This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Reviews

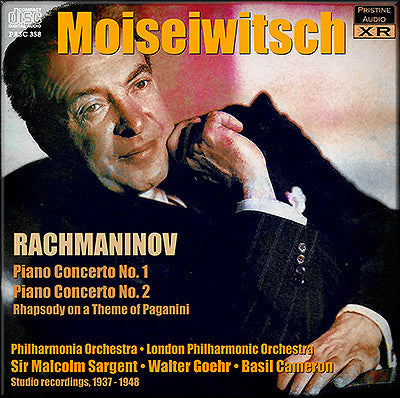

Moiseiwitsch, Rachmaninov's "spiritual heir" - the orchestral recordings

Dramatic improvements in sound quality from these new 32-bit XR remasters of classic interpretations

These new transfers bring demonstrate brilliantly the way that the latest technologies can really bring recordings like these back to life. Pitch stabilisation software, available now for a little over a year, is key to firming up the sound of older piano recordings, reducing or eliminating the wow and flutter that characterises just about all of them.

XR remastering, with its carefully tailored re-equalisation, noise reduction and click and crackle elimination sheds years from the sound of both soloist and orchestra as the inadequacies of early recording equipment are ameliorated. Finally, the subtle use of convolution reverberation replaces the typically dead studio acoustics of the era - all of these recordings were made in Abbey Road's Studio 1 - with the genuine and musically-sympathetic acoustic of one of the world's finest concert halls, greatly enhancing the sound both of the piano and the orchestra. In each case accurate measurements of residual electrical signals present in the recordings have allowed precise pitching to match that of the original performances.

The results, I trust, speak elequently for themselves.

Andrew Rose

-

RACHMANINOV Piano Concerto No. 1 in F sharp minor, Op. 1

Recorded 23 December 1948

Issued as HMV C.3932-34

Matrix Nos. 2EA.13511-16

The Philharmonia Orchestra

Sir Malcolm Sargent conductor

-

RACHMANINOV Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18

Recorded 24 November

& 13 December 1937

Issued as HMV C.2973-76

Matrix Nos. 2EA.5903-5910

London Philharmonic Orchestra

Walter Goehr conductor

-

RACHMANINOV Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43

Recorded 5 December 1938

Issued as HMV C.3062-64

Matrix Nos. 2EA.7178-83

London Philharmonic Orchestra

Basil Cameron conductor

Recorded at Abbey Road Studio 1, London

Benno Moiseiwitsch piano

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, September 2012

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Benno Moiseiwitsch

Total duration: 78:19

REVIEW Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No. 1, 1949

Do not let that awe-inspiring label "Op. 1" mislead you into any false ideas: for though this concerto was written in 1892, just before the student Rachmaninov left Moscow Conservatoire, he later considered it too jejune for performance, and in 1917 completely revised it —so that in its present form it dates from after the Third Concerto! It is dedicated to his cousin Siloti, as a result of whose efforts it was that he was cured of a dangerous fever which he had contracted. This First Concerto has never reached, and probably never will reach, the popularity of its successors—even in its revised form it retains its air of immaturity—but it nevertheless contains many characteristic passages which are of great interest to the student of Rachnaaninov's style.

The first movement is rhapsodic in character. After a challenging fanfare and an impetuous cadenza from the piano, it opens with a broad and elegiac string melody which, however, very shortly gives way to a scherzando section, which itself lasts next to no time before changing mood again. There is a youthful prodigality of melodic invention throughout the movement, but the general effect is of a series of loosely constructed ideas, constantly stopping and restarting. It is much to the credit of this present performance that this episodic character is, so far as possible, skilfully avoided.

The Andante, a romantic movement of "nocturne" type, is by far the most successful of the three. It opens with a modulatory sequential passage (of which throughout the concerto Rachmaninov shows himself overfond), slowly veering round to the key of D major, in which the main subject appears— the true ancestor in style of all the film rhapsodies of to-day. It is completely characteristic of the composer, and I should like to draw attention to an enchanting passage in which the piano weaves colourful chromatic decorations round the theme on the strings (the last third of side 4).

The Finale is less satisfactory: it is a:trilliant, capricious movement, based on rather thin material, into which is pitchforked, without much connection, a rather sickly sentimental middle section. However, the piano writing throughout, as might be expected, is vigorous and ingenious.

No more sympathetic interpreters could have been found than Moiseiwitsch and Sargent, who give a most fluent reading of the work-actually preferable in interpretation, to my mind, to the Rachmaninov-Ormandy version of 1940, which seemed altogether too "bitty" for comfort; and this is no whit less efficient. Sargent's accompaniment in the finale is a model of its kind while an occasional faint sprinkling of wrong notes in the solo part serves as a reminder that even the best pianists are human. The piano is perhaps a shade distant—in the last movement I would have welcomed a more forward, glittering tone—but in general the recording is good, and unlike the earlier version mentioned, the fortissimos do not feel as if someone had hit one round the face with a wet sock.

