This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Reviews

Ground-breaking early genuine stereo Beethoven recording remastered!

"Gieseking, at the height of his powers in 1944, is deft, delicate, infinitely resourceful" - Gramophone

The 1944 recording of Walter Gieseking playing brilliantly Beethoven's Emperor Concerto sits among a select few stereo recordings made experimentally prior to the 1950s, the earliest dating back to the early 1930s. It's one of the only complete works recorded in stereo prior to the general adoption of stereo recording in the 1950s - only one other stereo recording (of a single movement) is known to survive from 1944, also recorded in Germany. It was the development of tape recording which made stereo technically feasible - not until 1958 would disc replay catch up - and the Germans were a considerable way ahead on tape technology by 1944. Even so, the high levels of hiss on this recording - unsurprising given that each channel has half the tape width and thus double the noise levels - shows much was left to be done.

As well as improvements to the sometimes wayward and ill-defined stereo imagery, I've sought to reduce tape hiss, enhance the overall tonal balance, flatten out wow and flutter, and give this historic recording as good an outing as it's ever had. The 1951 EMI studio recording of the Fourth Concerto was of course made in easier conditions (no anti-aircraft fire in the background either!) but was far from perfect. I've been able to fill out the orchestral tone considerably, whilst cutting tape hiss back. The piano tone remains mellow and warm, but occasionally less than brilliant during louder passages, where I've had to fight against some peak distortion, though this is happily insufficient to distract from what is a truly superb account of the concerto.

Andrew Rose

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Op. 73, "Emperor"

Recorded Autumn 1944, Berlin

Producer/engineer: Dr. Hans Joachim von Braunmühle

Transfer from Varèse Sarabande VC 81080

A stereo recording

Berlin Reichsender Orchestra

Artur Rother conductor

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 4 in G, Op. 58

Recorded 9-11 July 1951, Kingsway Hall, London

Producer: Walter Legge

Engineer: Douglas Larter

First issued as Columbia 78s LX 1443-46

First LP issue Columbia 33C.1007

Presented in Ambient Stereo

Philharmonia Orchestra

Herbert von Karajan conductor

Walter Gieseking piano

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, June 2013

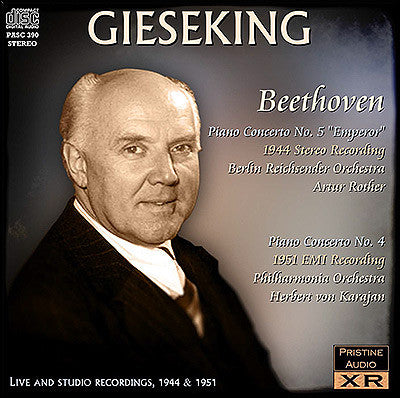

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Walter Gieseking

Total duration: 68:20

REVIEW Piano Concerto No. 5, "Emperor"

Gieseking, at the height of his powers in 1944, is deft, delicate, infinitely resourceful. From the moment of the piano’s re-entry, Gieseking points our attention away from heroic postures (though he has strengths in reserve) towards that visionary mood which underwrites the whole of the Violin Concerto and subtly pervades the Emperor, too. The recording was made at a concert in Berlin and claims to be a genuine stereo recording, a precocious example of the highly sophisticated Berlin Radio system and its Magnetophon recorders. Clearly it is a stereo recording in the same way that an 1840s Fox Talbot is a photograph, but the stereo images are vague and the level of background hiss is almost unacceptably high. That said, the beautifully natural, slightly recessed concert hall image serves Gieseking well; and the orchestra, which is immaculately conducted by Arthur Rother, is finely focused. In the latter part of the first movement cadenza artillery can be heard dimly popping and pummelling in the background, much as it probably did at the time of the work’s première in war-torn Vienna. Gieseking, ever the poet and professional, remains perfectly poised, whilst the horns sweep calmly and steadily in.

