This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

Early electrical recordings from WH Squire - one of the first "serious" musicians ever to record

"There is in this recording some excellent orchestral tone, and the ’cello comes off very well" - The Gramophone, 1930

Cellist, composer and pedagogue William Henry Squire was born in Herefordshire in 1871. He studied at the Royal College of Music in London and with Carlo Alfredo Piatti, making his debut in 1891. He played as principal cellist in several London orchestras in addition to his solo career and composed many short works.

Squire’s discography extends back to the very beginnings of the recording industry in Britain. He cut his first sides for the Gramophone Company in London in 1898, becoming the first instrumentalist of repute to embrace the new medium. Throughout the Teens and Twenties, he was a mainstay of the Columbia catalog, recording many short works (often accompanied at the piano by Hamilton Harty) as well as chamber music.

In 1926, he made Columbia’s first concerto recording using the new electrical process, the Saint-Saëns presented here. This and the Elgar were to be his only concertos on disc. Although a 1931 session produced two sides, they remain unreleased. The Bach and Popper selections from 1929 are his last issued recordings, even though he continued to perform publicly until 1941. He died in 1963 at the age of 91.

Collectors familiar with Squire’s Saint-Saëns concerto set know it as the one with “all bass and no top”, at least when played back using a recording curve typical of the period. By transferring it with a flat equalization and building up the frequency emphases from the bottom up, however, I have been able to get a more natural result, although the sound is still not state-of-the-art, even for its time.

By contrast, the original engineering of the Elgar concerto is superb for its date, sounding like recordings made several years later. I was helped in its transfer by the use of first-edition white label English Columbia test pressings, whose presence and detail eclipsed even the fine American Columbia “Full-Range” copy with which I compared it. An American Columbia “Viva-Tonal” set was used for the Saint-Saëns concerto, while the solo sides with piano came from early English pressings and the two sides with organ from a mid-1930s American edition.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

SAINT-SAËNS: Cello Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 33

Hallé Orchestra/Sir Hamilton Harty

Recorded 25 March 1926 in the Columbia Studios, Petty France, London

Matrix nos.: WAX 1414-2, 1415-1, 1416-1, 1417-1, 1418-4 and 1419-1

First issued on Columbia L 1800/02

-

GODARD: Berceuse from Jocelyn

Recorded 9 March 1928 in London · Matrix no.: WAX 3349-1 · Columbia L 2126

-

SAINT-SAËNS: The Swan from Carnival of the Animals

Recorded 9 March 1928 in London · Matrix no.: WAX 3350-1 · Columbia L 2126

-

DUNKLER (arr. Squire): Humoresque (Chanson à boire)

Recorded 9 March 1928 in London · Matrix no.: WAX 3354-2 · Columbia L 2128

-

HANDEL: Largo from Xerxes

Recorded 9 March 1928 in London · Matrix no.: WAX 3355-2 · Columbia L 2128

-

WAGNER (arr. Squire): Prize Song from Die Meistersinger

George Thomas Pattman (organ)

Recorded 3 October 1928 in the St. John’s Wood Synagogue, London

Matrix no.: WAX 4125-2 · Columbia L 2186

-

MOZART (arr. Squire): Ave verum corpus, K.618

George Thomas Pattman (organ)

Recorded 3 October 1928 in the St. John’s Wood Synagogue, London

Matrix no.: WAX 4126-1 · Columbia L 2256

-

BACH (arr. Squire): Air from Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D major, BWV 1068

Recorded 2 November 1929 in Central Hall, Westminster

Matrix no.: WAX 5251 · Columbia LX 23

-

POPPER: Tarantelle

Recorded 2 November 1929 in Central Hall, Westminster

Matrix no.: WAX 5252-1 · Columbia L 2371

-

ELGAR: Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85

Hallé Orchestra/Sir Hamilton Harty

Recorded 30 November 1928 in Free Trade Hall, Manchester

Matrix nos.: WAX 4410-1, 4411-1, 4412-1, 4413-3, 4414-1, 4415-1, 4416-1 and 4417-2

First issued on Columbia DX 117/9

W. H. Squire (cello)

(Tracks 4 – 7, 10 and 11 with piano accompaniment, uncredited)

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

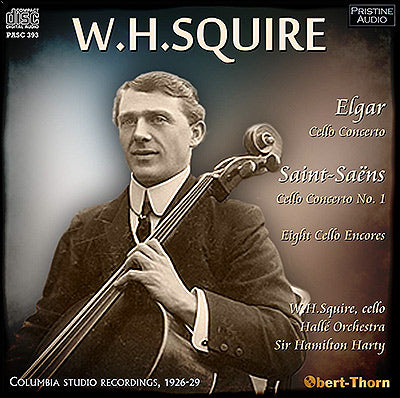

Cover artwork based on a photograph of W. H. Squire

Special thanks to Nathan Brown, Charles Niss and Jon Samuels for providing source material

Additional pitch stabilisation: Andrew Rose

Total duration: 77:11

REVIEW - ELGAR Cello Concerto

The

early recording of the Elgar concerto was by Miss Harrison, the L.S.O.

being conducted by the composer (H.M.V.). This was got on to three

discs. For this cheap album edition we are grateful. Eleven years ago

the work disappointed some, but only, I think, because it was so

different from other concertos. It comes from Elgar’s late chamber music

period, and has some of the chamber music way of thought. Mr. Squire is

not quite my ideal in capturing the spiritual qualities of the music.

