This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

Bruno Walter, "whose reading may be accepted as authentic", conducts Mahler's 2nd

Fabulously improved sound quality for "this admirable issue" in this 32-bit XR remastering

As with other issues in this series of Bruno Walter's Mahler recordings, Pristine's 32-bit XR remastering system has succeeded in delving deep into the original recording to reveal new depths and new heights. Where previously the brass sounded perhaps a little veiled, now they can be heard in all their blazing glory. Meanwhile the choir opens out wonderfully, making previous issues sound perhaps a little strangled by comparison. Finally the full rumbling majesty of the lowest organ stops can be felt as well as heard to marvellous effect. The Gramophone's reviewer talks about an "apocalyptic" performance - now we can hear it in sound to match that artistic vision.Andrew Rose

MAHLER Symphony No. 2, Op. 47 "Resurrection"

Emilia Cundari soprano

Maureen Forrester contralto

Westminster Choir

John Finlay Williamson chorus master

New York Philharmonic Orchestra

Bruno Walter conductor

1st mvt. recorded 17 February 1958

2nd & 3rd mvts. recorded 21 February 1958

4th & 5th mvts. recorded 18 February 1957

Carnegie Hall, New York

First issued as Columbia M2L 256

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, April 2013

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Bruno Walter

Total duration: 79:40

REVIEW 1959 UK LP issue

In good time for next year’s Mahler centenary comes a recording which is certain to make a strong appeal to all real Mahler enthusiasts, all the more since it is conducted by the composer’s distinguished disciple, Bruno Walter, whose reading may be accepted as authentic and who clearly loves this music. The Second Symphony, provided by Mahler with a weighty “programme” about life and death, the Last Trump and the resurrection of the dead, and the assurance of a life hereafter (“Sterben werd* ich, um zu leben”), is nevertheless a work which takes a good deal of stomaching. Faced with concepts of such magnitude, Mahler becomes merely grandiloquent: the enormous apparatus he demands—a huge orchestra, with large reserves of extra brass and percussion, organ, chorus and soloists—ends jby becoming unwieldy; the suspicion increases, as the symphony’s vast length unfolds, that it would have been the better for more matter and less art; and it cannot be denied that at the very point where nobility of thought is needed, Mahler (like Strauss in a similar context) falls dangerously near bathos. For all that, beneath all the pomp there lie some characteristically striking and beautiful ideas, and when Mahler, for contrast, reverts to the vein of childhood innocence and naivete—as in the Landler movement - (based on one of the Knaben Wunder horn songs)—he is at his most charming. Indeed, there may be more of heaven here, as seen through the eyes of a child, than in all the alarums and excursions later.

The Klemperer recording which has been the only one available until now was not particularly satisfactory, owing to the general sense of constriction, the restricted dynamic range and the string quality, which tended to sound starved just when it should have been most opulent. The present issue, except for a short patch in the finale where the engineers, not altogether surprisingly, seem to have feared for the safety of their equipment and have brought their fader down a notch or so, is remarkably well recorded, with particularly good balance and excellent quality. Adequately to contain Mahler’s vision of the heavens opening, with trumpets disposed to right and left, near and far, stereo at least is called for (and, in fact, the stereo version exists in America); but even in mono this does not overload. It is Walter’s interpretation, however, which is the real joy of this issue: not only is he more apocalyptic than Klemperer, but in the lyrical passages he brings far more grace to the music. The second subject of the opening movement, for example, has more Viennese charro, without, as in the previous recording, turning into mere goo at the recapitulation; the Landler flows more easily (what lovely singing tone from the ’cellos, incidentally!); and the Scherzo, which before seemed unduly protracted, is taken at a better speed and is more pointed rhythmically. Though one should not forget the wonderfully steady singing of Hilde Rössl-Majdan in the earlier set, the soloists and chorus here are very good, and complete the attraction of this admirable issue.

