This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

Fritz Busch’s (1890–1951) affinity to the music of Johannes Brahms gestated from fairly early in his life, not least when he was a student at the Cologne Conservatoire from 1906 to 1909. One of his teachers there was Fritz Steinbach (1855–1916), a noted Brahmsian, who had closely collaborated with the composer from at least 1886 and who became a kind of father-figure to Busch (Busch calling his mentor “uncle” from soon after he had left the Conservatoire). As Christopher Dyment, who has in detail studied the early recorded performances of the Brahms symphonies in comparison to those of several other conductors, wrote: “More than any other recording conductor he had the chance to observe and absorb the Steinbach method and style”,[1] and although they had their differences over stick technique, this was soon forgotten and Steinbach eventually became godfather to Busch’s first child, son Hans Peter, in 1914.

The close Brahmsian connection resulted in Brahms’s music featuring regularly in Busch’s orchestral concerts, from as early as his first appointment, in Bad Pyrmont, on 22 July 1909. Busch was particularly interested in performing Brahms’s Symphonies Nos. 1, 2 and 4 as well as the ‘Haydn’ Variations and the Violin Concerto, each of which works he conducted at least twenty times. While however renderings of neither the Violin Concerto nor the ‘Haydn’ Variations conducted by Busch seem to have survived, so has a performance of the First Symphony, aired on 1 February 1942 from New York’s Carnegie Hall. This performance has survived in several collections in varying quality, including the Minneapolis Public Library and private collections in Europe and abroad, but has never before been issued on LP or CD. Christopher Dyment has stressed this performance to be “as remarkable as the 1931 broadcast performance of the Second Symphony”.

His earliest ascertained rendering of Symphony No. 2, in D major, took place during the above-mentioned debut concert in Pyrmont. A famed performance of the work, by the Saxonian Staatskapelle Dresden in Berlin on 25 February 1931, was transmitted on radio and has been subsequently released on CD.[2] Sixteen years later, in cold October 1947, Busch recorded the symphony for The Gramophone Company Ltd. (as a short break from Macbeth performances in Stockholm), the recording (which was sold out in New York by Christmas 1949) being hailed by the press as exceptional: “the Danish strings are radiant in the first movement, the tart winds at the opening of the Andante grazioso lend a piquant flavor, and the driving last movement is rousing. Busch’s Adagio is noteworthy for its tenderness, even at a fluid tempo considerably faster than Bruno Walter’s reading of that movement” (Dan Davis in Classics Today). And John Gray (in the Design Review) stated that “one is glad to note that the Danish set is excellent in every way, both as performance and recording.” Busch had taken over the post of Principal Conductor of the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra in 1937 and held this position until his death; during the war he had been forced to stay away from Denmark, and Kai Flor (in the Belingske Tidende) described the performance of the symphony on 10 October 1946 as Busch “embracing the symphony and penetrating it with his warm musical feeling, educing strength, gentleness, grace, bright humour and eventually subdued mysticism from it, well into the radiant, percussive festiveness of the finale. What a richness, what a beauty of thoughts, of feeling, of soul! – Yes, for this we had waited for six years!” And ‘Schap.’ in the Børsen wrote: “Under Busch’s hands all the symphony’s vitality and spontaneous zest for life were released – he can work with an orchestra so that it sings and sounds beautifully, and at the same time clarify the overall form, as if one has the feeling of the work just being created.” Like Weingartner and Toscanini, Busch’s Brahms features brisk tempos, clear textures, and firm rhythms (all, according to Walter Frisch, hardly to be linked with Steinbach’s performing tradition), but these attributes are leavened by a warmth that sometimes eluded the other two conductors – the latter quality undoubtedly being imparted by Steinbach.

While renderings of neither the Violin Concerto nor the ‘Haydn’ Variations conducted by Busch seem to have survived, so has a performance of the First Symphony, aired on 1 February 1942 from New York’s Carnegie Hall. This performance has survived in several collections in varying quality, including the Minneapolis Public Library and private collections in Europe and abroad, but it has never before been issued on LP or CD. Christopher Dyment stresses this performance to be “as remarkable as the 1931 broadcast performance of the Second Symphony”. [3] “In his interpretation, much of the first movement and the whole of his electrifying finale for the most part ring true as remarkable recreations in the spirit of his teacher [Steinbach]; so, too, do his broad, flexible but never inflatedAndante second movement and his free-flowing but never pressurized Allegretto third movement [...] Busch’s Brahms First Symphony must be counted among the prime documents available in the task of reconstructing the Meiningen way.” [4]

