This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Additional notes

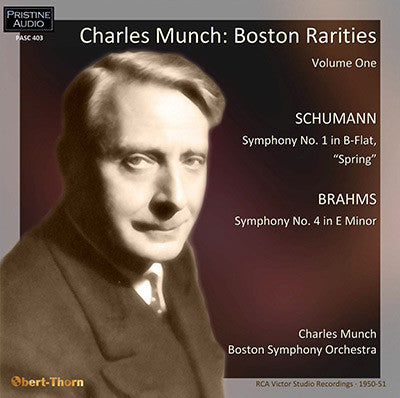

Rare and long out-of-print recordings by Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra

First CD outing for these major symphonic works in new Obert-Thorn transfers

This release is the first of two which focus on Munch/Boston studio recordings that have never seen an “official” CD reissue, not even in the 40-CD (plus one bonus CD) Japanese RCA series, “The Art of Charles Munch”. The present program features two symphonies recorded early in Munch’s Boston tenure. One distinguishing characteristic of the Schumann is that the first and fourth movement repeats are observed on this recording, while they are cut in Munch’s 1959 stereo remake.

The original LPs were burdened with a rather uningratiating sound (surprisingly from the same Richard Mohr/Lewis Layton team which would go on to produce so many excellent “Living Stereo” releases) – over-reverberant and limiter-plagued. This was a conscious choice in RCA’s engineering from the mid-1940s through the early ‘50s to suggest, as one modern critic put it, a sound so huge, it could scarcely be contained by the microphones. Adding insult to injury, the original LP issue of the Schumann was pitched a semitone sharp, and the first movement contained several minor but noticeable pitch drops. These have been corrected in the current release.

Mark Obert-Thorn

SCHUMANN Symphony No. 1 in B-flat major, Op. 38, “Spring”

Recorded 25 April 1951 in Symphony Hall, Boston

First issued on RCA Victor LM-1190

BRAHMS Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98

Recorded 10 - 11 April 1950 in Symphony Hall, Boston

First issued on RCA Victor LM-1086

Boston Symphony Orchestra · Charles Munch

Munch made his début with the Boston Symphony Orchestra on 27 December 1946. He was its Music Director from 1949 to 1962. Munch was also Director of the Berkshire Music Festival and Berkshire Music Center (Tanglewood) from 1951 through 1962. He led relaxed rehearsals which orchestra members appreciated after the authoritarian Serge Koussevitzky. Munch also received honorary degrees from Boston College, Boston University, Brandeis University, Harvard University, and the New England Conservatory of Music.

He excelled in the modern French repertoire, especially Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, and was considered to be an authoritative performer of Hector Berlioz. However, Munch's programs also regularly featured works by composers such as Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, and Wagner. His thirteen-year tenure in Boston included 39 world premieres and 58 American first performances, and offered audiences 168 contemporary works. Fourteen of these premieres were works commissioned by the Boston Symphony and the Koussevitzky Music Foundation to celebrate the Orchestra's 75th Anniversary in 1956. (A 15th commission was never completed.)

Munch invited former Boston Symphony music director Pierre Monteux to guest conduct, record, and tour with the orchestra after an absence of more than 25 years. Under Munch, guest conductors became an integral part of the Boston Symphony's programming, both in Boston and at Tanglewood.

Munch led the Boston Symphony on its first transcontinental tour of the United States in 1953. He became the first conductor to take them on tour overseas: Europe in 1952 and 1956, and East Asia and Australia in 1960. During the 1956 tour, the Boston Symphony was the first American orchestra to perform in the Soviet Union.

The Boston Symphony under Munch made a series of recordings for RCA Victor from 1949 to 1953 in monaural sound and from 1954 to 1962 in both monaural and stereophonic versions.

