This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- New York Times Article, 1943

There were times when I must have fantasized – you know, one of those days – "Someday, son, this will all be yours," as they say. But I never thought I would have to walk out there [the Carnegie Hall stage] on my own. When it came to the time – that very day – all I can remember is standing there in the wings shaking and being so scared. There was no rehearsal. I had just come from seeing Bruno Walter, who very sweetly and very quickly – wrapped up in blankets because he had the flu – went over the score of Don Quixote with me. He showed me a few tricky spots where he cut off here but didn't cut off there; here you give it an extra upbeat, and so on.

I called Mama and Daddy at the Barbizon to tell them and you [Burton]. And then I just had to hang around. I mean, I was all dressed; when it came to the crunch on that Sunday afternoon, I wore the one good suit that I had, a double-breasted suit. I had until 2:30 p.m. to kill before going to the hall in my sharkskin suit. In that hour or two, I sat in the drugstore [the Carnegie Hall Pharmacy, then located at the street level corner of the building]. I went in for some coffee. The druggist said, "What are you looking so pale about?" and he gave me two little pills, a green and red one. He said, "Look, before you go on, just pop these into your mouth. One will calm you down and the other will give you energy." I put them in my pocket.

The time seemed to hang heavy till 3:00 p.m., even though I had to go over some of the tricky spots in Don Quixote with the cello and viola soloists and the concertmaster. The thing that was obsessing me, possessing me, was the opening of the Schumann overture, which is very tricky because it starts with a rest – the downbeat is a rest. If they don't come in together, the whole concert is sunk. I mean, I can't once go 'bop, bop, bop,' and make sure they can do it. So, this was like a nightmare. I had to go on and do, untried, this thing of such difficulty. You know, I've heard other people come to grief in that opening bar. Then I finally went and talked with the guys and they said, "Good luck." Bruno Zirato said, "Hey, Lenny. Good luck baby." Oh, he was very fatherly and gave me big bear hugs. And that was about it.

As I was about to walk onstage, I remembered the pills. I took them out of my pocket, flung them as far away from me across the backstage as I could and said, "I'm going to do this on my own." I strode out and I don't remember a thing from that moment – I don't even remember intermission – until the sound of people standing and cheering and clapping.

From https://leonardbernstein.com/about/conductor/historic-concerts/the-debut-concert-1943

The story of Leonard Bernstein's remarkable concert hall debut with the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York on 14 November, 1943, crops up in many retellings. Yet it seems to have escaped any commercial release until now. The concert was broadcast live from Carnegie Hall by CBS radio, with Bernstein's triumphant stepping in for an ailing Bruno Walter at the very last minute, without rehearsal, making the front page of the following day's New York Times, alongside numerous war reports from around the world.

Bernstein knew Walter was unwell but only after spending the previous evening at a concert did he check over the scores before going to bed. The following morning the call came to say he would be taking the podium. There was no time to assemble the orchestra for any kind of run-through, so Bernstein had to settle for a visit and consultation with a blanket-wrapped Bruno Walter and a short time with the two soloists for Don Quixote, Joseph Schuster (cello) and William Lincer (viola).

As the New York Times reported, the concert was a huge success for the 25-year-old novice conductor, effectively launching his career on the world stage - and what a career that would go on to be.

Here we present the full radio broadcast, less the interval talk. Missing from the broadcast was the encore, but everything else has been preserved, including a very short summary of war news headlines that was included as part of the pay-off at the end of the broadcast.

The recording was made onto acetate discs from an off-air source, thus is of 1943 broadcast quality. I've managed to eliminate almost all the interference from another classical music broadcast which could just about be made out on the original recording (I thought at first it might have been a live Artur Schnabel concert which was being transmitted at the same time but the repertoire didn't match), and have done what I can with the condition of these elderly and somewhat worn discs. A handful of very short patches were required in two of the works to cover very short gaps in the source recording - these five patches have been digitally aged from more recent recordings to make their appearance as seamless as possible.

