- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

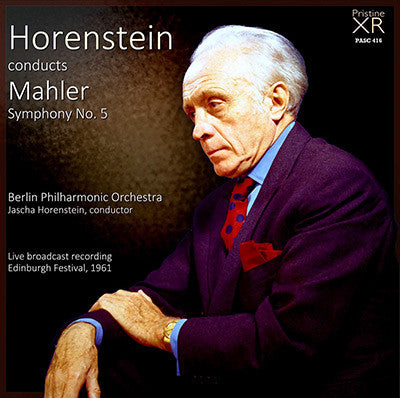

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

Jascha Horenstein in electrifying form in this 1961 Mahler 5th with the Berlin Philharmonic

Elusive recording finally transferred and XR remastered from off-air broadcast recording

I was contacted earlier this year by Misha Horenstein, cousin of the

great conductor, with the idea of remastering and releasing rare and

special recordings from the Maestro's career. The Mahler Fifth was the

most notable gap in Horenstein's extensive recorded legacy and this

off-air recording of a blazing Edinburgh Festival concert with the

Berlin Philharmonic was regarded as by far the most promising place to

start a new Horenstein series at

I've pulled out all the stops to try and bring out as much of the passion and brilliance of the performance as remains in the recording, whilst eliminating or reducing crosstalk, interference, a good deal of hiss, swish and other defects. A very short sequence towards the end of the piece was missing from the original source, and here we've patched in one of the other Horenstein recordings, matched as closely as possible to this in order to maintain the musical flow.

- MAHLER Symphony No. 5

Recorded Edinburgh Festival, 31 August, 1961

Usher Hall, Edinburgh, Scotland

Live broadcast recording

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Jascha Horenstein - conductor

Jascha Horenstein's Mahler 5

For many years it was assumed that no recordings existed of Horenstein conducting Mahler's Fifth Symphony, but in the last few years no less than three have surfaced: with the London Symphony Orchestra, the Goteborg Symphony Orchestra, and this one with the Berlin Philharmonic, recorded live during the 1961 Edinburgh Festival.

Horenstein first conducted Mahler's Fifth in Berlin in 1927 with the Berlin Philharmonic. That concert brought him his first really big success as a young conductor, with extremely favorable reviews from highly respected musicians and critics such as Walter Schrenk ("Horenstein is the most significant and by far the most gifted of our young generation of conductors"), Klaus Pringsheim, formerly an assistant of Mahler's ("he reminds one of the young Klemperer who, it is said, reminded his audiences of the young Mahler"), and Rudolf Kastner, who had attended the world premiere of the Fifth Symphony conducted by Mahler in 1904 ("Since then I have rarely heard the piece as I did now… Horenstein is one of the most remarkable conductors we have encountered in recent years and has, like few others, a most particular affinity for Mahler’s music"). It was this concert that secured Horenstein's reputation as one of the finest interpreters of Mahler's music by a new generation of conductors that had no personal contact with the composer, and it must have been with these memories in mind that he approached the performance in Edinburgh presented here.

Of the three extant recordings of the symphony conducted by Horenstein, the Berlin Philharmonic performance is by far the most dramatic, a white-hot, tension-filled, powerfully driven presentation that confirms Horenstein's widely recognized and unrivaled authority in this repertoire.

Misha Horenstein

Pristine's Review

Hall of Fame Review

Great conductors surpass talented conductors, yet on occasion they also surpass themselves. This live Mahler Fifth from the Edinburgh Festival in 1961 feels like one of the greatest nights in Horenstein’s life. It’s certainly one of the greatest nights in the life of this symphony. He takes the music into regions where today’s standardized Mahler never dares to go. In the uncanny way that born conductors can make inspiration flow directly from the baton, here even the bare opening trumpet call portends something very special.

Horenstein achieved one of his earliest successes conducting the Mahler Fifth in 1927 with the Berliners, and one wonders what his career arc would have been like without the disastrous intervention of Nazism. In the postwar era he wasn’t one of the luckiest émigré conductors—he found himself lionized as a cult figure but otherwise saddled with second- and third-rate orchestras far too often. His real stature was just beginning to be recognized on a wider scale when he died in 1973, just shy of his 75th birthday. The scarcity of recordings with a top orchestra made it seem that a famous one like his Mahler Third with the London Symphony might almost be a one-off. Fortunately, when the BBC Legends label began to unearth an abundance of live recordings, the real story began to jell—no conductor has benefitted more from posthumous concert releases than Horenstein.