The recording is loud, firm, solid, and the soloist comes out too much,

in the older concerto way, instead of blending with the orchestra in a

way that so finely distinguishes the best performance of the music. I

remember the 1919 début, when

Mr. Salmond had a hard time of it with the band, yet won for the work

the acknowledgment that it was something to live with and learn—learn,

maybe, that the riches of concerto form are not yet exhausted, while we

have a supreme master to mould the form anew and breathe into it his own

fresh imaginative life. There is in this recording some excellent

orchestral tone, and the ’cello comes off very well in a broad way ; but

Mr. Squire’s way of life is not Elgar’s ; he does not seem to me to get

below the surface ; and without that one might easily know little of

the riches to be mined there. To use a word-play, they are mind-riches

indeed—mind and heart marvellously combining to fuse them into rare

metal. I am glad to praise such parts of the performance as allow the

more obvious ’cello activities to shine, as on side three. Mr. Squire’s

tendency to uso portamento freely is again in evidence. Portamento

is the ’cellist’s dangerous friend ; and it may easily become cheap. We

sympathise with his long journeys on those strings ! A friend who puts a

head in at the door at this moment, when the big sweeping tune is going

off (end of side three), says, rather unkindly, one word : “Coliseum” ;

but adds in qualification “But that tune does ask for it a bit, doesn’t

it?” I agree : but there’s everything in the way you grant what is

asked. In a word, this is a work demanding subtlety, refinement, variety

of tone (in which Mr. Squire is not notably rich), possibly oven a

Puckish spirit, with a dash of Gerontius,

and, very strikingly, the partnership sense with the orchestra (whose

part, by the way, may easily be under-estimated, for it is often slight

in texture). It needs, too, a bit of the demonic—a kind of sublimated

demon, if you see what I mean—a spiritualised, but, as it were,

electrified demon - rarefied and yet not thin or stalky. Elgar, in this

work, goes further than usual outside his most readily label-able

qualities, yet the result does not cease to be Elgar in every bar. As I

read what I have just written, I doubt whether I have given up truly

what I feel in my bones. Mostly one can, by pausing and searching for

words, get somewhere near that; but I feel a difficulty in describing

this concerto, and am very anxious that those who do not happen to have

heard it performed several times should not think less highly of it

than, I am persuaded, it deserves. So if you have not the H.M.V. (which I

am compelled to count a good deal better than this), by all means

speculate eighteen shillings. If you can also hear someone like Miss

Harrison (possibly inclined to over-sentimentalise it, I think) or Mr.

Salmond, do so. I wish there were more ’cellists who would play the

work. Tertis has arranged it for viola, but some of its special flavour

departs then. Don’t give it up as unsatisfactory. I might perhaps add

that it is easy enough to follow. The danger lies, I think, in possibly

thinking that its slightness of texture, and its difference from

show-concertos, mean that it lacks interest or power. It is a work about

which I should particularly like to have the opinions of music lovers

of all kinds. Perhaps some representative members, say, of the N.G.S.,

will drop the Editor a word about it?

W. R. Anderson. The Gramophone, November 1930

Review of Columbia DX.117-20

Fanfare Review

The most important things here are the concertos, revealing documents both of Squire’s art and ones preserving a little slice of gramophonic history.

W.H. Squire (1871-1963) was one of the first prominent cellists to

record. In fact his career in the studios dates back as far as 1898.

Many a collector will wistfully recall the label rubric; ‘’cello

obbligato by W.H. Squire’ - not least collectors of the recordings of

Clara Butt, who was just one of the formidable singers to whom he lent

his art on disc, in recital and at the vast Royal Albert Hall, where he

was frequently to be heard.

William Henry Squire is an interesting case as a musician. His early

recordings, those made around the turn of the century and after, show a

man still in thrall to his teachers Edward Howell and Piatti - he’d also

studied composition with Parry and was a noted ballad composer - but

gradually exposure to the new wave of cello tonalists, principally

Casals, led to greater vibrato usage. His early quite sparing use of the

device was to be replaced over time by a prominent and constant, if

often quite slow, use of it. The curve of his recordings, from 1898 to

1929, is a fascinating study in changes of technical and expressive

devices, all faithfully reflected by the fledgling recording industry.

