This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- NY Times Concert Review

This final entry in the Walter conducts Brahms series features only one recording from the 1951 series around which it has been constructed, the previously unissued and stunning performance with Clifford Curzon of the Piano Concerto No. 1. The surviving source for this recording has suffered some mild deterioration over the last 66 years that can at times be heard, but never to the extent that it distracts from the performance - in this we have I hope largely achieved the wish of the New York Times correspondent who wished it "might have been transfixed and preserved immaculate for the generations" - if not quite immaculate, then pretty close to it. It's certainly a major addition to the Walter discography.

For the rest of this release I've had to sift through the archives - not all of Walter's 1951 performances survive, and there we no performances of either the German Requiem or the Alto Rhapsody in the series. The latter, from a 1941 Carnegie Hall performance appears here for the first time, whilst I decided on the Italian performance of the German Requiem for both better sound quality and an unusually slower tempo from Walter than the other performances captured at this time. In both cases I've done what I can with the archive material available to me - the age of the Alto Rhapsody is reflected in a limited frequency range, whilst there is some top end hash heard during some of the louder passages of the Requiem.

The

other two recordings here come from the same Hollywood Bowl performance

that appears on Volume 1 of this series, and yes, once again the

crickets make an appearance towards the end of the Haydn Variations!

Andrew Rose

DISC ONE

BRAHMS Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a*

1 Theme. Chorale St. Antoni (1:53)

2 I. Poco più animato (1:17)

3 II. Più vivace (1:02)

4 III. Con moto (1:52)

5 IV. Andante con moto (1:50)

6 V. Vivace (0:58)

7 VI. - Vivace (1:11)

8 VII. Grazioso (2:07)

9 VIII. Presto non troppo (0:59)

10 Finale. Andante (4:14)

11 BRAHMS Alto Rhapsody, Op. 53 (11:02)

Enid Szantho, contralto

BRAHMS Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op. 15

12 1st mvt. - Maestoso (20:49)

13 2nd mvt. - Adagio (13:36)

14 3rd mvt. - Rondo. Allegro non troppo (10:49)

Clifford Curzon, piano

DISC TWO

1 BRAHMS Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80* (9:27)

BRAHMS Ein Deutsches Requiem, Op. 45** (Sung in Italian)

2 I. Selig sind, die da Leid tragen (Ben è vero che gli affliti son beati) (10:03)

3 II. Denn alles Fleisch (Dell'erba al par la carne è vile) (14:00)

4 III. Herr, lehre doch mich (Dio, svelami tu) (10:01)

5 IV. Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen (Le tue dimore sono dolci invero) (5:01)

6 V. Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit (Voi avete qui dolor) (7:16)

7 VI. Denn wir haben hie (Stabil secle in terra noi non abbiamo) (10:40)

8 VII. Selig sind die Toten (Oh, beati i morti che muoiono nel Signore) (11:27)

Rosanna Carteri, soprano

Boris Christoff, bass

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York

*Hollywood Bowl Orchestra

**Rome Symphony Orchestra & Chorus of RAI

Bruno Walter, conductor

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

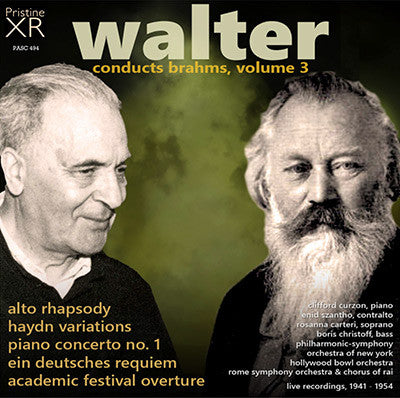

Cover artwork based on photographs of Walter & Brahms

*Haydn Variations: 10 July 1947

Alto Rhapsody: 9 November 1941

Piano Concerto No. 1: 28 January 1951

*Academic Festival Ov.: 10 July 1947

**German Requiem: 16 April, 1952

All performed at Carnegie Hall, New York

except *Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles, **Auditorium Rai di Torino

Total duration: 2hr 31:33

One emerges from the second concert of the Brahms series which Bruno

Walter is giving with the Philharmonic - Symphony Orchestra, which took

place last night in Carnegie Hall, with, if anything, an even deeper

impression of the music and its unique interpretation.

These

concerts apparently find Mr. Walter at the very zenith of his powers,

absorbed in a task which is especially dear to him. He conducted last

night the variations on the theme of Haydn, the Third Symphony, and the

First Piano Concerto, with the fortunate collaboration of Clifford

Curzon. He interpreted in such a manner that those who did not and will

not hear these performances are missing something the like of which they

are unlikely to hear again.

