This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

We are presenting these recordings in their entirety as recorded, preserving all announcements and applause as broadcast. In some cases there was an interval talk which was not included in our tapes - we have not attempted to source these.

It appears that the original sources for these recordings would have been 33rpm acetate or vinylite radio transcription discs. Surface noise is usually consistent with this, though occasionally there is the suggestion of 78rpm surface swish as well. However, in each case the original sound quality of the orchestra is superb, and it has been a delight for the restorer to work from such excellent quality, full frequency range recordings.

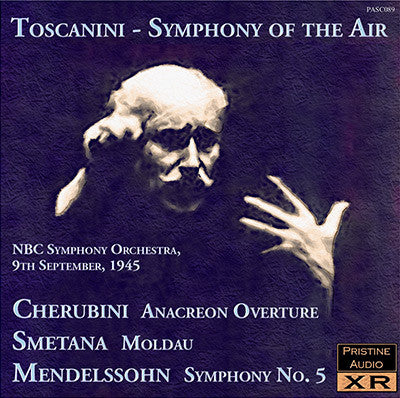

This concert features, as its main work, Mendelssohn's Symphony No. 5, in a fine reading. It was the second of two special concerts broadcast following the end of World War Two - Toscanini's official radio Winter Season of 1945-6 with the NBC Symphony Orchestra began with the concert broadcast on 28th October, 1945 (PASC090).

CHERUBINI Overture to Anacréon

SMETANA The Moldau (No. 2 from 'Ma Vlast')

MENDELSSOHN Symphony No. 5 in D, Op. 107, 'Reformation'

NBC Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Arturo Toscanini

Live NBC broadcast from Studio 8H, New York:

Recorded 9th September, 1945

Presented as broadcast, with studio announcements by Ben Grauer

Pristine Audio XR remastering by Andrew Rose, August 2007

Total duration 53:24

Fanfare Review

I find the overall thrust and immediacy of this 1945 performance more consistently engrossing, compelling, and cumulatively powerful

These releases are a sampling of the Toscanini discs available online from Pristine Audio, which employs a remastering process developed by Pristine’s founder, Andrew Rose, that enhances the sound of the original source materials by using a “harmonic soundprint” (as it were) developed digitally from modern recordings of the music being restored. Of the four discs listed above, the Beethoven Seventh is Toscanini’s famous 1936 recording made with the New York Philharmonic for RCA; the Bruckner Seventh—the only extant example of Toscanini conducting Bruckner—is from a 1935 Philharmonic broadcast; and the two other discs preserve NBC Symphony broadcasts that originated in 1945 and 1946 from Studio 8-H. (Note that in Fanfare 31:4 for March/April 2008, in the postscript to my review of the 1939 Toscanini/NBC Beethoven symphony cycle as issued recently by Music & Arts using this same restoration process, I absentmindedly wrote “a 1935 Bruckner Ninth” where I should have said “Seventh,” referring to this very recording. Having made some detailed comments earlier in that review about the conductor’s 1939 NBC Beethoven Ninth, “Ninth” seemingly got stuck in my head.)

The 1936 Toscanini/Philharmonic Beethoven Seventh (PASC068) requires little comment, the greatness of this recording having gone unquestioned (so far as I can tell) from the time of its original release. I must admit, however, that when I want to hear Toscanini conduct this music, I turn to the 1939 Beethoven Seventh from the aforementioned NBC cycle, if only for its greater immediacy of sound. I should also state up front that I’ve never heard a transfer of the 1936 recording, either on LP or CD, that for me matches the immediacy of the original 78s, which I chanced upon at a yard sale while I was in graduate school. Pristine’s release suffers, at least on my copy, from a persistent layer of static-like graininess (somewhat less noticeable over my speakers than over headphones) whenever the dynamic level reaches or exceeds mezzo forte. As a result, the present restoration strikes me as inferior to the more natural-sounding (if typically “surface-noisy”) transfer issued in 1989 by Pearl (which, like Pristine Audio’s, uses the original, broader version of the first-movement introduction), and inferior also to the 1991 transfer issued by RCA as part of its “Arturo Toscanini Collection,” which, though overly bright, shallow, and bothersomely bass-deficient, at least doesn’t obscure the inner workings of the music.

Interestingly, in his notes for that RCA release, Fanfare colleague/Toscanini authority Mortimer Frank writes that the “second, more propulsive and better-recorded take” of the first-movement introduction was used there “out of respect for Toscanini’s preference for it”; though this begs the question of why the broader version was released to start with, being replaced only after the original master became worn. I have not heard the CD transfer on Naxos, not marketed in the United States, that includes the first movement twice (with both the original and the replacement versions of the first-movement introduction), and which pairs this Beethoven Seventh with a famously powerful 1933 Toscanini/Philharmonic broadcast of Beethoven’s Fifth. That, presumably, is the version to look for. (My 78s, by the way, are of the original release with the slower introduction. Anyone know if they’re valuable?)

