This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

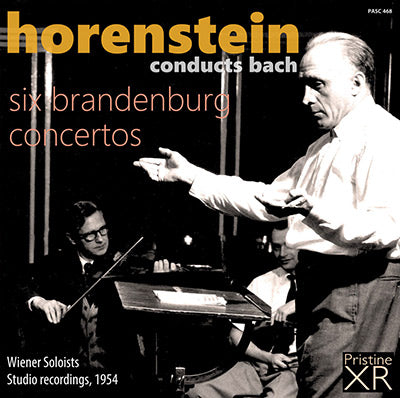

Horenstein's pioneering Period Instrument recording of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos

"You can’t go wrong with these Brandenburgs ... A must for Horenstein’s fans" - Fanfare

The release of this pioneering 1954 recording of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos has been brought forward to commemorate the life and work of the great conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1929-2016). In his notes for this release, Misha Horenstein observes the presence in the orchestra here of both Harnoncourt and Austrian composer and conductor Paul Angerer, suggesting: "It is not inconceivable that both these musicians, and some of the others, derived inspiration for the future direction of their careers from their work on this recording of the Brandenburgs."

This new XR remastering brings a greater sense of life, space and clarity to the recordings, as well as correcting for the first time a number of pitch issues present on the original tapes.

Andrew Rose

BACH Six Brandenburg Concertos, BWV.1046-51

Recorded in Vienna, 21-25 September 1954

Originally published on VOX DL122

Wiener Soloists

Jascha Horenstein, conductor

Walter Schneiderhan (solo violin)

Dimiter Tortscanoff (violin)

Paul Trimmel (violin)

Ernest Opawa (violin)

Rudolf Lindner (violin)

Paul Angerer (solo viola, violino piccolo, harpsichord, 2nd recorder)

Karl Troetzmueller (viola, 1st recorder)

Josef de Sardi (viola)

Viktor Goerlich (cello)

Nikolaus Harnoncourt (viola da gamba)

Hermann Hoebarth (viola da gamba)

Emil Kremer (contrabass)

Camille Wanausek (flute)

Friedrich Wachter (oboe)

Rudolf Spurny (oboe)

Josef Koblinger (oboe)

Leo Cermak (bassoon)

Franz Koch (horn)

Karl Buchmayr (horn)

Adolf Holler (trumpet)

Josef Ortner (trumpet)

Josef Nebois (continuo)

Notes on the recording

by Misha Horenstein

Nineteen fifty-four was a something of a moribund year for Horenstein in the concert hall. A tour of Latin America in February and March, followed by a few appearances in France between June and December constituted his entire workload for that year. Also unproductive were his attempts to secure full-time conducting positions in Berlin with the RIAS Orchestra and at the Städtische Oper, which fell on deaf ears. "I don’t have anyone in Berlin anymore who will take pains on one’s behalf", he complained, "and continually deal with the people who matter and suggest a name again and again." Closed doors also applied to his career, or lack of one, in the United States and in Britain, while the death of his close friend Karol Rathaus in November (followed nine days later by Furtwängler) shook him profoundly.

The situation was better in the recording studio. In June 1954 Horenstein was awarded the Grand Prix du Disque for his EMI recordings of Strauss's Metamorphosen and Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms (PASC 418 and 428), and in September he embarked on a further series of recordings for Vox Records in Paris, Bamberg and Vienna, all within the space of two months. Nestled between these was the present edition of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos, recorded in Vienna during the third week of September 1954.

Much better known for his performances of 19th and 20th century music, this recording represented an unusual change of direction for Horenstein. Its distinguishing feature is the use of period and modern instruments, one of the first recorded attempts to reproduce the original sound of Bach's orchestra in Cöthen and a precursor of what later became known as the 'Historically Informed Performance' movement that flourished in the late 1960s and beyond. Horenstein's thinking was way ahead of its time but it is unclear who or what influenced him to take up this experiment. It might have been Hindemith, whom he met in 1949, or T.W. Adorno, an old friend from the Weimar era, whose debates on the subject of authentic performances of baroque music during and after Bach's bicentenary year could have inspired him to adopt the idea.