Some surface noise inevitably remains, and can be heard at different levels throughout the recording, parts of which are excellent considering the source, others less so. Overall this is good AM radio sound, and the listener will soon tune out of its shortcomings and become totally absorbed in this remarkable and truly historic performance.

Andrew Rose

BERNSTEIN'S NEW YORK DEBUT, 1943

1. Radio Introduction 1 (3:18)

2. SCHUMANN Manfred Overture, Op. 115 (12:07)

RÓZSA Theme, Variations and Finale, Op. 13a

3. Theme (0:31)

4. Variation 1 (1:40)

5. Variation 2 (1:09)

6. Variation 3 (1:08)

7. Variation 4 (2:56)

8. Variation 5 (1:05)

9. Variation 6 (2:28)

10. Variation 7 (1:10)

11. Variation 8 (1:28)

12. Finale (3:55)

13. Radio Introduction 2 (0:41)

R. STRAUSS Don Quixote, Op. 35

14. Introduction (5:48)

15. Theme (1:58)

16. Sancho Panza (2:32)

17. Variation 1 (1:31)

18. Variation 2 (3:41)

19. Variation 3 (3:50)

20. Variation 4 (1:47)

21. Variation 5 (3:44)

22. Variation 6 (1:07)

23.Variation 7 (0:48)

24. Variation 8 (1:33)

25. Variation 9 (1:01)

26. Variation 10 (4:05)

27. Finale (4:50)

Joseph Schuster, cello

William Lincer, viola

28. Radio Outro, News Headlines, Sign off (2:35)

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York

conducted by Leonard Bernstein

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

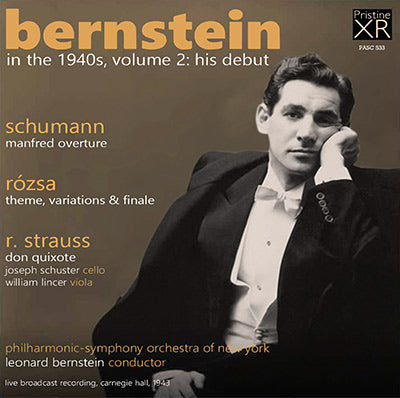

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Leonard Bernstein

Live CBS broadcast from Carnegie Hall, New York City, Sunday 14 November 1943

Introduced by Bernard Dudley

Total duration: 74:26

Young Aide Leads Philharmonic, Steps In When Bruno Walter Is Ill

A nation-wide radio audience and several thousand persons in Carnegie Hall were treated to a dramatic musical event yesterday afternoon when the 25-year-old assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra Leonard Bernstein, substituted on a few hours’ notice for Bruno Walter, who had become ill, and led the orchestra through its entire program.

Enthusiastic applause greeted the performance of the youthful musician, who went through the ordeal with no signs of strain or nervousness. Artur Rodzinski, the orchestra’s permanent conductor and musical director, who arrived at intermission time after motoring from his home in Stockbridge, Mass., declared the young man had “prodigious talent,” adding that “we wish to give him every opportunity in the future.“

Mr. Bernstein, appointed to his post at the beginning of the current season, was notified of Mr. Walter’s illness in the morning by Bruno Zirato, assistant manager. Mr. Walter, who was said to be suffering from a stomach disorder, was to have been the guest conductor for the afternoon performance, broadcast over the Columbia network.

The young conductor, a native of Lawrence, Mass., and a Harvard graduate, had no opportunity for rehearsal before opening the program with Schumann's Overture to “Manfred.” The program also included Rozsa's “Theme, Variations and Finale”; Strauss’ “Don Quixote” and Wagner’s Prelude to “Die Meistersinger.”

Mr. Bernstein received hearty applause at the end of the Schumann overture, but was recalled four times when he concluded the Rozsa variations. The audience warmed increasingly to his performance during the remainder of the program and. at its end, was wildly demonstrative.