L.S., The Gramophone, December 1949

REVIEW Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No. 2, 1938

Christmas pressure has resulted in this set's arriving minus the start, and a chunk out of the second movement; however, I have three-quarters of it, and that seems sufficient to operate on. I would not use the term in any hard, dissectional sense, of such an old friend as this. Next to Rachmaninov himself, I suppose few soloists would come before Moiseiwitsch, in the choice of most lovers of the work. He has been playing it to me since 1917— perhaps he began when it came out, in the early years of the century. Here it is in the C series, in which I meant, last month, to emphasize the quality (when we got Hess in the Schumann at 4s. a time). This is a movement much to be welcomed.

I start with the development on side 2, where both subjects are treated, in part. The performers back up the composer splendidly in keeping the ball in the air. How swimmingly it all goes, with those sequences that make us feel that we are travelling in the luxury of the Blue Train: everything provided for, nothing to worry about, and scenery just new enough to engage the eye above all, no foreign language to think of, for all around us speak that which we know. The interlude before the end is a charming idea; then how swiftly the composer whisks us to the finish: an entirely delightful piece of constructive art.

The slow movement is equally strongly upborne, the pianist attractively making sure that there is no sagging. After hearing the opening tune, one of my white-label sides is missing, so I resume in the middle section, and hear the last presentation of the friendly tune. In the liveliness the player gets rather hard, and he is not quite the finest singer upon the piano, is he? Yet he spreads a broad canvas that suits the music.

The finale opens in the most engaging way with those mildly tantalizing gambits. There is a touch of the work's first theme in the three-time portion which follows the piano's first turn. The full-flowing energy of the soloist is best to be appreciated in such clear-driving sections as this finale abounds in. In the last side but one, the band is not too well unified in time with the pianist: that lack of recording rehearsal for the finest finish, which I have often noted, is here again. Otherwise, I like the plain, sturdy handling of the material by the conductor; and nobody can be ignorant of Moiseiwitsch's particular style and qualities. The music bears its heart on its sleeve, and so does the pianist. There is no attempt to manufacture subtleties which the music does not seek. It is all plain, simple, and cordial. I have heard finer tone from recorded orchestras, but the discs are, in my estimation of the work and its requirements, quite adequate.

W.R.A., The Gramophone, January 1938

Fanfare Review

Superb performances, lovingly delivered by Pristine.

All three of these items hail from the HMV Plum label “C” series; recording dates are 1937, 1938, and 1949, respectively. Moiseiwitsch was to go on to rerecord the Second Concerto and the Rhapsody with the Philharmonia under Rignold in 1955 (Michael Fine reviewed the concerto in its Basics Classics incarnation in Fanfare 24:3); the recording of the First Concerto here remains his only one. But who needs another one of the First? This is one of the finest accounts I have heard. Moiseiwitsch plays with tremendous sweep and dexterity, and the whole is imbued with just the right sense of flow. Of all these attributes, the overriding one is dexterity (although there is no shortage of excitement in the finale). It is a tribute to Pristine’s engineers that so much detail is audible.

For the Second Concerto, there is a touch of blurring of mid to lower range detail (actually, just what one doesn’t want in Rachmaninoff), but not enough to detract from Moiseiwitsch and Goehr’s powerful conception. The music ebbs and flows naturally, and Moiseiwitsch’s trademark cantabile is in evidence for the long melodies. The brass appear a little muffled on occasion, but elsewhere there is plenty of detail. This may not be the most exciting of Rach Seconds, but it is one of the most considered and beautiful (the first movement horn solo is gorgeous; if anything, it is slightly understated towards the end). Pristine’s superlative transfer gives a good idea of the pianist’s golden tone in the slow movement, while Moiseiwitsch himself leaves us in no doubt of his legerdemain. There is a hint of strain in the upper frequencies in the second movement cadenza (no sense of strain from the pianist, I hasten to add); the finale sparkles, with Moiseiwitsch making light work of any passages traditionally thought of as potentially awkward. Overall, there are higher octane readings. It is worthy of note that the live performance from the Proms on BBC Legends (4074, coupled with a 1963 Festival Hall “Emperor” that is full of risk-taking) acts as a worthy supplement to this one.

The Paganini Rhapsody is simply magnificent. The Pristine transfer enables a huge amount of detail to come through. While the famous 18th variation is lovely, it is the gossamer lighter-fingered passages that are most memorable. If there are readings that imbue the work’s final gestures with more humor (I think of the Ashkenazy/Previn Decca performance), Moiseiwitsch’s deft end comes after superb, and highly exciting, preparation. Importantly, in this piece, there is a palpable connection between soloist and his conductor, Basil Cameron, throughout. It is testament to the quality of the transfer that I essentially forgot any sonic limitations and concentrated purely on the music. Superb performances, lovingly delivered by Pristine.

Colin Clarke

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:4 (Mar/Apr 2013) of Fanfare Magazine.