This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

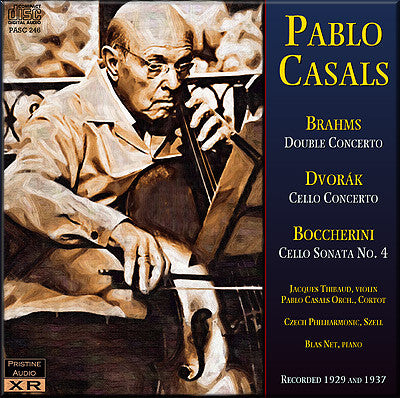

Classic cello recordings from one of the all-time greats

Casals sounds incredibly fresh in these new XR-remastered transfers

The major concerto recordings of Pablo Casals, in particular that of the Dvorák Cello Concerto of 1937, have been staples of the classical catalogue ever since their original releases. At the time of writing there are several issues available in different transfers by different labels, and it is surely fair, therefore, to ask why the world needs yet another transfer.

The truth of the matter is that this release came out of an instance of pure curiosity on my part. I had received, in amongst a major collection of LP records, a vinyl transcription of the Dvorák on a white-label test pressing that appeared to have been barely, if ever, played. I confess I have no idea whether this transfer was released, and if so, when - it was simply to serve as a quick and easy means of subjecting the recording to an XR remastering test - I certainly was not expecting the results of this to merit issue.

However, the LP transfer turned out to be much better than I had expected, and the XR remastering brought such new life to it that I decided to persevere with it, needing only to drop in a couple of short sections from alternative sources where top-end quality was less than excellent. Sitting close by was another test pressing, this time the Boccherini Cello Concerto No 9 with Casals conducting and Maurice Gendron playing. Investigations suggested that this was the first time Boccherini's original - rather than Grützmacher's bastardised version - had been recorded, and that it dated from 1958 but appeared since to have disappeared from the catalogue. I quickly got to work on this stereo recording with the intention of partnering it with the Dvorák, only to discover at the last minute that the erudite and well-respected author of the notes from which I'd taken the recording date was out by a matter of two years, and that the recording itself would remain in copyright until 2012.

Turning - in need of some other recording to add to this release - to the Pristine Audio collection of 78s, I dug out the older recording of Brahm's Double Concerto. As it dates from 1929 my hopes were less high than for the Dvorák, but despite some noisier sides I was extremely impressed with how these came out. The XR process not only opened out upper frequencies and harmonics beyond those normally heard, it also unleashed an unusually rich acoustic from the recording venue which had been somewhat squashed before.

The Double Concerto recording contains clues as to why the XR process can be so successful in reviving older cello recordings - whereas the cello's harmonics are generally quite well represented in the limited frequency range of 1929 recording equipment, there are points where Thibaud's highest harmonics have a tendency to distort and thus produce a less pleasant sound. That said, it's still a remarkably clear and balanced recording for its day, and now far clearer and cleaner than ever before.

Finally, as a result of recent diligent cataloguing work of the darker recesses of our collection by our archivist, I discovered the Boccherini disc tucked away in a large album of mixed 78s and in very good condition. As it was recorded in Barcelona shortly after the Brahms I decided to add it to the concerto recordings as a kind of musical stepping stone between the larger works. Again the remastering process brought out much clarity, warmth and a lovely reverberant acoustic to complement the instruments.

Andrew Rose

-

BRAHMS Double Concerto for Violin and Cello, Op. 102

Jacques Thibaud, violin

Pablo Casals Orchestra

conductor Alfred Cortot

Recorded in Barcelona, 10-11 May, 1929. First issued as HMV DB1311014, matrices CJ2156-63

-

BOCCHERINI Cello Sonata No. 4 in A, G4

Blas Net, piano

Recorded in Barcelona, 16-17 June, 1929. First issued as HMV DB1392, matrices CJ2275-6

-

DVORAK Cello Concerto in B minor, B191

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

conductor George Szell

Recorded in Prague, 28 April, 1937. First issued as HMV DB3288-92, matrices 2HC220-9

Pablo Casals, cello

Transfer & XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, September 2010

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Pablo Casals

Total duration: 75:27

Fanfare Review

Urgently recommended mainly for the Dvořák

Pristine Audio, the love child of audio engineer and restorer par excellence Bob [sic] Rose, is a label dedicated to reclaiming recordings from various sources and, through his proprietary “XR” remastering process, revitalizing them to as “pristine” a state as possible. Sometimes, as it turns out, the realm of the possible falls short of the perfect, and such is the case here with these Casals recordings that have long made the rounds in various issues and transfers on a number of different labels.

