This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

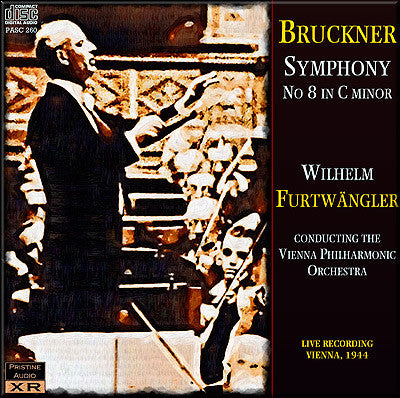

Another Bruckner tour de force from Wilhelm Furtwängler

His magnificent wartime recording brought to new life

This 1944 recording would appear to be a live concert performance, broadcast from the Großer Saal at the Musikverein in Vienna and recorded onto tape. I say "would appear to be" not because I doubt the frequently repeated assertions of these facts, but merely because there is no evidence whatsoever of the presence of an audience, something which is also usually noted. I can only assume, therefore, that the orchestra was playing to an empty hall.

Whatever the precise details of its prevenance, this hardly detracts from what many consider to be this work's finest recorded rendition - though some prefer his 1949 BPO Berlin accounts, many find his wartime reading has a little something extra about it which elevates it even higher than his later magnificent readings. Whichever way you lean, however, there's no doubt that this is one of the best ever Bruckner Eighths, and I've worked hard to bring out its full glory in this XR remastering.

The original recording was somewhat uneven - it appears that some of the tape reels were either better recorded in the first place or have survived the test of time better. Hiss levels vary considerably, and the first reel suffers some high-end distortion, heard in loud high brass and string tuttis, which is not present later in the recording - I've tried to control this as much as possible, but one may detect its presence at about 5 minutes into the first movement, and its absence at about ten and a half minutes into the second, where the brass is crisper and cleaner. There was also some minor pitch variation between reels, which I've attempted to even out.

Overall, however, the sonic transformation of the rather cramped 1944 original in this remastering is quite remarkable and dramatic, and gives a much better idea of what the performance must have actually sounded than ever before.

Andrew Rose

BRUCKNER Symphony No. 8 in E major, WAB108

(Edition prepared by Furtwängler based on Haas and earlier editions)

Recorded live at Großer Saal, Musikverein, Vienna, 17th October, 1944

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, November-December 2010

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Furtwängler

Total duration: 78:43

Fanfare Review

One of the great Bruckner recordings of all time

Although there are later Furtwängler-led versions of the Eighth, and superb Furtwangler recordings of other Bruckner symphonies, if I had to live with only a single example of this conductor’s way with Bruckner it would be this one. This performance combines moment-to-moment intensity with an overall sense of architecture and inevitability that carries you through the almost 80 minutes, never really letting the dramatic tension to fall flat even for a moment. Furtwängler’s unique ability to see the interconnections between tempo relationships, dynamic shading and scaling, phrase lengths and shapes, harmonic motion, and orchestral balance and color—to relate each of those elements to each other and to the whole—works to unify Bruckner’s sprawling structure. He also inspires the Vienna Philharmonic to a stunning level of intensity of playing throughout—so that the result is gripping from beginning to end. Furtwängler uses the Haas Edition, of which he conducted the first performance, though he makes a few modifications.

This performance is a classic but many prior transfers have been inadequate, and none as good as this one. The closest to the mark has been, unfortunately, both the hardest to find and the most expensive—a two-disc Japanese EMI set (CD28-5757/58). Most others have been pitched sharp or afflicted by serious flutter, or both. Music & Arts had a very good one (CD-1209) that sounds as if it might have derived from the Japanese EMI. A different Japanese EMI (TOCE 3786) was at the right pitch and with minimal flutter, but somewhat congested and marred by dropouts. All DG and Japanese DG editions of this are sharp and have the flutter problem more seriously present.

Pristine has worked its magic and given us what is probably the best transfer we will get for quite some time, unless someone finds a better original. Some of the flutter that is on the original is still present on long sustained wind notes and chords, but the degree of the problem is minimal and the result will be tolerable for most listeners. More importantly, Andrew Rose has managed a fuller, richer orchestral sonority, one where the bass is firm and strong, as opposed to the bright, hard-edged sound of even the best prior efforts. The result is immediately evident in moment-to-moment A-B comparisons, and is even more compelling over the length of the symphony. Finally one can hear this without the listener fatigue that comes with the excessive harshness of the earlier versions.

The first movement is fierce and rugged throughout. The Scherzo manages to be both massive and light-footed at the same time—a seeming paradox achieved through rich orchestral textures combined with sharply sprung rhythms. The Adagio is the centerpiece that it should be: a longing, yearning performance of which I have never heard the equal. There are slight touches of portamento in the strings that add wondrously to the effect. Bruckner’s finales are generally his most difficult movements for conductors, and this one is no exception. The shape is not clearly constructed, there are many tempo adjustments, and the coda is somewhat brief and lightweight for all that has come before (although it suffers less from this problem than do the Fourth and Seventh symphonies). Here in particular the music gains from the conductor’s ability to see the big picture, to create the necessary tension and release through both tempo and textural adjustments, and to instill conviction in the playing. Furtwängler manages better than most others to hold enough in reserve so as to give a real weight of finality to those last three chords, chords often taken either too quickly or too slowly. The music must move into and through those three chords with logic, and they must produce a sense of climactic ending. Here they do just that.

It is important to note that the sound still does not represent the state of the art even for 1944 broadcasts—but anyone with a tolerance for historic recordings is likely to find it acceptable now, and the performance is a once-in-a-lifetime experience. This is

This article originally appeared in Issue 34:5 (May/June 2011) of Fanfare Magazine.

.

Henry Fogel

This article originally appeared in Issue 34:5 (May/June 2011) of Fanfare Magazine.