L.S., The Gramophone, June 1959

MusicWeb International Review

This is an essential interpretation

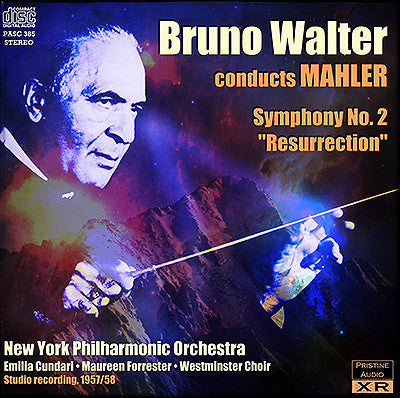

Pristine has chosen a striking cover design for

this issue to reflect the cosmic nature of the Resurrection Symphony:

artwork based on photos from the Hubble Space Telescope is used as the

backdrop to the image of Bruno Walter, baton poised. This is a recording

that was almost never completed: the sessions were delayed by a year

following Walter’s heart attack in March 1957, just after he had

recorded the fourth and fifth movements.

Walter’s way with this mighty work has been revered since it first

appeared; regarding its musical content, I have nothing much to contribute

beyond reiterating the many virtues already commented upon by previous

reviewers. This is a recording which belongs in every serious Mahlerian’s

collection; the question is whether a newcomer or an established collector

should contemplate forking out for this XR re-mastering by Andrew Rose.

I have long been a fan of Pristine’s engineering and just recently

extolled the extraordinary clarity and depth which Mr Rose has breathed

into the Furtwängler La Scala Ring. I am invariably impressed

by what he can do for venerable recordings and I can certainly hear

how he has reduced hiss, enhanced lower frequencies and revealed the

brass and chorus in greater glory. However, after repeated close comparison

with the CBS issue - originally very well recorded by Philips - I cannot

in all conscience claim that anyone who already owns it need rush to

replace it with this Pristine single disc, especially as the CBS double

CD set, offering the First Symphony too, is available at bargain prices.

Indeed, occasionally I even felt that that the CBS engineering retained

more bite and body than the Pristine version.

Walter’s vision for this work is one of quiet mastery and concentration;

there is nothing showy or interventionist about his conducting but under

his direction the music seems always to be doing just what it should.

He never lingers or indulges and those looking for the equally masterly

but very different, slower approaches of Tennstedt or Levine or Klemperer’s

more granitic assault, will be surprised. Walter’s version fits

neatly onto one disc but he never seems to be rushing. He storms heaven

with an orchestra - here correctly credited as the New York Philharmonic,

which was originally billed as the “Columbia Symphony Orchestra”

for the usual contractual reasons - which plays out of its skin.

The key to the first movement lies in the instruction “maestoso”;

Walter maintains a steady, majestic and inexorable stride in this funeral

march, but also permits the pastoral interludes to unfold gently, uniting

the two moods with a firm sense of purpose. His control is absolute;

he knows how to meld the contrasting and conflicting moods into a coherent

narrative. When the menacing opening theme returns on the insistent

brass, the discords build and build to a thrilling climax at 14:54 before

the tantalising offer of consolation subsides into a wholly ambiguous

conclusion, reflecting Mahler’s ambivalence about his search for

God; Walter displays a wholly convincing understanding of the spiritual

dimension of this symphony.

The Andante unfolds with lilt and charm; Walter’s subtle rubato

and the singing cello tone effortlessly convey the recollection of happy

memories in a past life. This restrained style perhaps carries over

too much into the “St Anthony preaching to the fishes” movement,

eliciting a criticism from some quarters which has some validity, that

he is a tad too blithe and relaxed to capture fully the grim and bitter

irony of the saint’s efforts; the music here should sound like

a metaphor for the circularity and pointlessness of life’s frustrations,

but yet again Walter secures a powerful close to the movement.

“Urlicht” is tender and prayerful, as it should be. Maureen

Forrester’s smoky, rich-toned contralto, with its appealing, flickering

vibrato, is amongst the very best in this music; only Janet Baker in

her many versions and perhaps Jessye Norman for Maazel surpass her.

The monstrous finale is simply glorious: Emilia Cundari - a singer with

whom, I confess, I am entirely unfamiliar - is silvery and soaring,

while Forrester intones her text like the Cumaean Sibyl. The Westminster

College Choir is wonderfully expressive, first mysterious, then impassioned

and ecstatic. The otherworldly off-stage effects in the “Grosse

Appel” are highly effective and in the last ten minutes are amongst

the most serene and ethereal of any recording. Consistent with his strategy

in directing the whole symphony, Walter makes a slow-burn progress towards

an overwhelmingly powerful climax.

Whether you buy it on Pristine or CBS, this is an essential interpretation.

Ralph Moore