This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

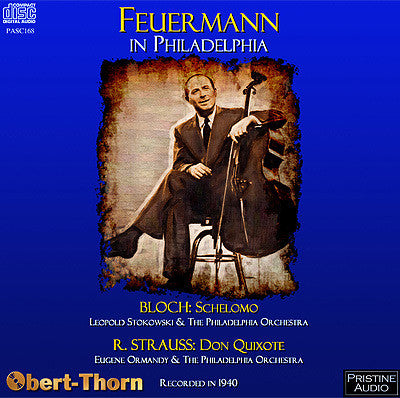

- Cover Art

Feuermann - one of the greatest cellists ever to be recorded

Two magnificant Philadephia recordings - superb transfers by Mark Obert-Thorn

The sources for the transfers were vinyl 78 rpm test pressings for the Bloch (including an unpublished take of the fourth side), and first-edition pre-war U.S. Victor “Gold” label shellacs for the Strauss. These two recordings, along with Feuermann’s December, 1939 recording of the Brahms Double Concerto with Heifetz (Ormandy again conducting) comprise the cellist’s complete recordings with the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

BLOCH: Schelomo

Emanuel Feuermann, cello

Leopold Stokowski / The Philadelphia Orchestra

Recorded 27th March, 1940 in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Matrix nos.: CS 047816-2, 047817-1, 047818-1, 047819-2 and 047820-1

First issued on Victor 17336 through 17338-S in album M-698

-

R. STRAUSS: Don Quixote (Fantastic Variations on a Theme of Knightly Character), Op. 35

Emanuel Feuermann, cello

Samuel Lifschey, solo viola

Alexander Hilsberg, solo violin

Eugene Ormandy / The Philadelphia Orchestra

Recorded 24th February, 1940 in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Matrix nos.: CS 048027-1, 048028-1, 048029-1, 048030-1, 048031-1, 048032-1, 048033-2A, 048034-1, 048035-1 and 048036-1 - First issued on Victor 17529 through 17533 in album M-720

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Emanuel Feuermann

Total duration: 58:08

Fanfare Review

The performance has a kind of sweep and continuity that I can easily see seducing modern listeners

Writing “It’s all over with Germany . . . all over with Europe,” Emanuel Feuermann, who had been a professor at the Berlin Conservatory, joined hundreds of refugees who were able to depart from Nazi Germany, eventually ending up in Austria. He happened to be there at the time of the Anschluss, escaped to Palestine and then, in 1937, to the United States, where he soon found himself making recordings with Jascha Heifetz, Eugene Ormandy, Artur Rubinstein, and Leopold Stokowski. Two of those recordings can be heard on this Pristine Audio CD. These two recordings had previously appeared together on a Biddulph CD during the early 1990s. I thought those CD transfers were very good indeed. One barely noticed the soft hiss of the stylus on the 78s. It is possible that the Biddulph transfer is slightly brighter than this new one on Pristine Audio—here, the surface noise all but vanishes, whether because of different equalization or even better 78-rpm originals, I can’t say. In any case, the Biddulph is, at least temporarily, in limbo and there is now only a 1938 Feuermann/Toscanini live performance of Don Quixote that I have never heard as a possible alternative.

As part of my preparation for this review, I auditioned 11 recordings of Don Quixote and six Schelomos. Of the Don Quixotes, the four fastest (this one, Piatigorsky/Reiner, Uhl/Strauss, Wallenstein/Beecham) were all from the 78 era. Is there some conventional wisdom to be inferred from this? Are performances getting slower and, if so, does this have anything to do with the space restrictions of 78-rpm discs? Is this why some repeats were skipped back then, or was it also the concert-hall custom? The other recordings I listened to were conducted by Munch, Karajan, Kempe (Dresden), Levine, Reiner (Chicago), Slatkin, and Ormandy (his fourth one). As it happens, I find much to admire in all the recordings, but—for what little it may be worth—my favorites turned out to be the three slowest ones: Fournier/Karajan, Janigro/Reiner, and Mayes/Ormandy. Interestingly, Feuermann/Ormandy and Uhl/Strauss, the two fastest performances, both timed out at 38:12, although the Feuermann/Ormandy, perhaps because of its higher energy level, seemed faster than the more subdued Uhl/Strauss recording. Not only is the former a tribute to the kind of 78 transfers we can hear nowadays (it’s the golden age of 78s!), it also testifies to Victor’s mastery of the Academy of Music as a recording venue. It isn’t just Stokowski’s recordings that sound good. Compare Ormandy’s Victor 78s with the dead sound of his early Columbias. There is hardly a significant detail on later recordings of Don Quixote that one can’t hear on this one. The fast tempos do not compromise detail and the performance has a kind of sweep and continuity that I can easily see seducing modern listeners.

There is plenty of energy and animation in the performance of Schelomo, too, even if it isn’t quite as fast as the Zara Nelsova/Maurice Abravanel recording. Her recording with Ansermet is also pretty fast, and I wonder if her tempos were influenced by her first recording of the piece, which was with Bloch himself (which I haven’t heard). As it happens, my favorite Schelomos are the fastest ones, and to Nelsova/Abravanel I would add the two Feuermanns (Leon Barzin and Stokowski). Unfortunately, the Barzin is plagued by some distortion in loud passages, and it’s no better than the impassioned, surging Feuermann/Stokowski performance. Once again, the transfer is splendid. There is no need for the Biddulph, terrific as it is, to be reissued as long as we have this one. By the way, I liked all the other Schelomos, too. They were Neikrug/Stokowski, Rostropovich/Bernstein, and Starker/Mehta (but why wasn’t it coupled on CD with its LP companion, Voice in the Wilderness? The ways of recording companies are truly mysterious).

Not the least of Feuermann’s assets was his gorgeous tone, not necessarily big and fat, but still rich and well focused. He was only 39 when he inexplicably died after an operation to remove hemorrhoids. Among his pallbearers were Mischa Elman, Bronislaw Huberman, Artur Schnabel, Rudolf Serkin, Eugene Ormandy, George Szell, and Arturo Toscanini, who, according to the annotations, broke down and cried, “This is murder.”

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 33:2 (Nov/Dec 2009) of Fanfare Magazine.