This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

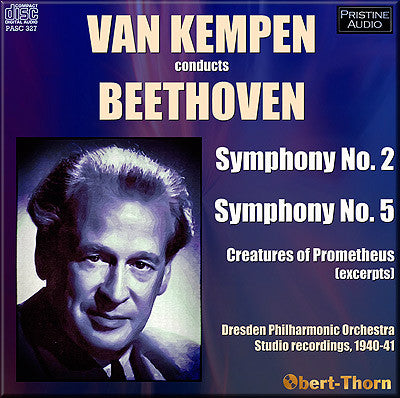

Paul van Kempen's Dresden Philharmonic tackles major works by Beethoven

Excellent wartime recordings in fabulous new Obert-Thorn transfers

The sources for the transfers were postwar yellow-label DGG shellac pressings for the Creatures of Prometheus selections and black-label wartime Polydors for the symphonies. Despite their occasional sonic imperfections, these recordings are significant in that van Kempen did not return to these scores in the studio in the LP era. As far as I am aware, the Prometheus excerpts and the Second Symphony have never appeared on CD before.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

BEETHOVEN The Creatures of Prometheus, Op. 43 - Overture, Ballet No. 8

Recorded 7 July 1941 in Dresden

Matrix nos.: 1683 ½ GS 9, 1684 ½ GS 9, 1685 ½ GS 9 and 1686 ½ GS 9

First issued on Polydor 57156 and 57157

-

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 2 in D major, Opus 36

Recorded April, 1940 in Dresden

Matrix nos.: 1308 ½ GE 9, 1311 ¾ GE 9, 1312 ½ GE 9, 1313 ½ GE 9, 1314 GE 9,

1315 ¾ GE 9, 1316 ½ GE 9, 1317 ½ GE 9 and 1318 ½ GE 9

First issued on Polydor 67608 through 67612

-

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

Recorded 7 July 1941 in Dresden

Matrix nos.: 1509 ½ GE 9, 1510 ½ GE 9, 1511 GE 9, 1512 GE 9, 1513 ⅝ GE 9,

1514 ½ GE 9, 1515 ⅝ GE 9, 1516 ⅝ GE 9 and 1517 ½ GE 9

First issued on Polydor 67635 through 67639

Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra

Paul van Kempen conductor

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Paul van Kempen

Total duration: 79:16

MusicWeb International Review

A heartfelt warmth, unhurried grandeur where required and some beautifully limpid wind playing

The Dutch conductor Paul van Kempen (1893-1955) has been a name that crops up rather than a constant presence in the world of recorded music. There are those who prefer Wilhelm Kempff’s first cycle of Beethoven concertos not least on account of Van Kempen’s conducting. His easy cohabitation with the Nazi regime did not endear him to his own countrymen or help him to rebuild his career in Holland after the war. His recordings were not numerous and he did not make later LP versions of any of the works on this issue. As transferred by Mark Obert-Thorn these discs have good presence and body and a wider dynamic range than was common at the time. This raises the question whether Van Kempen himself did not insist on a wider dynamic range than many of his contemporaries on the podium. The gentle, unforced lyrical playing of the quieter passages combined with the often forceful approach to fortes suggest this may have been the case.

Van Kempen is said to have had an eruptive musical personality, particularly suited to Tchaikovsky. This is not notably born out in the Prometheus Overture, where a nicely shaped introduction is followed by a vigorous but unexceptionable allegro, nor in the Ballet Music, where a degree of un-balletic overemphasis seems to stem from Beethoven himself. It is noticeable at a few points in the outer movements of the Second Symphony, where the music is momentarily pushed ahead of the well-chosen tempi and a touch of hysteria enters the proceedings. On the other hand, the slow movement is beautifully shaped, at a fairly slow tempo but not so slow as to lose a very natural sense of flow. This movement can overstay its length; this is, for me, a rare case among slower versions where this did not happen.

The first movement of the Fifth also has a few odd moments of incipient hysteria, though they cannot conceal the fact that most of it is very effectively hammered out while the few lyrical moments are really beautiful. Van Kempen’s shaping of the blunt chords shortly before the recapitulation points out - uniquely in my experience - which of the two chords is harmonically the more important. He is also very un-indulgent - especially by the standards of his time - over the famous four-note motive, for which he slows down hardly at all.

The scherzo is steady but well-sprung and very clear. The justification of a steady scherzo, though, is that the difficult trio doesn’t become a scramble. Unfortunately the eruptive Van Kempen intervenes and things get a bit scrappy. The finale is launched in fine style, but shortly after the beginning of the development there is a loss of tension, the tempo slightly slackens and even the recording has less presence. I don’t know where the side joins were - all power to Obert-Thorn for linking them up so seamlessly - but I’m wondering of the proceedings were interrupted at that point, maybe for some time, and did not immediately pick up with the same degree of tension.

Which leaves the slow movement. Taken on the slow side it has a heartfelt warmth, unhurried grandeur where required and some beautifully limpid wind playing. This brings back the old, never-answered question. should something recorded in wartime Nazi Germany express such timeless, benign humanity?

Readers will have decided long ere now whether this latter aspect worries them. In any case, I’d say that these are not exactly essential Beethoven performances. But those with large collections and a fascination for the interpretation of these inexhaustible works should find a place for them. They may well conclude that the slow movements are among the finest in their library.

Christopher Howell

MusicWeb International

MusicWeb International