He first recorded for HMV but by the period covered in this disc he had

signed to Columbia. In 1926 he set down Columbia’s first electrically

recorded concerto disc, Saint-Saëns’s A minor concerto with the Hallé

Orchestra and its conductor, Squire’s old friend, Hamilton Harty. The

Mancunian band decamped to Columbia’s so-so Petty France studios in

London for a recording transfer engineer Mark Obert-Thorn rightly

describes as ‘all bass and no top’. In addition to being the first

electrical concerto recording, this was the first time the concerto had

been recorded. Squire had first performed it - a work that had been

composed the year after his birth - in 1894 with August Manns

conducting. The most obvious thing to note in his playing here is the

complex web of insistent portamenti allied to an extremely elasticised

sense of legato. It gives the music-making a very personal stamp. The

nature of his own playing contrasts too with the tonal qualities of the

wind principals, who retain their very bleached, white vibrato-free

tones, ones yet to have been influenced by slightly later British

avant-garde players (in their own way) such as Leon Goossens, Alec

Whittaker, Jack Thurston and Reginald Kell. This all makes for

fascinating conjunctions of style and tone. Squire is at his most

expressive and supple in the finale - fine bowing, good range of tone

colour, excellent characterisation. There’s not the sheer athleticism of

the generation of cellists to come and no doubt the performance would

have seemed very old style in the days of Piatigorsky, Fournier, Navarra

and Nelsova. Nevertheless the set remained in the domestic catalogue

until as late as 1940.

As for the transfer, Obert-Thorn has done a thoroughly recommendable

job. The only other transfer known to me was on a Past Masters LP

[PM15]. It compounded the stygian nature of the original recording by

cutting surface noise to such an extent that the result was a very

tricky listen indeed. Here much more noise has been retained and some

tweaking of the frequencies ensures that, whilst by no means perfect,

things are very different indeed.

The companion concerto is the Elgar, recorded in 1928 this time in the

Free Trade Hall, Manchester. Squire had first met Harty in 1901 in the

Rotunda, Dublin where Harty astonished the cellist by sight-reading

through a sonata recital for him. He encouraged the pianist to come to

London, which by coincidence he was doing the very next day. Most close

friends of Harty called him Hay (a play on words contraction of ‘Hale

and Hearty’) but I suspect only Squire called him ‘Laddie’. He also

encouraged him to write his memoirs but only a brief few pages were

written before Harty died in 1941 - the same year, incidentally, that

Squire retired from active performance. Harty once called Squire ‘a

splendid virtuoso and also one of the wisest and most broadminded of

men’.

Beatrice Harrison had already made two recordings with Elgar for HMV of

the concerto, the first being abridged. Its dedicatee, Felix Salmond,

had recorded for Vocalion in the early 1920s but in any case he had left

for a career in America. The obvious person for Columbia was Squire in

his second and last concerto recording. As Obert-Thorn notes this was -

in contradistinction to the Saint-Saëns - a remarkable piece of

recording for its time. And he has had access to test pressings which

sound even better than commercial copies. A quick listen to the original

78s of both this and the Saint-Saëns indicates how well the recordings

have been served. The Elgar Pearl CD transfer [GEM0050] is easily

surpassed - notice how the wind choir sound is clarified via the test

pressings and how the cello doesn’t boom, as it’s prone to do in Pearl’s

transfer. A higher ratio of surface noise is all to the good in

Pristine’s work as it ensures an incredible amount of detailing for the

time can be heard.

Portamenti here are used as a more natural-sounding device than in the

companion work where they can sound, from time to time, gestural. The

performance is deeply felt but expressively noble; never aloof, but not

heart-on-sleeve either. From time to time one feels Harty wanting to

speed things up and when the Hallé seizes on its opportunities it does

so with vivid control. Squire gives the scherzo its metrical due, but he

is not gossamer and this is no etude-like opportunity to show off one’s

bowing. He takes his time and vests it with its own particular sense of

character. Squire takes more time in the slow movement and finale than

Harrison in her electric recording, made just the previous year, though

nowhere near the drama that du Pré and Barenboim evoke in the Adagio - a

massive six minutes to Harrison’s four and Squire’s four-and-a-half. In

the finale there’s a mix of strict rhythm and accelerandi from the

conductor, whilst the phrasal elasticity that Squire draws, supported by

rich finger position changes, is a vivid index of his art. Yes, the

next generation of cellists such as Pini, Fournier and Navarra took

things very differently - but then they weren’t born in 1871.

There are eight encores here as well, the usual sweetmeats that Squire

recorded throughout his performing life. His relaxed sense of time in The Swan

is a feature of his musicianship - he tended to have to be more

metrically strict when recording the trio repertoire - and there’s an

avuncular performance, replete with pizzicato bending, of Dunkler’s once

popular Humoresque. There’s dignity to his Handel and Bach. For

the Wagner and Mozart sides he’s joined by the organist often described

on labels as ‘Pattman at the organ’. This was George Thomas Pattman,

famed in his day, largely forgotten now. I have a Columbia white label

test pressing of this coupling and though it’s in rough-ish sound it has

rather more openness than this transfer. In fact if I’m being

ultra-critical, for my tastes more surface noise could profitably have

been left in the encore section; these sides sound just a little bit too

hemmed-in.

The most important things here are the concertos, revealing documents

both of Squire’s art and ones preserving a little slice of gramophonic

history. The transfers are mono, and there’s a brief introduction in the

inlay. I want to commend Pristine Audio’s new artwork. Previously it

was a bit haphazard, but now it looks distinguished. More than ever now,

especially since Naxos has given up on historical re-releases, we need

companies like Pristine Audio to keep producing discs like this.

Jonathan Woolf