This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

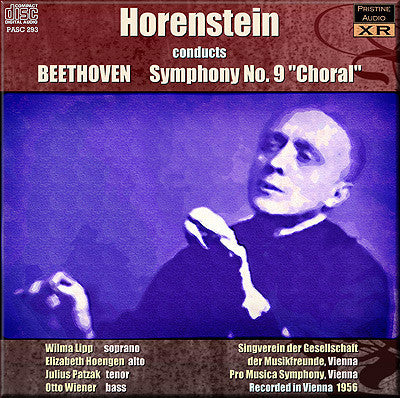

Horenstein's classic 1956 recording of the Choral Symphony

Sounding fabulous in this new 32-bit XR transfer and remastering

Horenstein's Beethoven Nine is that rarest of things - a recording of the symphony which fitted onto a single LP, rather than the more common three sides. This was achieved both by having some quite lengthy sides - the label claims 33 minutes and 32 minutes duration, with a split partway through the third movement - and by Horenstein conducting the work at a fair old lick. I compared it to a later recording by Solti, which runs to a more leisurely 76 and three-quarter minutes. Whilst their 2nd and 4th movements are relatively similar, Horenstein's first movement is nearly 3 minutes quicker than Solti's, and his third is almost 33% faster and thus five minutes shorter.

In remastering I discovered a huge amount of detail which the rather veiled 1956 production had left hidden, and the XR remastering restores a sparkling vitality to the music which matches Horestein's pace and delivery well. I noted that the original LP production faded the master tape to silence between movements, and this has been done here as well - and I was able to take the opportunity to add some vital inter-movement breathing space.

On my near-mint pressing the second side presented a greater degree of surface swish than the first, which has been treated. I also excised an insect-like lathe whistle which was audible for much of the first side, warbling around 4.5kHz.

The end result is a particularly fine-sounding production of exceptional clarity.

Andrew Rose

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 "Choral"

Recorded 6 February, 1956 Konzerthaus, Vienna

Transfers from Vox PL 10 000

Wilma Lipp soprano

Elisabeth Hoengen alto

Julius Patzak tenor

Otto Wiener bass

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Vienna

Pro Musica Symphony, Vienna

Conductor Jascha Horenstein

Total duration: 66:02

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, June 2011

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Jascha Horenstein

"This

record has already appeared in America and I hope our correspondent

there won't mind my tilting at his view that it is a "good but not

exactly memorable performance". For me, any performance that makes the

last movement a thrilling climax to the whole work is indeed memorable,

and how often does that happen, at a concert or on a record? (When it

does happen at a concert I am unable to enjoy it, for I am constantly on

tenterhooks, afraid that we shall be let down!) Here there is no doubt

about it: this is the most telling Finale you will find on any record at

present available. Toscanini's certainly wasn't a success: the singing

was harddriven and not always adequate, and the recording of the voices

was poor. The chorus in Furtwängler's deeply-felt Bayreuth performance

is ineffectively recorded. The same fault is evident in the most recent

issue, Karajan's on Columbia.

Horenstein has got his chorus to

sing with magnificent conviction and Vox have recorded them very well.

Their words are so vital and I can hear them so clearly that I want to

know why they (and the bass soloist) sing "fresch" instead of "streng"

in the sixth line of Schiller's poem. But there is no doubt about the

effect of their singing. The jubilance of the word "Freude" at the

start, the conviction of "Seid umschlungen, Millionen", making us feel

that they really mean what they are singing about—that all men

everywhere should embrace each other as brothers— the whole thing, in

fact, has come to life for once.

The solo voices are not quite

the equal of Furtwängler's quartet but they never let us down seriously

and they very often lift us up. The orchestral playing through the whole

work is in the first class.

True, the reading of the earlier

movements is not so great as Toscanini's, not so "dedicated" as

Furtwängler's, but it is not superficial. There are fine things, and one

magnificent moment—at the second outburst for trumpets and horns in the

slow movement, followed by deeply recorded basses in the quiet passage

that ensues. The timpanist is always noticeably good but he is brilliant

in the Scherzo. Horenstein's care for detail and balance is evident

everywhere but it is in the Finale that he really comes into his own.