Horenstein spent much time and effort searching for the right combination of period instruments, not as easy to find then as now, and auditioning the musicians to play them. In the end he settled for a twenty-two piece orchestra that featured a harpsichord, a violino piccolo, two recorders, two viole da gamba, two natural horns and a clarino trumpet in addition to modern instruments. This formation represented a revolutionary new approach to these masterpieces, which until then were usually performed in a romantic style, mostly by large orchestras with modern instruments, often with the keyboard part taken by a piano.

The players were drawn mainly from members of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra that included, most notably, the young Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Paul Angerer, both of whom later became important figures in the development of authentic performances of baroque and classical era music. It is not inconceivable that both these musicians, and some of the others, derived inspiration for the future direction of their careers from their work on this recording of the Brandenburgs.

The recordings were originally released in early 1955 on two extra-long-playing LPs in a deluxe, white ersatz-leather-bound edition (Vox DL 122). The package included a ninety-page booklet with detailed analytical notes, the complete score as well as a facsimile of Bach's flowery dedication as it appeared in the original manuscript, and was sold at a price lower than the three-disc competing versions. But despite their cost advantage, the luxury format and the acknowledged renown of the musicians who took part, contemporary reviews were unusually negative. "The Vox ensemble under Horenstein", complained a clearly irritated Andrew Porter in The Gramophone, "merely plod along through yet another set of Brandenburgs". Republished a number of times since their first appearance, subsequent critical evaluation has been far more charitable.

As one of the first examples of its kind there can be little doubt that this recording contributed to the birth of the authentic performance movement, even though it was primarily the composition of the orchestra and some surprisingly nimble choices of tempo (for that time), and less the technical and stylistic aspects of Horenstein's interpretations, that faithfully reproduced the Baroque sound. However, his subsequent use of smaller ensembles and his preference for lighter textures in performances of classical and early romantic music, as evidenced by his second reading of Beethoven's Eroica and other recordings for Vox, appear to have been stimulated by his work on the Brandenburgs.

Reviews: MusicWeb International & Fanfare

Horenstein's well executed and sometimes exciting performances

Here’s a reissue of a 1954 monaural recording from the Vox label. The accompanying booklet, if you can call it that—it’s printed on one side of a single sheet—has only of a list of performers (apparently a pick-up group), a brief producer’s note, and a concise Fanfare review, not by me, from 1996. We occasionally stick multiple reviewers on a new release, and I’ve seen blurbs in a booklet, but this is a first in my experience. What to do?

Well, I’m in general agreement with the observations of my colleague, Richard Burke. He pointed out that Vox’s claim that it was the first “original-instruments” Brandenburg set is not quite accurate. The “Wiener Soloists” did use a violino piccolo, recorders, and violas da gamba, but modern instruments otherwise. I agree that Jascha Horenstein’s tempos were, for the time, “startlingly up-to-date,” though I’m a little less convinced that the “slow movements never drag.” Burke’s assertion that “these are performances of great distinction” may be a little overstated—I’d be inclined to drop the “great”—but these are nonetheless performances of interest, and it’s good that they’ve been preserved. They are “certainly not,” in Burke’s estimation, “a first or second choice” for a Brandenburg set, but I agree with him that they are certainly worth hearing.

The producer’s note states that this set was revived to honor the late Nikolaus Harnoncourt. And, indeed, Harnoncourt did participate in Concerto No. 6, playing the viola da gamba part presumably written for the limited abilities of Prince Leopold of Cöthen. More noteworthy was the remarkable versatility of the Swiss composer and conductor Paul Angerer, who played solo violin, violino piccolo, harpsichord, and recorder in the sessions. Mysteriously, two trumpet players are listed in the roster of players. What was that all about?

Summing up: You can’t go wrong with these Brandenburgs, but you can do better. A must for Horenstein’s fans. Decent monaural sound.