After the performance Mr. Bernstein disclosed that he had been told on Saturday evening that Mr. Walter was ill and that he “might” be called upon to take his place at Sunday's concert. The possibility seemed remote, and the young man went to a song recital. When he got home, however, he decided to look over the scores of the Philharmonic program “just in case.”

“I stayed up until about 4:30 A. M., alternately dozing, sipping coffee and studying the scores," he said. “I fell into a sound sleep about 5:30 A. M. and awakened at 9 A. M. An hour later Mr. Zirato telephoned and said: “You're going to conduct.”

"My first reaction was one of shock. I then became very excited over my unexpected debut and, I may add, not a little frightened. Knowing it would be impossible to assemble the orchestra for a rehearsal on a Sunday, I went over to Mr. Walter’s home and went over the scores with him.

"I found Mr. Walter sitting up but wrapped in blankets and he obligingly showed me just how he did it."

Mr. Bernstein said he was too intent on his work to feel nervous during the performance.

By a happy coincidence, Mr. Bernstein’s father and mother, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Bernstein, had come from their home in Sharon, Mass., to visit their son and so they were able to attend the concert. Mr. Bernstein’s 12-year-old brother, Burton, also was with his parents.

Mr. Bernstein attended the Boston Latin School before entering Harvard, where he majored in music, studying composition under Walter Piston and Edward Burlingame Hill and piano with Heinrich Gebhard. He was graduated in 1939. He spent the next two years at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, where he worked under Fritz Reiner in conducting and Randall Thompson in orchestration.

Continuing his piano studies under Mme. Isabella Vengerova, he was accepted by Sergei Koussevitzky and trained by him in conducting at the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood, Mass. He returned as Mr. Koussevitzky’s assistant in the summer of 1942 after spending the winter season in Boston teaching, composing and producing a number of operas for the Institute of Modern Art in that city. It was during this season that his Clarinet Sonata had its first hearing.

Mr. Bernstein has been continuing his composing here for the last year and his First Symphony is to have its première under Mr. Koussevitzky with the Boston Symphony this season.

The New York Times, Monday November 15, 1943

Fanfare Review

Enthusiastically recommended

This concert preserves Leonard Bernstein’s headline-making professional conducting debut with the New York Philharmonic at age 25. At the time Bernstein was the orchestra’s official assistant conductor under principal conductor Artur Rodziński. Bruno Walter was scheduled to conduct. The evening before, Bernstein attended a concert by mezzo-soprano Jennie Tourel, which included a performance of his own song cycle I Hate Music. Despite being advised during the concert that Walter was not feeling well and to be on standby, he went to an all-night party afterwards at Tourel’s apartment, staying until somewhere between 4:30 am and dawn. He returned to his own flat, flipped through the scores again, fell asleep, and was awakened at 9:00 am by a phone call advising him that Walter was sick with the flu and that he would have to conduct the concert—a Sunday afternoon national broadcast over CBS Radio—with no time for a rehearsal. Unnerved, Bernstein asked if he at least could meet with Walter to go over the scores with him. This was arranged, and Bernstein was brought up to Walter’s hotel room. As he later recounted in an oral interview:

“He was very, very gracious. He was sitting huddled up in a blanket, poor man, sweating and shivering and what-not. And in the midst of all that misery of his, he was so kind and so helpful to me. I was there an hour, in the course of which he showed me various places [in Don Quixote] where he cut off first and made a Luftpause and then gave an extra upbeat here, and therefore I could be helped and in front of the orchestra wouldn’t be ragged. He was very helpful; I don’t know what I would have done without that hour with him and he gave it to me under great duress.”

Bernstein’s family, already in town for Tourel’s performance, was seated in the conductor’s box. No-one told him that Rodziński, who was in Stockbridge, CT and could have returned in time to lead the concert, had declined to do so, curtly responding when contacted, “Call Bernstein. That’s why we hired him.” (Rodziński actually did return in time to hear the second half of the program.) Although a friendly druggist had given Bernstein two pills for nerves and energy, Bernstein flung them away just before walking out on stage, saying to himself, “I’m going to do this on my own.”