Yet even by this measure, the Edinburgh Mahler Fifth (one of three different accounts that have been discovered in recent years) is extraordinary. It bursts three myths in one go: the myth that Horenstein was careless about orchestral execution, that top European orchestras had all but forgotten him, and that the Berlin Philharmonic in the Karajan era knew almost nothing about playing Mahler. In a recent Fanfare review, Jim Svejda says, quite rightly, “What will initially amaze you is the extent to which the orchestra plays the Mahler Fifth as though it were an item from the standard repertoire, which of course it most certainly was not in 1961. The playing is shot through with a bracing confidence and élan.”

Together, Svejda and Henry Fogel have praised this release (in issue 38:2) with such well considered judgment that I can offer only a footnote and a rousing cheer of agreement. For intensity, originality, deep understanding, and comprehensive sweep, Horenstein’s Edinburgh Mahler Fifth is one for the ages.

Huntley Dent

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:4 (Mar/Apr 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.

To call this a release of enormous importance is to understate the case. Collectors know Horenstein as one of the great Mahler conductors of the 20th century, but one who lacked big-label recording contracts. He made a few extraordinary commercial studio recordings of Mahler, including superior stereo recordings of Nos. 1, 3, and 4 along with some scrappy monaural efforts for Vox. The rest of his Mahler, like this, comes from broadcasts of live performances. Until now we have been missing a Fifth and a Second. Let’s hope there is a Second out there somewhere to complete the cycle, but at least we now have the Fifth.

And what a performance this is! Working with one of the world’s great orchestras, at the Edinburgh Festival, Horenstein fashions a reading of extraordinary drama and range. What has always distinguished his Mahler conducting was that, unlike most, he found a way to encompass the huge scope and variety of Mahler’s musical imagination into one unified performance. Horenstein brings lyrical beauty and richness, rhythmic tension and snap, and extreme contrasts of tempo and dynamics. Moreover, he is a master of Mahler’s almost schizophrenic melding of the sublime and the vulgar, the mystical and the anguished. Most Mahler performances concentrate on one or another aspect of Mahler’s complex, multi-faceted world. Horenstein manages to encompass it all.

What makes Mahler’s music a feasting ground is its emotional range, giving conductors an ability to wallow in any particular one of the emotional worlds the music inhabits, and a justification for doing so. And performances can be enormously satisfying while focusing on the Angst, or the sublime beauty, the love of nature, the hedonism, or the vulgarity, or even the rage that can be found in the scores. What makes Horenstein unique is that he balances all of those elements more evenly than virtually anyone, and does so without seeming calculation or reticence. He is clearly involved and at home in all of Mahler’s crazy world, not just parts of it. He goes deeply into the music; for instance, we never forget in this performance that the first movement is a funeral march. We hear that from the opening trumpet call, which has a remarkable gravitas about it, a mood that continues throughout the movement, but miraculously with no loss of momentum or urgency.

One of the impressive aspects of Horenstein’s conducting, in Mahler and in other composers, is his careful attention to balances. In Mahler’s complex scores, there are many musical incidents going on simultaneously, and the music requires an ear for balance and texture that allows everything to be heard in the correct proportion, without the clarity minimizing the cumulative impact. In this performance, even big climaxes are crystal clear (despite the sonic limitations of the recording); we discern multiple voices and still feel the impact of the whole.

Recordings in my collection range from approximately 67:00 to 76:00; at 74:37 Horenstein falls on the slow end (the 75:52 listed in the headnote includes 1:15 of applause). But nowhere does the performance feel slow, because of the sharp rhythmic contours and the sense that it is always headed somewhere, and because there is a far greater variety of tempo than there is in most performances. There are sections that, if you compared them to Kondrashin or Walter (the two fastest conductors in my library), Horenstein would seem quite similar. There are other sections where he may even be slower than Tennstedt or Barbirolli. What is most remarkable, however, is his ability to stitch those extremes together into a unified whole with real shape to it. Often performances with such great extremes of tempo lose the overall arch of the music, but not here. A good part of his success is the smooth and perfectly judged tempo changes that he manages.