George Chien

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:1 (Sept/Oct 2016) of Fanfare Magazine.

A typical performance of the

Brandenburg Concertos given in 1954, the year of this recording, might

have used a sub-set of a modern instrument symphony orchestra, augmented

by a harpsichord.

Horenstein, however, assembled a group of

twenty-two players and used a mix of modern and period instruments.

Among the latter are a violino piccolo, violas da gamba, recorders and a

harpsichord. The other winds and strings are modern instruments.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Paul Angerer (both to become conductors and,

in Angerer's case, also a composer) are among the players.

As a

comparison, I listened to a Philips recording made by Neville Marriner

and the Academy of Saint Martin's in the Fields in 1980 (their second

recording of these works). Marriner, like Horenstein, uses a

combination of modern and period instruments, many played by

distinguished guest artists including Jean Paul Rampal, Carl Pini, and

Henryk Szeryng.

Most of Marriner's tempos are faster than

Horenstein's, but not by huge margins, and there are a few movements

where Horenstein's are swifter. I infer from this that Horenstein's

speeds are fast for their time. The playing in both sets is alert and

polished.

Horenstein's sound is bright, full and clear, with

the horns excitingly forward in the First Concerto. The strings, as the

accompanying notes acknowledge, have an 'edge' and this adds a touch of

astringency which devotees of 'historically informed' performances may

enjoy, but which others may tire of, if too much is heard at one

sitting. It's better, perhaps, to hear each disc at a separate

listening session.

Marriner's Philips sound is more refined,

marginally warmer and has the benefit of stereo engineering. His horns

in the First Concerto are more recessed, but still satisfying. An

oddity in his set is the addition of a middle movement in the Third

Concerto. Officially, the work has only two movements and, according to

the Oxford Dictionary of Music, this has led to much

speculation by scholars concerning the 'missing' movement. Marriner has

'solved' this problem by inserting a brief Adagio identified by

Philips simply as 'BVW 1019a'. Investigation shows this to be part of

the first version of the Sonata for violin and keyboard No. 6 in G

Major. It sounds quite effective in the concerto.

It is in the

Sixth Concerto that the two conductors differ most in their approach

(specifically in the last two movements). The Second Movement is

marked Adagio ma non tanto ('Slow but not too much'). Horenstein

ignores the qualifier and directs a leisurely, 'heavenly' Adagio. He

follows this without pause with a swift and energetic Final Movement

Allegro. This slightly unorthodox approach provides a contrast between

the two movements which is extremely exciting. It is a master stroke by

a master conductor.

Marriner obeys the tempo marking of the

Second Movement and 'pushes' it slightly, without losing all repose.

His following Allegro is comparatively leisurely with the result that

there is less contrast between the movements and less excitement than

Horenstein finds.

I rounded off my Brandenburg Concerto

listening sessions with some extracts from a period instrument set

performed by the Dunedin Consort conducted by John Butt and released on

Linn Records. The Consort has ten musicians, one to a part, with Butt

conducting from the harpsichord. As reported in Kirk McElhearn’s review

of this set, the pitch is a low 392 Hz and Butt is quoted as saying

that this ‘brings a warmth and glow to the sound’ which ‘tends to

encourage a slightly slower but more subtle articulation for most

instruments’.

I did find these qualities of warmth and subtlety

in the extracts I heard and, whilst these are unmistakably

‘historically informed’ performances, my ears weren’t taxed in a way

they might have been by a colder and more relentless approach. In the

Sixth Concerto, Butt doesn’t make the dramatic contrast Horenstein did

between the last two movements, but in the Slow Movement he is more

relaxed than Marriner and faster than him in the Finale. The set has

received enthusiastic reviews.

In sum, Horenstein's well

executed and sometimes exciting performances can be regarded as advanced

for their time, a kind of 'half-way house' between the traditional

approach to these works and modern renditions. Making due allowance for

their relatively unrefined string sound, they would make a worthwhile

supplement to much more recent recordings Bach lovers might have in

their collections.

Rob W McKenzie

MusicWeb International