This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

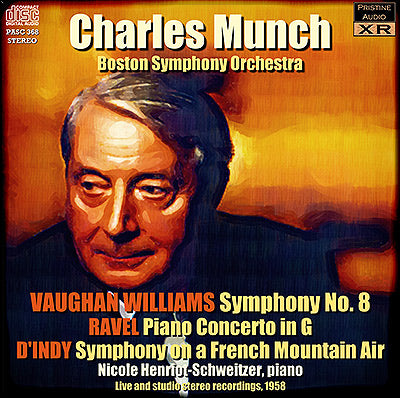

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

Fabulous and unique recording of Vaughan Williams' 8th Symphony by Munch

Plus superb stereo recordings of Ravel and d'Indy, all in new 32-bit Pristine XR remasters

The restoration and remastering of this release has been particularly fascinating for me. First of all we have what would appear to be the only extant recording of Vaughan Williams' Symphony No. 8 in D minor which features neither a British orchestra nor a British conductor. Indeed we can only trace one other recording of the work, made in the late 1950s with Barbirolli conducting the New York Philharmonic, which was not made with a British orchestra. Previously unreleased, Munch and the Boston Symphony make a superb job in this broadcast recording from the Berkshire Festival at Tanglewood - some may even find this the finest recording this symphony has ever had; it's certainly how it was introduced to me.

We opted to couple the Vaughan Williams with the commercial Ravel and d'Indy recording partly because of the links between the two French composers and Vaughan Williams. Seeking advice over orchestration, he was advised early in his career to study with both Frenchmen, and indeed did spend time working under Ravel in 1908, who described Vaughan Williams as the only one of his pupils who didn't write music like his own.

The discs used for these transfers are contemporary audiophile pressings on the Classic Records label, remastered from the original RCA Victor master tapes and pressed onto 200g single-sided vinyl at 45rpm for maximum fidelity. Despite some unexpected technical difficulties experienced with the discs themselves (all easily resolved in the restoration process), the sound quality is indeed superb here. Further impressions of these discs can be found in our newsletters of 16 and 23 November 2012, archivedhere at the Pristine Classical website.

Andrew Rose

-

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No. 8 in D minor

Recorded 2 August 1958, live at the Music Shed, Tanglewood, a Berkshire Festival Concert

- RAVEL Piano Concerto in G minor

-

D'INDY Symphony on a French Mountain Air (Symphonie sur un Chant Montagnard Français), Op.25

Nicole Henriot-Schweitzer piano

Recorded 28 March 1958

Issued as RCA LSC-2271

Transfers from Classic Records LSC-2271-45

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Charles Munch conductor

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, November 2012

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Charles Munch

Total duration: 76:25

REVIEW d'Indy Symphony (1995 reissue)

Nicole

Henriot-Schweitzer in the d'Indy has the handicap of a tap-room piano,

but the poise, delicacy and spirit of her playing shine through (her subito and sustained pp from

4'36" in the first movement, is, like much else here, utterly

enchanting). Munch takes a fresher view of the score than many

latter-day interpreters, and judges to perfection the difficult tempo

relationships in the central Assez modéré. Had not Dutoit (with

Jean-Yves Thibaudet) come up trumps with a recent account of the d'indy

that must be one of the finest things he has done in Montreal

(full-price coupled with the Franck Symphony), this Boston account would

be a clear first choice.

J.S., Gramophone, May 1995

Fanfare Review

I consider this to be a Vaughan Williams Eighth that is the equal of any

Ralph Vaughan Williams was 83 years old when he completed his Eighth Symphony. It seems like an experiment in sonorities, featuring the woodwinds and brass in the second movement, the strings in the third, and a full battery of percussion instruments supporting the orchestra in the finale, which calls for five percussion players. The score lists parts for side drum, triangle, cymbals, bass drum, vibraphone, xylophone, glockenspiel, tubular bells, and three tuned gongs “as used in Puccini’s Turandot.” I’d love to be present at a performance so I could revel in the din of the percussion in the finale. If I have any disappointment with the subsequent recordings (all of which I have owned at one time or other), it’s that the percussion section doesn’t make enough of a racket. The percussionists in this August 1958 performance from Tanglewood, the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s summer home, I am happy to say, are among the louder ones. The score also gives a suggested timing of 26:30. On recordings, one conductor, Leonard Slatkin, brings the piece in close to that, at 26:27. John Barbirolli, to whom the symphony is dedicated, managed a 26:43 timing shortly after the 1956 premiere but several years later, had slowed down to 28:57 for a BBC broadcast. Haitink, Stokowski, and Thomson manage to stretch it out to more than a half-hour. I am not, however, judging by stopwatch—all of the recordings I’ve heard (16, including another Munch performance that is faster than this one) are certainly “good” ones and among my particular favorites are some of the slower ones, including this charged-up Munch performance. Timing wise, it’s in the middle of the pack, at 28: 19. Pristine’s notes claim it to be stereophonic but when I listened to it, it just sounded like enhanced mono. So I took out my headset and discovered that Pristine’s stereo claim is accurate…but the channels are reversed. I saw many Munch concerts and his preferred seating was violins on his left, cellos and violas on the right, the latter on the outside. No wonder I couldn’t get those violins into the left channel! Since I can live with the reversed channels, I consider this to be a Vaughan Williams Eighth that is the equal of any. Two oddities: This is the first symphony to which Vaughan Williams actually assigned a number; it is also only one of two RVW symphonies that have a loud ending.

Since Pristine must have wanted something else by Munch to fill out the CD, the producer came up with two French works for piano and orchestra that were recorded by RCA Victor a few months before the Vaughan Williams performance. The pianist, Nicole Henriot-Schweitzer was, I believe, Munch’s niece. She had previously recorded the Ravel Concerto with him leading the Paris Conservatory Orchestra for Decca London about a decade earlier and proceeded to record it with him again with the Orchestra of Paris for EMI. Munch had recorded the d’Indy with Robert Casadesus and the New York Philharmonic about a decade earlier as well. In his annotations, the producer gripes about the sound of the piano but I had no problem with it and the balance between soloist and orchestra is just fine. If these are not necessarily my favorite recordings of the pieces in question (Zimerman/Boulez and Larrocha/Slatkin in the Ravel—Casadesus/Ormandy, which is faster, Johannesen/Goosens, which is slower, and Thibaudet/Dutoit, which is similar, in the d’Indy), they are nothing less than first-class renderings of the music and sound marginally superior to my original RCA Victors. No one would go wrong with them. For what it’s worth, with three recordings of the G Major and three of the Concerto for the Left Hand (with Jacqueline Blancard, Alfred Cortot, and Jacques Février), Munch is the all-time leader in recordings of the Ravel concertos.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:5 (May/June 2013) of Fanfare Magazine.