Another strength of the performance is the beauty of the string playing, and the richness of color and texture that he gets from the Berlin Philharmonic. This is no accident; all one needs to do is listen to the last movement of his LSO recording of the Mahler Third Symphony to appreciate fully Horenstein’s ability to draw string playing of great beauty from an ensemble. In the famed Adagietto, this quality is wrenchingly beautiful, and it echoes in the mind’s ear long into the rambunctious finale. Despite the richness and variety of string sound, and the slow tempo for the Adagietto, Horenstein’s performance comes across as tender and to some degree restrained, rather than the kind of urgent cry from the heart that it can be with, for example, Bernstein. I don’t believe any one approach is more right than the other; both are valid explorations of Mahler’s immense and multi-faceted world. Part of Horenstein’s success is the very wide dynamic range he employs, with many gradations between pianissimo and fortissimo. Horenstein also employs, tastefully, portamento effects, strings sliding from one note to the next. That was a common feature of orchestral (and solo) string playing in the early 20th century, and is singularly appropriate to Mahler. That is one of the reasons for the great success of his recording of the Third Symphony, and so it is here.

Some might find Horenstein’s finale a bit too slow for their taste. As one starts to listen to it, one wants to move it ahead a bit. However, it fits his overall conception and, despite the tempo and the weight, it never loses its momentum. This music has a relationship with Wagner’s Die Meistersinger, and one senses that here more than in many performances.

The Berlin Philharmonic players give the conductor their all. This must have been one of the BPO’s earlier Mahler performances, but they play it with conviction. The recorded sound is somewhat gritty and compressed, but more than listenable to anyone who is used to historic recordings. I listened to the XR stereo version, which is Pristine’s attempt to capture some sense of space and ambience; it succeeded in doing that.

Henry Fogel

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:2 (Nov/Dec 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.

Among those with a passion for Mahler symphonies it would be difficult to overstate the importance of this recording. After the version of this very work that Bruno Walter recorded with the New York Philharmonic in 1947, the first great Mahler recordings of the post-War era were those of the First and Ninth symphonies that Jascha Horenstein made in 1953 with the decidedly low-powered Vienna Symphony (still available on Vox 5508). Subsequent, sonically superior studio recordings of the First and Third—together with various live versions of several of the others—only confirmed what those early recordings clearly implied, that Jascha Horenstein was one of the most potent and individual Mahler conductors that history has known.

Recorded live at the 1961 Edinburgh Festival—well before it became all but overshadowed by the annoying, pathologically trendy Fringe—this Berlin Philharmonic performance is one of three Horenstein Mahler Fifths that have recently surfaced and is, according to the note the conductor’s nephew Misha supplied for its first CD appearance “by far the most dramatic, a white-hot, tension-filled, powerfully driven performance.” While it’s certainly all of that, it’s also a good deal more.

What will initially amaze you is the extent to which the orchestra plays the Mahler Fifth as though it were an item from the standard repertoire, which of course it most certainly was not in 1961. The playing is shot through with a bracing confidence and élan—listen, for instance, to the swaggering horns and the beginning and end of the scherzo: If they don’t raise the goose bumps (or the blood pressure), you might want to call your endocrinologist in the morning—and in fact from first to last the performance sounds much more “lived in” than the self-conscious, smooth-shod monstrosity Karajan made of the piece a dozen years later with the same orchestra.

But along with the intensity that Mischa Horenstein notes comes a refinement and sensitivity that are even more striking. In the scherzo’s trio, the phrasing has an aching delicacy that few others can muster, while the final movement ambles along with such witty nonchalance that for once it never threatens to become the head-long horserace it so often is. (In his famous EMI recording, John Barbirolli also proved that speed and excitement aren’t always the same thing.) The Adagietto not only unfolds with a completely unforced ease but it also seems to do so in a single, unbroken phrase (a reminder perhaps that Horenstein, in his youth, served as an assistant to Wilhelm Furtwängler).

Needless to say, the off-the-air recorded sound is hardly state-of-the-art, though the ear quickly adjusts. And if Bernstein (DG), Tennstedt, Kubelík, Gary Bertini, the recent Iván Fischer and the aforementioned Barbirolli remain the top choices for modern Mahler Fifths, as an historic, human, and musical document, this one can’t be missed.

Jim Svejda

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:2 (Nov/Dec 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.