Selections from Boston Symphony rehearsals under Leonard Bernstein, Koussevitzky, and Munch were broadcast nationally on the NBC Radio Network from 1948-1951. NBC carried portions of the Orchestra's performances from 1955-1957. Beginning in 1951, the BSO was broadcast over local radio stations in the Boston area. Starting in 1957, Boston Symphony performances under Munch and guest conductors were disseminated regionally, nationally, and internationally through the Boston Symphony Transcription Trust. And, under Munch, the Boston Symphony first appeared on television.

Wikipedia

Fanfare Review

Vive le beau Charles!

These are great performances, available for the first time on CD. Why should one get monaural recordings of works Munch and the BSO re-recorded in stereo? First, as producer Mark Obert-Thorn notes, the present version of the Schumann includes repeats in the first and fourth movements that Munch omitted in his 1959 remake. The repeats contribute to the majesty and depth of Munch’s overall conception. Second, Munch rarely gave the same interpretation of a work in repeat performances. He was a highly improvisational artist, which in part accounted for his relaxed attitude toward rehearsals. Michael Steinberg, the BSO’s longtime program annotator, wrote that Munch was “short on discipline and sheer industry,” but I think he just saw no need to imprint one specific performance on the orchestra during rehearsal. My high school music teacher said that Munch was “too nice a guy,” yet if you take him in total you appreciate the results that he got. As with Karajan and Giulini, Munch’s handsome features gave him an advantage in drawing a beautiful sound out of an orchestra. As an older woman I know said to me of Munch, “I thought he looked like God.” Certainly the performances on the present CD are filled with electricity and sheer sonic beauty. Martin Bookspan wrote that Munch had a tendency to “freeze up” in the recording studio, but that’s not the case here. A BSO player commenting on the succession of Erich Leinsdorf to Munch as music director said, “The highs were not as high, but the lows were not as low.” Luckily we have two instances here of “the highs.”

In the “Spring” Symphony, the introduction of the opening movement is like the unraveling of some cosmic matter, a sort of Maestoso churning of the heavens. The movement’s main section is loaded with charm, as all nature comes to life. The BSO players are on the edge of their seats. The Larghetto presents a pastoral idyll, with the sun and clouds shifting through the trees. A peasant feeling dominates the scherzo, mixing together song and dance. The final movement’s high spirits almost sound a bit tipsy, as if Schumann were translating his heavy drinking into sound. This surely is one of the great statements of this symphony. In the Brahms Fourth, one notes Munch’s admiration for Toscanini. There is the same quickness in tempo and clarity of texture, although Munch draws a more beautiful sound out of the BSO than Toscanini did from the NBC. At no point do we encounter the Central European indulgence in phrasing and plushness of sound that one hears, say, from Wolfgang Sawallisch and the London Philharmonic. Munch’s opening movement is direct and unaffected. The severity of its rhetoric is offset by a bucolic feeling in the winds. His slow movement sounds like a dramatic soliloquy, Shakespearean in its sense of self-revelation. The third movement is positively Jovian, having an Olympian jocosity. For the last movement, Munch takes the direction “with energy and passion” very much to heart. To Munch, there’s an inevitability to this last symphonic movement by Brahms—nothing could follow it. I’m not sure I always would want to hear the Brahms Fourth this way, but when I’m in the mood it’s fantastic.

The sound engineering is full and probably too reverberant, although the Brahms is a little closer up than the Schumann. Obert-Thorn has opted to leave in a lot of tape hiss, which in all likelihood does the tone color some good. My favorite stereo version of the Schumann is the period performance informed account by Florian Merz conducting the Klassische Philharmonie Düsseldorf. For a traditional rendition, I like Christoph Eschenbach with the Bamberg Symphony; I have not heard his Hamburg remake. The best stereo Brahms Fourth I know is Antal Doráti’s with the London Symphony. Charles Munch’s recordings were an integral part of my upbringing, so encountering the present reissue was like meeting again a treasured and admired friend. All I can say about this CD is Vive le beau Charles!

Dave Saemann

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:1 (Sept/Oct 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.