to the big climax. At the movement’s end in the earlier version, at the top of the main theme’s concluding phrase (measure 113) as played by the strings for the last time, Horenstein inserts a stunningly effective sforzando that’s sadly absent in the remake. And if the 1962 scherzo has greater energy at a swifter tempo than this one, the earlier version has two lovely touches that vanish later: a sweet little ritard at the end of trio’s second half (both times around), and an uninhibitedly ferocious return to the scherzo proper.

Both finales treat the opening in the brass as a slow introduction, and then accelerate impulsively to the string’s triplet theme at letter B. Once again, the earlier effort exploits this contrast more boldly than the later one. In both versions, however, Horenstein is one of the very, very few conductors who get the cymbal part right: suspended and struck with a soft stick, rather than two plates clashed. This isn’t an especially important matter, but it is indicative of the conductor’s attention to the finer points of detail, a characteristic of both performances. The mono recording’s focus on the winds invests the finale’s development section with plenty of color and rhythmic interest, and Horenstein has the strings attack their wild triplets at the big climax just before the coda with impressive power. In 1962, there’s less emphasis on expressive shaping of details and a stronger sense of linear continuity, while both recordings bring the work to an exciting close.

Glasgow Herald, 31 August 1961

After the somewhat enigmatic Karajan, and the fastidious discipline of Kempe, the Berlin Philharmonic were conducted at the Usher Hall last night by Jascha Horenstein. And a missing musical link fell into place.

Greatness, majesty, mastery: these we had been given in previous concerts, yet there had been a certain aloofness, a detachment. Hard to place, for there was nothing to fault in the superb playing. We felt as Francis Thompson felt about Milton, that with Karajan and Kempe we had music making to which we must all bow the knee, few or none the heart.

Last night we bowed the heart to Horenstein. There is a homeliness about him, a sense of affection which draws a spontaneous response from his players. They were "with" him, eager, ardent. He can be stern, but it is a kindly, patriarchal sternness.

The programme gave us Gluck, Janacek and Beethoven, and heroic as the "Eroica" admittedly is, and heroically as it was given full value last night, to some of us the most rewarding playing came in the "Taras Bulba" of Janacek.

It is "story" music, illustrative, a music drama without words, and it answers the snooty cliques who affect to disdain any music that dares to paint pictures, bring out an emotion: any music that has in its veins warm, pulsing, passionate blood in-place of the desiccated sawdust of a later Schoenberg.