R.O., Gramophone, January 1980

REVIEW Piano Concerto No. 4

Here, I venture to suggest, in the Gieseking-Karajan G major Concerto, we find almost the ideal recording ; sides 3 and 8 in particular seem to me as nearly perfect examples of reproduced sound as one is ever likely to meet. Gieseking’s approach to Beethoven is suitably gentle and caressing ; but he can be dramatic at will, and his good musical manners are no sign of weakness or mere amiability. Technically, he exhibits a remarkable power of light but firm emphasis. His touch is even sure when he wishes to vary it, which is the equivalent of saying that he has perfect control ; that would be wasted had the pianist not also the musical mind to inform his fingers. He seems to play the G major with the utmost naturalness, as though he were a learned and fluent and friendly improviser in a tautly listening party. The secretive opening of III on side 6, the brilliance of side 2, the flourish in the cadenza and the sweet-natured reentry of the first subject are tokens of his success. The balance between soloist and orchestra is right, the ensembles are warm and rich, the tuttis never alarming. I particularly like the weight of the strings and the even distribution of tone across the orchestral gamut.

H.F., The Gramophone, November 1951

Fanfare Review

A wonderful disc all round

Pristine Classical has given the avid collector a wealth of material, and this issue is no exception. The performance of the “Emperor” was taped in “experimental stereo,” an indication, perhaps, of the innovations of the Nazi era, and so it is that the 1944 No. 5 presented here is in stereo, but the later 1951 No. 4 is in mono.

This is in fact Gieseking’s second “Emperor” and was recorded in the autumn of 1944, a decade after the first (Bruno Walter/VPO). To follow were the famous traversals with Karajan (1951, Kingsway Hall, Philharmonia) and the 1955 Philharmonia (again, but with Alceo Galliera at the helm).

Pristine certainly seems to have been successful with hiss. The recorded sound in Berlin is remarkable, excellent pretty much throughout, especially where the piano is concerned. Performance-wise, the first thing one notices about the orchestra is the sense of discipline. Accents are visceral; complementing this, there are moments of great beauty from Gieseking. Rother always keeps the momentum going, refusing to relax as some do. Perhaps one should really point to some lost detail around the 10-minute mark; that the recording does shrink a little around Gieseking’s climactic chords thereafter; and that there is a very careful piano/orchestra arrival at one notoriously tricky spot (12:26 here), where Gieseking actually stops the upward scale to co-ordinate with the orchestra’s re-entry. As if finally entering into Rother’s approach, the piano’s riposte to the return of the grand opening orchestral chords is very rapid-fire, almost dismissive. The luster on the strings of the slow movement is marvelously preserved, and the magic of Gieseking’s rapt playing is magnificent. The Finale brings plenty of fire from both pianist and orchestra. Gieseking’s fingerwork is terrific and there is plenty of energy all round. Again, there is little space for relaxation, but the effect is not of breathlessness.

The Columbia Beethoven Fourth with the Philharmonia and Karajan is centrally placed in Gieseking’s discography of this work (Böhm/Dresden Staatskapelle and a Berlin RIAS under Doráti on one side; Keilberth with WDR Cologne and Philharmonia/Galliera on the other). Just for the meeting of minds of Gieseking and Karajan, it has huge value. Gieseking’s simply gorgeous tone for the opening, coupled with his not too languorous approach, sets the parameters for a very special reading. Karajan shapes the orchestral exposition impeccably, and it is clear that the Philharmonia responds to his every whim. Gieseking plays with the utmost sensitivity, and this “notiest” of Beethoven’s concertos is perfect for him with his mastery of filigree. The strings in the famous slow movement come across with real presence. Perhaps it is in the Finale that the differences between pianist and conductor come to the fore. Basically, Karajan ensures the Germanic side of things is looked after, while Gieseking finds a more delicate space. The very close of the work is not intended to be a sudden surge of adrenalin here, and as such it fits in beautifully within the overall conception as it leads to Gieseking’s bejeweled final measures. A wonderful disc all round.

Colin Clarke

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:3 (Jan/Feb 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.