In September 1950 Busch conducted his last of a total of some 14 performances of Brahms’s Tragic Overture at the Danish Radio Concert Hall. Grete Busch recalls that “a golden Danish autumn” was kind of reflected in the delighted and delighting concert, which apart from the Tragic Overture featured Brahms’s Nänie, Op. 82 (which sadly has survived only incomplete and appears, in a reconstructed version, for the first time [5]), and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the critics praising “noble lines” and “real Brahmsian temperament”. (One year previously, on 6 October 1949, another Brahms performance had been broadcast from Copenhagen, a famed Alto Rhapsody starring English mezzo-soprano Kathleen Ferrier; [6] we are lucky that further to this performance also another one, dated 10 December 1950, given at the Human Rights Day Declaration for the United Nations concert in New York, this time starring American Marian Anderson, has survived and is available for comparison with the Danish performance. [7])

The very same month Busch visited war-ravaged Vienna, where he made some LP recordings with the Niederösterreichisches Tonkünstler-Orchester for the Remington label, of music by Beethoven and Haydn, where he conducted several opera performances (which were intended as a kind of signal of him returning from the season 1951/2 onwards as music director of the Vienna State Opera, which alas, due to his untimely death was not to happen), and conducted some orchestral concerts, both with the Wiener Philharmoniker and with the Symphoniker. This latter concert, which was broadcast by Radio Rot-Weiß-Rot and has survived on tape, took place at the Musikverein on 15 October, featuring Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony in A, Op. 92, and Brahms’s Fourth Symphony in E minor, Op. 98, giving us ample opportunity to admire Busch’s conducting. The performance combines a great sense of authority with a deep understanding of the music. Harris Goldsmith describes the Brahms performance as “galvanic”, the whole performance having “a wonderfully granitic firmness of outline, with plenty of sentiment but no trace of sentimentality. And, save for one or two ever-so-slightly idiosyncratic details (probably arising from the heat of the moment), the final Passacaglia is admirably steady.”

Jürgen Schaarwächter

Max-Reger-Institut with BuschBrothersArchive, Karlsruhe

Master source: BrüderBuschArchiv in the Max-Reger-Institut, Karlsruhe; Minneapolis Public Library; Private collection, kindly supplied by the late Christopher Dyment

Remastering: Andrew Rose

All images courtesy of BrüderBuschArchiv in the Max-Reger-Institut, Karlsruhe

[1] Christopher Dyment, Toscanini in Britain, Woodbridge: Boydell, 2012, p. 317.

[2] Profil Hänssler PH07032 and Guild Historical GHCD 2371, released in 2008 and 2011 respectively, from dissimilar source material.

[3] Christopher Dyment, Conducting the Brahms Symphonies: From Brahms to Boult, Woodbridge: Boydell, 2016, p. 142.

[5] The Nänie was kindly edited by Andrew Rose, using short amendments from another performance, recorded in 1954 under Carl Schuricht.

[7] Guild Historical GHCD 2354, released in 2009.

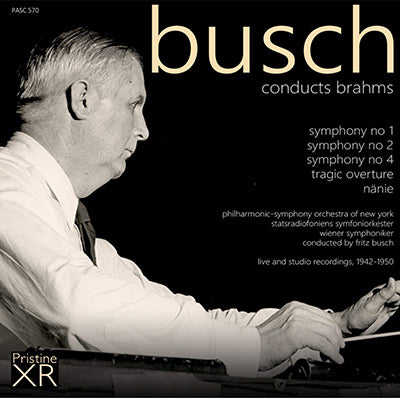

Fritz Busch conducts Brahms in New York, Copenhagen & Vienna

(1942, 1947 & 1950)

Disc One

BRAHMS Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

1. 1st mvt. - Un poco sostenuto - Allegro (13:23)

2. 2nd mvt. - Andante sostenuto (10:25)

3. 3rd mvt. - Un poco allegretto e grazioso (4:48)

4. 4th mvt. - Adagio - Allegro non troppo, ma con brio (16:32)

New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra

Carnegie Hall, New York, 1 February 1942

5. BRAHMS Tragic Overture, Op. 81 (13:07)

6. BRAHMS Nänie, Op. 82 (14:43)

Statsradiofoniens Kor

Statsradiofoniens Symfoniorkester

Danish Radio Concert Hall, Copenhagen, 7 September 1950

Disc Two

BRAHMS Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73

1. 1st mvt. - Allegro non troppo (13:18)

2. 2nd mvt. - Adagio non troppo (8:40)

3. 3rd mvt. - Allegretto grazioso (quasi andantino) (4:45)

4. 4th mvt. - Allegro con spirito (8:10)

Statsradiofoniens Symfoniorkester

Danish Radio Concert Hall, Copenhagen, 20/21 October 1947

BRAHMS Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98

5. 1st mvt. - Allegro non troppo (11:02)

6. 2nd mvt. - Andante moderato (10:57)

7. 3rd mvt. - Allegro giocoso (5:55)

8. 4th mvt. - Allegro energico e passionato (9:53)

Wiener Symphoniker

Musikverein, Vienna, 15 October 1950

conducted by Fritz Busch

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Fritz Busch in 1950

Special thanks to Dr. Jürgen Schaarwächter

Produced in co-operation with the Max-Reger-Institut/BuschBrothersArchive, Karlsruhe, Germany

Total duration: 2hr 25:36