For ages, many more Toscanini devotees, including me, have wanted to hear his 1935 Bruckner Seventh with the New York Philharmonic than were ever actually able to do so, but Pristine’s release (PASC082), in astonishingly good sound for the period, should help rectify that situation. Toscanini led the Philharmonic in four performances of the Seventh in March 1931; two performances of the Bruckner Fourth in November 1932; one more of the Fourth in February 1934; and four further performances of the Seventh (the preserved broadcast being the last) in January 1935. With the NBC Symphony he conducted no Bruckner at all. What we have of the Seventh is not quite complete: the first movement is abruptly and frustratingly truncated seven measures before the end; in the Adagio, which is otherwise complete, there’s a three-measure gap about three minutes before the end, at 18: 05 (given the slow tempo, this means about 15–20 seconds of music, presumably the time needed to get a new acetate up and running as the broadcast was being recorded); and in the finale (the Scherzo is complete), there’s a gap of 14 measures at 4:50. If the materials used by Toscanini matched the 1885 score edited by Albert J. Gutmann (the one used by the Boston Symphony back then; Leopold Nowak’s edition for the International Bruckner Society appeared in 1954), he has made a number of alterations to the scoring—including, for example, changes to the timpani part in the first and (possibly) third movements, and the addition of brass (to double the violins) at the start of the finale’s slower-moving “second theme unit”—and has cut that second theme unit entirely in the finale’s recapitulation.

Except for the loss of the first movement’s final page, none of this is overly disturbing. What is disturbing, however, is how uneven the performance is. For interested parties who’ve never heard Toscanini’s Bruckner, the first movement should be revelatory—it’s broad, deeply felt, engrossing in the way one wants Bruckner to be, and suggestive that Toscanini had it in him to be a great Bruckner conductor. But then the Adagio comes off as surprisingly stolid and shapeless (sometimes seeming to proceed measure by measure, or even note by note, with no sense of line or overall architecture—the last thing one would expect of Toscanini!); the Scherzo seems characterless (which it might not have done had the Adagio held up better); and the finale is so rushed that, despite some impressive passages, the main effect is mainly and ultimately one of speed, to no overall purpose. (For what it’s worth, the finale’s tempo designation in the 1885 Gutmann edition is “Bewegt, doch nicht schnell” (italics mine), the same designation printed, in brackets, by Nowak.) Given how inconsistent and surprisingly unsuccessful this performance turns out to be, it’s a pity not to have anything more of Toscanini’s Bruckner, if only to see what might have happened on other occasions. Nevertheless, this is a truly important addition to the conductor’s discography, one that his devotees will unquestionably want to know.

Though departing from my alphabetical headnote order, let me now make reasonably quick work of the 1946 Toscanini/NBC “Manfred program.” (PASC096) The Schumann Overture gets a powerful performance that’s basically identical—except for the sound—to the recording made for RCA in Carnegie Hall the day after the concert. In fact, I actually prefer the more intense immediacy of this Studio 8-H broadcast in Pristine’s remastering to RCA’s Carnegie Hall account. Tchaikovsky’s Manfred Symphony, of which Toscanini was an important advocate, likewise receives an impressively powerful reading—more powerful, I would say, than the other three Toscanini performances on my shelf (his first and last NBC broadcasts of the piece, from December 1940 and January 1953, respectively; and his December 1949 recording for RCA). Yet as much as I can admire it on recordings and in performance, and as interesting as it is to note the conductor’s occasional alterations to the composer’s instrumentation (e.g., the addition of tam-tam to the end of the first movement), this isn’t a piece I’ve ever much cared to hear; and when I do hear it, I want to hear it without the inexcusably disfiguring 118-measure cut that Toscanini imposes on the finale, which completely undermines the narrative and musical structure that Tchaikovsky intended.

Finally we have Toscanini’s 1945 Cherubini/Smetana/Mendelssohn broadcast (PASC089), heard here in excellent sound, in a transfer that retains announcer Ben Grauer’s atmospherically evocative words (however commercially oriented) as to the wartime efforts of the broadcast’s sponsor, General Motors. The opening Anacréon Overture is dramatically taut and engrossing—much preferable to the broader, less-well-controlled 1953 broadcast issued by RCA (in which the slow introduction is more than 20 seconds longer than here), and quite different from Toscanini’s intriguingly loose-limbed, more freely expressive 1935 BBC Symphony performance, which is marked by frequent and sometimes surprising tempo fluctuations. (You can find this on BBC Legends, in the two-disc set that includes the conductor’s 1939 BBC Symphony Missa solemnis.) On the other hand, the rather driven 1945 Moldau on this disc is notably inferior to RCA’s 1950 Carnegie Hall recording, the latter being considerably more spacious and relaxed than what we get here, perhaps due to the time constraints of the hour-long 1945 broadcast, where there’s barely time to breathe between numbers. (Toscanini’s 1953 NBC Moldau broadcast, once available on Memories, is likewise more expansive than the present 1945 account.) But this 1945 account of the “Reformation” Symphony more than makes up for Moldau’s failings. While the 1953 “Reformation” broadcast issued by RCA may be more generally relaxed and atmospheric, I find the overall thrust and immediacy of this 1945 performance more consistently engrossing, compelling, and cumulatively powerful, with a more convincing close than the somewhat more protracted 1953 ending. Toscanini’s tempo for the Allegro maestoso of the last movement, much broader than what’s generally heard—in fact, more maestoso—has been subject to much criticism. But since I first learned the piece from the 1953 broadcast issued by RCA, most other performances I’ve heard tend to strike me as rushed. As it happens, the finale of Toscanini’s November 1942 broadcast (once available on an Arturo Toscanini Recordings Society CD) is closer to what might be considered the “norm” for this music. Taken together, these three performances of the “Reformation” Symphony offer a particularly interesting study in how his approach to a given piece could change over the years, in this case moving from a faster, tighter account to one of increasing breadth—the very opposite of what generalizations pervading the Toscanini literature would lead one to expect. In any event, it’s this 1945 account that I like best of the three, and which to my mind makes this disc particularly recommendable.

Marc Mandel

This article originally appeared in Issue 31:6 (July/Aug 2008) of Fanfare Magazine.