With a supportive orchestra and sympathetic audience pulling for him, Bernstein’s debut was a triumph. The next day the New York Times ran the debut as a headline story, “Young Aide Leads Philharmonic; Steps in When Bruno Walter is Ill,” and an accompanying editorial remarked: “It’s a good American success story. The warm, friendly triumph of it filled Carnegie Hall and spread far over the air waves.” And, to invoke the old cliché, the rest is history.

This disc presents the broadcast portion of the complete concert. The final work on the program, the Overture to Wagner’s Die Meistersinger, was not broadcast due to time constraints, and with that also was lost the tumultuous ovation that the Carnegie Hall audience gave Bernstein at its finish. Certainly, though, the ovation after the Don Quixote is enthusiastic enough to give an idea of what occurred at the concert’s close.

Three key questions that arise here. How good are the performances? How good is the sound quality? How much of what is heard is genuine Bernstein, and how much is the orchestra playing for Walter with Bernstein primarily directing traffic?

To address those in reverse order, the third question is essentially unanswerable. Surely, a good deal of what is heard must necessarily be what the musicians imbibed from Walter in the course of rehearsal, and one can hear characteristically Walterian lyrical phrasing and weighty sonorities in many places. (To cite just one example, listen to the opening bars of the Langsam introduction to the Manfred Overture, where the almost sighing expression of grief in the violins, and the warmly supple tones and subtle swells in the lower strings, immediately speak of Walter’s handiwork.) Yet, just as surely, Bernstein was doing much more than just beating time (even if, by his own account, in the Strauss he had to work hard just to “hang on”), and much of the febrile energy of the playing must surely be due to his own skill. Even if he did largely preserve Walter’s coaching in the piece, that in and of itself would be no small accomplishment.

The sound quality is above average for a broadcast of this period, though there is some background shellac noise at points and some congestion and distortion at climaxes in the Don Quixote. The New York Philharmonic previously issued the virtually identical contents (Pristine preserves about two additional minutes of the closing station announcements) on a promotional CD in late 1996 to benefit the orchestra’s pension fund, but that disc has of course long been unavailable. This new version from Pristine clearly comes from a comparable source. It is remastered at a noticeably higher level, and also is slightly less filtered in the treble frequencies. The result is a trade-off according to tastes; Pristine’s sound is more forward and slightly more open, but also retains more harshness. If you are one of the fortunate few who owns the original NYP issue, I wouldn’t see a need to trade that in for this one; but if you don’t have it, there’s likewise no need to pay a premium price on the used CD market for that older issue when this one is readily available at a reasonable price.

Finally, as for the performances themselves, they are all simply terrific. The Manfred Overture has a nervous, even whiplash intensity, as the doomed protagonist confronts his earthly end. Miklós Rózsa’s Theme, Variations and Finale is an early work (op. 13) originally dating from 1933 and dedicated to the composer’s wife; he later revised it, mostly by way of small excisions, and the latter version is heard here. (The Chandos recording led by Ramon Gamba, the only other one currently in print, presents the uncut original. Out of print recordings include ones led by James Sedares on Koch and two on LP—mono Decca and stereo RCA—conducted by Rózsa.) A melancholy theme of an unmistakably Hungarian folk music stamp is introduced by the oboe, and then taken through eight colorful variations of varying characters before a fugal finale brings the proceedings to a close. All in all, it sounds very much akin to Kodály. The Strauss tone poem receives the most dynamic and compelling reading of that work I’ve ever heard (though I admit it’s not a work I turn to often). The orchestra plays at the top of its game, and first-chair players Joseph Shuster and William Lincer excel as the elderly knight and his faithful squire. This is a very brisk reading—whereas most performances come in about 41 to 45 minutes, this times out at a mere 38:05—which in my book is all to the good.

In sum, we have here not just a truly historic occasion, but also a set of first-rate performances. Pristine is especially to be commended for providing 10 separate track points in the Rózsa work and 14 for the Strauss (the NYP issue allots each only one track). Enthusiastically recommended.

James A. Altena