And

all this is on one disc. In some of the heavier passages it does sound a

little as if it had been a push to get it all in but when I balanced

this with so many advantages I was not inclined to worry too much. And,

something that had not occurred to me, the tiresomeness of having the

flow of the slow movement interrupted by turning over the record in the

middle was considerably off-set by not having to turn it over before the

Finale—the great outburst almost breaks in upon the slow movement's

end, as it should.

This brings an impressive performance within

reach of a great many who might be unwilling to afford two discs and as

such alone is to be welcomed. But I would recommend it to anybody's

attention."

T.H. The Gramophone, April 1957

Fanfare Review

I’d now rate this as one of the great historic Ninths - Pristine’s superior sound will make you appreciate the performance with fresh ears

This 1956 Vox recording has previously appeared on CD in that label’s (generally high-quality) “Legends” series. The sound there, however, was rather dull and cavernous; Pristine’s (from Vox LPs) is brighter, with more top and cleaner textures. I have listed the orchestra under its correct identity rather than the pseudonymous “Pro Musica” used by Vox.

It was a pleasure re-acquainting myself with this performance, whose quality I had not sufficiently appreciated before. The Vienna Symphony Orchestra’s postwar studio recordings on Vox and other labels were made under hard-pressed conditions, usually with a bare minimum of rehearsal, but Horenstein’s alchemy transformed the experience from routine studio run-through to an inspirational occasion. The first movement has a lithe, classical feel, with long-breathed sweep and buoyant momentum. Textures are lean, punchy, and open (despite the less than ideally transparent recording). At the beginning Horenstein emphasizes precisely articulated sextuplets, which he brings out as a significant motivic element throughout the movement (Karajan was another conductor who did this). Tension is maintained at a high level, and the recapitulation’s major-mode “terrible brightness” is projected with tremendous rhythmic grip and an exciting sense of all-out involvement from the players. The Scherzo has an exhilarating Schwung and articulacy, with ear-catching attention to detail (e.g., the clarity and refinement of dynamic gradations in the metrically complex middle section). The Trio is notable for the Vienna Symphony Orchestra’s characterfully rustic-sounding woodwinds. Horenstein takes the brief introduction to the Adagio very slowly, in a floating, improvisatory way that effectively sets in relief the flowing tempo that follows. His fresh rethinking of the familiar music is everywhere in evidence—e.g., in his original take on the 12/8 variation (bars 99 ff.), emphasizing the slow-moving theme in the woodwinds, while the violins’ dancing embellishments recede into an evocatively shimmering background. He projects the forte fanfares (bars 121 ff.) with an ear-catchingly forceful éclat, and animates the subsequent plunge into flat tonal regions (bars 133 ff.) by an unaccustomed emphasis on the rhythmic figure in the second violins. In a final nice touch I’ve never heard anyone else bring out, he notices a subtle reminiscence of the main theme in the oboe’s inner-voice falling fourth D–A, three bars before the end. The finale does not disappoint, in a performance of formidable sweep, articulacy, and rhythmic focus, inspiring an incandescent response from orchestra and chorus. It is refreshing to hear the opening cello/bass recitatives played truly in tempo, as specified by Beethoven but rarely heard in recordings of this vintage. The mystical interlude at “Seid umschlungen, Millionen” also benefits greatly from Horenstein’s vibrant rhythmic tautness. The solo quartet is outstanding, both idiomatically and technically (especially Wilma Lipp and Julius Patzak).

Horenstein’s 1963 Paris performance (Music & Arts) is similar in conception, with the added intensity of the live occasion, but the French orchestra can be unpleasantly raw. As for other studio versions from the 1950s, Böhm’s 1957 recording with the same orchestra (Philips) is thicker-textured, better recorded but not better played; Karajan and the Philharmonia (EMI, 1955) have much of Horenstein’s drive and momentum, along with the younger maestro’s characteristic overlay of legato refinement; Schuricht and the Paris Conservatory Orchestra (EMI, 1958) are colorful and articulate but less subtle. For a comparable vitally original rethinking, you have to go back to the classic Kleiber/VPO in 1952 (Decca).

All in all, I’d now rate this as one of the great historic Ninths. Even if you already have the Vox Legends release, Pristine’s superior sound will make you appreciate the performance with fresh ears.

Boyd Pomeroy

This article originally appeared in Issue 35:2 (Nov/Dec 2011) of Fanfare Magazine.