Mr. Walter was fortunate in his

pianist, for Mr. Curzon treated the piano part of the concerto with the

same sense of grandeur and poetry and passionate feeling entertained by

the conductor. In one respect Mr. Curzon was not fortunate. He came at

the end of a long and substantial program. This did not deter him from a

magnificent interpretation, in which he showed that while as a virtuoso

he had the music in the palm of his hand, he also had the complete and

sensitive understanding of the score which he would have manifested if

he had been conducting.

There was a further correspondence in the

complete unaffectedness and virility of his reading, and his ability to

capture mood and an introspective beauty of a rare kind in the passages

that contrast exquisitely with the prevailing ruggedness and grandeur.

There were salvos for the conductor and the soloist. This was

inevitable. One could only wish that the flying moment might have been

transfixed and preserved immaculate for the generations.

Olin Downes The New York Times, January 26, 1951 (excerpts)

Fanfare Review

The concerto recording is a true treasure. As usual, Pristine’s transfers are as good as it gets

The hugely important discovery here is the Piano Concerto No. 1 with Clifford Curzon, a New York Philharmonic concert in excellent monaural (and/or SR Stereo) sound from Pristine. This performance has never been available before. Curzon’s second studio recording for Decca, with George Szell has been a favorite of mine, and in fact I entered it into Fanfare’s Classical Hall of Fame in issue 15:5. That recording finds soloist and conductor each pulling the other toward a very happy middle ground that combines Curzon’s poetry, lyricism, and remarkable feel for color with Szell’s sense of architecture and rhythmic tension and release. His first studio recording, with van Beinum and the Concertgebouw, is also in the top tier, with a bit more dash and frisson than the Szell.

This live performance offers a conductor and soloist naturally attuned to each other, with some of the risk-taking that is only likely to occur in a live performance. There are moments of hushed dialogue in both the first and second movements (particularly the latter) that are pure magic. While I would not give away my Decca recording, neither will I give this one away. Olin Downes, in his New York Times review of the concert in 1951, said “… those who did not and will not hear these performances are missing something the like of which they are unlikely to hear again.” Now, thanks to Pristine, those of us who weren’t present can, in fact, have the experience. There seems an almost magical communication between pianist and conductor, in the way they shape phrases and scale dynamics. This is a true musical conversation.

The other special performance here is the 1947 Haydn Variations. Walter is often mis-characterized, particularly by those who prefer simplistic reductions rather than complex realities, as a gemütlich conductor whose principal performance style centers around a kind of generalized warmth. In fact, Walter was in no way one-dimensional. Yes, he did bring a kind of trademark lyricism to his work, but that should not be taken to imply a lack of rhythmic drive. This Haydn Variations performance (as with the last movement of the Piano Concerto) is marked by a fierce energy, and fully engaged playing by the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, although there are some shaky moments in terms of ensemble. Walter perfectly integrates the movements, with all their changes of tempo; the result is an organic, exciting performance that to my ears is an improvement over Walter’s Columbia studio recording.

Enid Szantho was a Hungarian contralto with a decent career, but there seems little that is special about her singing in the Alto Rhapsody. The Westminster Choir sings well enough, but frankly I see little reason to prefer this to Walter’s studio recording with Mildred Miller. The Academic Festival Overture, also recorded at the Hollywood Bowl in concert, is a wild ride—surprisingly unbuttoned and, at times, even uncontrolled. There are some ensemble problems here too, as in the Haydn Variations, but you can make the case that they add to the excitement, and we know that outdoor summer concerts have always been under-rehearsed.

The biggest puzzle to me is the German Requiem performance chosen here. I don’t know what alternatives were available to Pristine, but this Italian-language performance seems a very odd choice. The sound is quite good, and the performance is at 68:25 a full five minutes slower than the studio recording Walter made with Irmgard Seefried and George London. It is nice that Pristine gives us a good-sounding transfer, but I’m not sure the performance is one I will listen to more than once. The Italian language is odd in this music, the reading feels a bit cautious at times, and while the soloists have wonderful voices neither seems comfortable with the style of this music. The chorus sounds a bit raw at times too, less well blended than one would hope.

Despite reservations, though, Andrew Rose and Pristine deserve credit for increasing the available Bruno Walter material, since he was surely one of the major conductors of the first half of the 20th century. And the concerto recording is a true treasure. As usual, Pristine’s transfers are as good as it gets.

Henry Fogel