- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

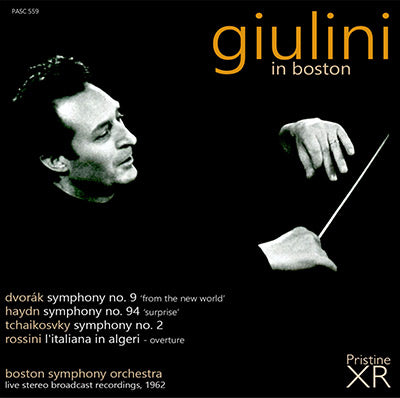

- Cover Art

"Carlo Maria Giulini was born in 1914 in Barietta, an ancient and historic city on the Adriatic coast in the south of Italy. He studied at the Academy of Santa Cecilia in Rome, and took a course in conducting under Alfredo Casella, and later under Bernardino Molinari at the Chigi Academy in Siena. He was engaged by the Italian Radio (RIA) in 1946 and in 1950 became the conductor of the orchestra of Radio Milano.

Through the past nine years his principal activities have been with La Scala opera in Milan. The performances directed by him there include: Monteverdi’s L’Incoronazione di Poppea, Stravinsky’s Les Noces (in its first Italian stage performance), Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle, Rossini’s La Cenerentola, and L’Italiana in Algeri. He has conducted at numerous festivals throughout Europe. He made his American debut conducting the Chicago Orchestra in 1955, and returned to this country in the autumn of 1960 as conductor of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. Mr. Giulini is now conducting in Boston for the first time."

From the BSO programme notes, March 1962

Of the major US orchestras, Giulini was most associated with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Following his 1955 debut he was its Principal Guest Conductor from 1969 to 1972, and continued to appear with them regularly until 1978. From 1978 to 1984, he served as principal conductor and Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Giulini’s performances with the Boston Symphony Orchestra were, by contrast, somewhat few and far between. He conducted the orchestra in some twenty concerts in total: seven in March 1962, eight in October and November 1969 and a final five in March and April 1974. The recordings here represent all we’ve managed to find from his 1962 concert broadcasts thus far. Captured in fine stereo sound and perfectly preserved over the intervening years, they are truly magnificent performances.

GIULINI in Boston, 1962

Disc One

HAYDN Symphony No. 94 in G, Hob.I:94 "Surprise"

1. 1st mvt. - Adagio cantabile - Vivace assai (9:39)

2. 2nd mvt. - Andante (6:33)

3. 3rd mvt. - Minuet - Trio (4:18)

4. 4th mvt. - Finale. [Presto] (4:35)

TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 2 in C minor, "Little Russian"

5. 1st mvt. - Andante sostenuto – Allegro vivo (11:07)

6. 2nd mvt. - Andantino marziale quasi Moderato (7:12)

7. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo. Allegro molto vivace (5:37)

8. 4th mvt. - Finale. Moderato assai — Allegro vivo (10:02)

Disc Two

1. ROSSINI L'italiana in Algeri - Overture (8:56)

DVOŘÁK Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95, "From the New World"

2. 1st mvt. - Adagio - Allegro molto (9:37)

3. 2nd mvt. - Largo (13:14)

4. 3rd mvt. - Molto vivace (7:52)

5. 4th mvt. - Allegro con fuoco (14:10)

Boston Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini

XR remastering by

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Carlo Maria Giulini

Live broadcast concerts:

2 March 1962 (Rossini, Tchaikovsky)

9 March 1962 (Haydn, Dvořák)

Symphony Hall, Boston

Total duration: 1hr 52:52

Fanfare magazine review

Giulini delivers bracing tempos; the Presto finale is as exhilarating as ever, with this magnificent orchestra in total command of every twist and turn

The 1962 Boston Symphony was the Rolls Royce of orchestras, purring along in high gear. The silky violins maintained full tone from pp to ff, never screeching, never drying. They were a perfect match with Carlo Maria Giulini’s gentle touch, sounding very different here from Charles Munch’s high-wire explosions. There’s much of Beecham’s bounce and elegance in the Haydn symphony; “Papa Haydn,” perhaps? A touch (the “Surprise” is the symphony most prone to such sentiment), but the performance is so beautiful we cannot complain. The only surprise is the “Surprise” chord itself, drawn out rather than clipped, which lessens its potency. The main signs of 1960s performance practice are soft-headed timpani and retards at cadential points. I suspect this is the full BSO, yet its strings are so smooth and subtle that winds are always given suitable prominence. The acoustic of Symphony Hall is gorgeous, if a touch reverberant—so are all the great halls. Giulini delivers bracing tempos; the Presto finale is as exhilarating as ever, with this magnificent orchestra in total command of every twist and turn.

The silky purring continues into The “Little Russian” Andante sostenuto, enough so to make one worry whether Giulini will lay bare all of Tchaikovsky’s drama. But he lets loose in the Allegro vivo, with crisp, Munchian brass attacks and hard drumsticks. I’ve always been disappointed by the “Little Russian,” a series of beautiful ideas that do not coalesce into a fine symphony; recent exposure (Fanfare 43:2) to all of Tchaikovsky’s operas has shown me how operatic this opening movement is. The Scherzo is taken at a slightly slower tempo than usual, with a crisp military mien; its coda will knock your socks off. The entrance of the finale’s second theme is incredibly tender. The orchestra is not quite perfect in some places; perhaps Giulini was adlibbing beyond rehearsal, and this was his very first appearance with the BSO. It remains a marvelous performance; with many interior details subtly brought forth.

The many oboe solos in L’Italiani in Algeri give us the opportunity to compare the Gomberg brothers: the BSO’s Ralph is smooth and correct; the New York Philharmonic’s Harold is sweet and vivacious. Giulini—now on his home ground—leads a superbly subtle performance, making Bernstein’s NYP seem loud and crass. One doubts that it ever went as well in Milan as in Boston. Yet the Philharmonic plays even more crisply for Bernstein, its excitement more than making up for the lack of subtlety.

After all this magnificence, it’s a shock to hear a “New World” that just doesn’t work; there is much virtuoso playing throughout, but it doesn’t add up to a satisfactory performance. The BSO’s sharp, bright French woodwinds are all wrong for Dvořák, especially when compared to the cool, mellow winds of the Czech Philharmonic. Perhaps that’s why the powers that be assigned Arthur Fiedler to conduct the BSO’s only complete recording of the “New World.” Strings are recessed now, with too much attention paid to the winds (oddly, a brief viola passage in the finale stands out); Roger Voisin’s blazing first trumpet upsets many ensemble passages. Tempos are unsteady. The English horn solo in the Largo is taken quite briskly (perhaps Giulini had seen the manuscript, where Dvořák first wrote Andante, then crossed it out and wrote Adagio, and finally Largo); late in the movement, Giulini suddenly slams on the brakes, catching the orchestra off guard for a moment. The Scherzo goes well, but the first section of its Trio is heavy-handed, almost lugubrious.

James H. North