The Dvořák concerto as presented here is, for example, not entirely of a piece. Rose explains in his detailed notes that the source for this famous 1937 Casals-Szell team-up was a vinyl transcription on a white-label test pressing that appeared to be in mint condition. Deciding to subject it to his “XR” process, Rose was impressed by the new life it brought to the recording. But the finished product we have on this disc includes “a couple of short sections from alternative sources” that Rose felt compelled to drop in where “top-end quality was less than excellent.” He fails to tell us what those “alternative sources” are, though I suspect they’re other pressings of the same performance, since I’m not aware of another Dvořák concerto from Casals besides this one with Szell.

The Brahms “Double” dates back even further to the 1929 recording Casals made in Barcelona with violinist Jacques Thibaud and Alfred Cortot conducting Casals’ own orchestra. For this “XR” remastering, Rose relied on Pristine Audio’s collection of 78s, stating that “the XR process not only opened out upper frequencies and harmonics beyond those normally heard, it also unleashed an unusually rich acoustic from the recording venue which had been somewhat squashed before.”

The Boccherini sonata, probably the best known and most often recorded of the composer’s sonatas for cello and keyboard, is also taken from vintage 1929 78s, which again according to Rose, revealed “much clarity, warmth, and a lovely reverberant acoustic to complement the instruments,” after undergoing the “XR” treatment.

With due respect, and without meaning in any way to impugn or disparage Rose’s process or his accomplishments, I have to say that there is only so much one can do to resuscitate the Brahms and Boccherini. I’m actually not quite old enough to have experienced the 78 rpm era. By the time I began collecting records in the late 1950s, the 33-1/3 rpm LP had already been around for well over a decade. I’m guessing that by 1929 most, if not all, recordings were being made using the newer electrical, as opposed to the older acoustic, methods. Still, commendable as Rose’s efforts are, there is a constricted boxed-in and covered, blanketed, woolly sound to both of these recordings that makes it more difficult to appreciate some of the subtleties in Casals’ playing, as well as Thibaud’s in the Brahms.

The Dvořák, in contrast, except for some frequency loss at the top and bottom, as well as some dynamic compression, sounds remarkably close to a modern recording. No music critic who wishes to be taken seriously would deny Pablo Casals’ role as the preeminent cellist and perhaps the seminal force in the cello world during the first half of the 20th century. And this recording of the Dvořák is proof of why. It’s simply incredible. Szell and Casals take the first-movement Allegro quite fast—13:33, compared to what became a slower normal of around 15 minutes in 1962 with Starker’s and Doráti’s Mercury recording (15: 08), a timing that persisted into the next generation of cellists with Yo-Yo Ma’s and Masur’s 1995 Sony recording (15: 04). More recently, the tempo has slowed still further with Gautier Capuçon’s and Paavo Järvi’s 2008 Virgin Classics recording (16:20).

But it’s not just Casals’ upbeat tempo; his technique is of virtuosic authority and command, and his tone, even on this recording, emerges full-bodied and refulgent. Nor is there much in the way of the kind of rhapsodic romanticizing one hears in the cellist’s Bach suites where there was no one to ride herd on him. I suspect in this case that Szell, not one to indulge loitering in his soloists, had much to do with moving things along. The result is a performance of enormous thrust and power that, frankly, lends Dvořák’s popular score a much more dramatic slant than it has taken on in more recent soporific readings. Casals lunges at the passage in octaves near the end of the movement with a devil-may-care abandon, and the devil very nearly gets his due, but the cellist manages to sail through it unscathed.

Even the lovely, unhurried lyricism of the Adagio is not drawn out. Compare Casals/Szell at 10:32 to Starker/Doráti at 11:11, Ma/Masur at 12:34, and the almost catatonic Capuçon/Järvi at 12:50. Casals and Szell rout all but one of the others, too, in the finale, romping through it at 11:55. Here Starker and Doráti are actually faster by eight seconds at 11:47, but Ma and Masur take 12:50, and Capuçon and Järvi bring up the rear, limping in lame-legged at 13:18.

I’m not suggesting that there aren’t other versions of the Dvořák concerto worthy of consideration, but Casals and Szell are obligatory for anyone who loves the work and is serious about the cello. While this recording, as mentioned, has long been available in a number of pressings on various labels—EMI, Dutton Laboratories/Vocalion, Pearl, and Opus Kura—I believe Bob Rose has worked his special magic through his “XR” process on this Pristine Audio remastering. Urgently recommended mainly for the Dvořák, though listeners willing to make allowances for the less than ideal sound will also find much to appreciate in the Brahms and Boccherini.

Jerry Dubins

This article originally appeared in Issue 34:6 (July/Aug 2011) of Fanfare Magazine.