- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

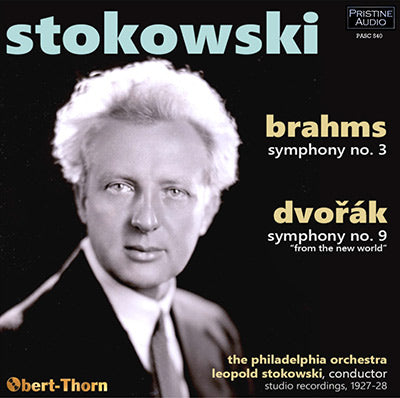

- Cover Art

It is difficult to believe that it was not until 1921 that the first recording of any portion of a Brahms symphony appeared on disc: the third movement of the Brahms Third Symphony, abridged to one 78 rpm side, and played by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra. When electrical recording appeared, the conductor went on to pioneer the earliest Brahms symphony cycle, beginning with the First in 1927 (Pristine PASC 500).

The Third was the next in the series to be recorded. Like the First, it was the symphony’s première electrical recording; but it was also the work’s first complete recording. It was hampered in two respects: by a finale which begins with an unusual (for Stokowski) lack of energy, and only really catches fire toward the end; and by the abrupt and frequent volume level changes imposed by the original engineer.

“Gain riding” was something of a necessary evil at the time in order to avoid loud passages causing a record to fail the “wear test”; but the recordings Victor made in late 1928 (including Mengelberg’s Ein Heldenleben as well as the present set) took knob twiddling to an irrational extreme, with volume levels suddenly going up and down seemingly at random throughout the set. Modern technology and painstaking, sometimes note-by-note work in this transfer have finally removed at least the most objectionable of these fluctuations, allowing listeners to hear it in an untampered form for the first time.

Despite its drawbacks, the set remained in the Victor catalogue through the end of the 78 rpm era, even making an appearance on RCA’s Camden LP label in the 1950s. The reason for both was probably the lack of a Stokowski remake until his Houston Symphony stereo LP appeared in 1959. While the conductor made several studio recordings of the First and Fourth Symphonies, the Second and Third only have two apiece; but unlike any of the other symphonies, live recordings of Stokowski in this work have not been forthcoming on CD, save for a private release of a 1941 NBC Symphony broadcast.

The Dvořák “New World”, on the other hand, was frequently recorded by Stokowski throughout his career. The version heard here was already his second electrical recording with the Philadelphians, superseding a 1925 effort with reduced personnel and acoustic-style re-orchestration. Like some other sets made by Stokowski and the Philadelphians in 1927 (the Beethoven Seventh, Brahms First and Franck Symphonies), it was accompanied in its American release by a separate disc with a discussion of the work spoken by the conductor. Unlike the Beethoven and Brahms discs in which Stokowski assumed both the speaking and piano-playing roles, the pianist here, uncredited on the original discs, was his Philadelphia assistant, Artur Rodzinski, in his first recording session.

The sources for the present transfers were Victor “Z” pressings for the Brahms (its quietest form of issue) and vinyl test pressings for the Dvořák. On its original release, the “New World” contained two dubbed sides – Side 2, the second half of the first movement, and Side 3, the first side of the second movement. I have used an unissued alternate take for the first movement side, but only the dubbed take still exists for the second movement.

STOKOWSKI conducts BRAHMS and DVOŘÁK

BRAHMS: Symphony No. 3 in F major, Op. 90

1. 1st Mvt.: Allegro con brio – Un poco sostenuto – Tempo I (9:48)

2. 2nd Mvt.: Andante (10:31)

3. 3rd Mvt.: Poco allegretto (5:51)

4. 4th Mvt.: Allegro – Un poco sostenuto (9:20)

Recorded 25/26 September 1928 in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Matrix nos.: CVE 46463-1A, 46464-1A, 46465-1A, 46466-1, 46467-2, 46468-1A, 46469-2A, 46470-2A, 46471-2A & 46472-2

First issued on Victor 6962 through 6966 in album M-42

5. Outline of Themes from Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 (4:03)

Leopold Stokowski (speaker)

Artur Rodzinski (pianist)

Recorded 6 October 1927 in the Victor Studios, Camden, New Jersey

Matrix no.: CVE 40401-2

First issued as Victor 6743 in album M-1

DVOŘÁK: Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 “From the New World”

6. 1st Mvt.: Adagio – Allegro molto (8:46)

7. 2nd Mvt.: Largo (12:08)

8. 3rd Mvt.: Scherzo (Molto vivace) (7:23)

9. 4th Mvt.: Allegro con fuoco (10:44)

Recorded 5 & 8 October 1927 in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Matrix nos.: CVE 32802-4, 32803-4, 33290-6, 33291-6, 33292-5, 33293-4, 33294-3, 33297-4, 33296-3 & 33295-3

First issued as Victor 6565 through 6569 in album M-1

The Philadelphia Orchestra ∙ Leopold Stokowski

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer:

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Leopold Stokowski

Total duration: 78:34

Audiophile Audition review

On every level, the orchestral execution and imaginative expression testify to a virtuoso display of American musicianship