This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

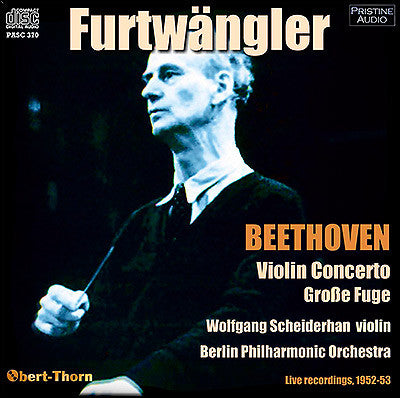

Elusive live Furtwängler recordings of Beethoven's Violin Concerto & Große Fuge

Superb new transfers by Mark Obert-Thorn for Pristine

The present recording of the Beethoven Violin Concerto with Schneiderhan and Furtwängler is among the most elusive of the conductor’s performances on CD. First released in 1964 as part of a series of Deutsche Grammophon LPs marking the tenth anniversary of the conductor’s death, this broadcast has received less attention over the years than his three recordings with Menuhin (two studio, one live) and the wartime version with Erich Röhn taped at the last BPO concert in the old Philharmonie before it was destroyed. It has been transferred here from a 1970s monaural Heliodor LP pressing, as has the Grosse Fuge, which has a similar release history.

The pitches have been left as they appear on the LPs at around A4=445Hz when played at 33.3 rpm, which is in line with what is known about the BPO’s higher tuning during this period and the evidence of their other contemporaneous recordings.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

BEETHOVEN Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61

Wolfgang Schneiderhan violin

Recorded during the performance of 18 May 1953 in the Titania-Palast, Berlin

First issued on Deutsche Grammophon LPM 18855 -

BEETHOVEN Große Fuge, Op. 133

Recorded during the performance of 10 February 1952 in the Titania-Palast, Berlin

First issued on Deutsche Grammophon LPM 18859

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Wilhelm Furtwängler conductor

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Furtwängler

Total duration: 63:09

Fanfare Review

Those with a serious interest in Furtwängler should find this of real value.

Wilhelm Furtwängler left five recordings of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, with three different soloists. There are two commercial studio recordings, both with Yehudi Menuhin, and three live performances, one each with Menuhin, Erich Rohn, and Wolfgang Schneiderhan. This Schneiderhan performance (May 18, 1953) has long been the neglected stepchild of the five, and now it receives what is by far its finest transfer, overseen by Mark Obert-Thorn. The result may lead to a reassessment of its merits.

In his invaluable book The Furtwängler Record, John Ardoin dismisses Schneiderhan’s performance as “technically efficient but poetically deficient,” and calls the entire performance “aloof, often brusque and monochromatic.” That doesn’t match what one hears on this Pristine Audio reissue. Going back and listening to my Japanese DG version, I can see what led to that conclusion. The more constricted sound of that edition (the only prior one with which I am familiar) takes away from the color of the performance.

To be sure, this may still be the least desirable of the Furtwängler performances of this concerto, and only serious Furtwängler collectors are likely to be interested in it. The wartime performance by Rohn, part of the final concert at the old Philharmonie prior to its being bombed by the Allies, has about it the white heat we have come to expect from Furtwängler performances of that period, and Rohn is on fire throughout. The Menuhin performances are masterful; two supreme musicians meeting on common ground. The 1947 Lucerne Festival performance is perhaps the finest—in part fueled by the special significance of Menuhin’s decision to be, quite consciously, the first Jewish soloist to appear with Furtwängler after the war. Menuhin vigorously defended the conductor against those who pilloried him for remaining in Germany during the war years, and offered to perform with him just months after the conductor had been officially de-Nazified.

Getting back to this particular performance, one of its singular features is Schneiderhan’s use of the Joachim cadenzas instead of the more commonly heard Kreisler ones. The overall performance is more middle-of-the-road than the others. Schneiderhan does not provide the incendiary passion found in the Rohn performance nor the majesty and extraordinarily expressive emotion in the Menuhin performances. The slow movement in the Menuhin versions displays a freedom that virtually renders bar lines invisible. In comparison with that, Schneiderhan can seem a bit pedestrian. But when heard without adding the context of other performances, there is in fact real poetry in the Larghetto here, and genuine thrust and dramatic weight in the outer movements.

As filler, Pristine has chosen the February 10, 1952, performance of the Grosse Fuge for string quartet, arranged here for full string orchestra. Furtwängler wrote that “Experience has shown that the monumental character of the Grosse Fuge is brought out more effectively than by a string quartet.” I might not agree with him that the orchestral version is preferable, but neither do I feel it should be sneered at by purists. This music does appear to be straining at its boundaries in the quartet version, though that is probably a good part of its appeal. The sheer force and cumulative power of the music in this string orchestra version, especially under Furtwängler’s leadership, is a unique and valuable experience on its own terms. Ardoin has a strong preference for the Vienna Philharmonic performance under Furtwängler, from the 1954 Salzburg Festival. While I agree that it is the more elegant and chamber-like of the two, there is something to be said for the gruff force and tensile strength of this Berlin reading. As with the concerto, the sonic restoration is excellent, although Obert-Thorn was working from more limited original source material. The sound quality lacks the impact heard in the concerto.

Overall this constitutes an important release on the Pristine Audio label, because it makes available for wider circulation two Furtwängler performances that have been under the radar for a long time. While general collectors will probably look elsewhere, those with a serious interest in Furtwängler should find this of real value.

Henry Fogel

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:6 (July/Aug 2013) of Fanfare Magazine.