This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

Hot on the heels of last month's opening volume in this collection of previously-unissued recordings made for pianist Vladimir Horowitz by the in-house Carnegie Hall Recording Company onto acetate 78rpm discs, I'm delighted to bring you this second concert, the last of the 1947-48 season, which took place on the evening of Friday 2 April, 1948, exactly two months after the previous concert.

Here the only duplicate from the previous concert is the Schubert Impromptu, once again the second item in the concert; again there's a short, single-movement Scarlatti sonata, and again the concert ended with a Horowitz-enhanced showpiece, in this case an astounding rendition of Sousa's Stars and Stripes Forever.

As with the previous concert the total duration of about an hour and a half leaves it just a few minutes too long for a single CD, but disappointingly short if spread over two discs. As the series progresses we should build up a collection of Horowitz encores sufficient for a CD release of their own - in the meantime if you wish to hear the "extras" - the Sousa, Chopin's Nocturne in F sharp, Op. 15 No. 2 and Mozart's Rondo alla Turca - you'll find them in the free MP3 download which comes when you purchase this CD at Pristine Classical. Naturally our FLAC and MP3 downloads include all tracks.

If anything, the present release exceeds Volume One in terms of sound quality and may well prove the best-preserved of all these concerts, making my job considerably easier than usual. One minor point I should make: the opening 11 bars of the Scarlatti were not captured. By careful editing and the removal of an extraneous note decay, I was able to use the repeat of the opening to replace the missing section. It is interesting to see how incredibly closely and precisely the playing of that repeat matched what we do have of its first incarnation in both timing and nuance - I have little doubt that the playing of the opening bars would likewise have sounded just as it does in the recreation created here.

Andrew Rose

1. BEETHOVEN 32 Variations in C minor, WoO 80 (10:19)

2. SCHUBERT Impromptu in G flat major, Op.90 No.3, D899 (6:42)

MUSSORGSKY Pictures at an Exhibition

3. Promenade (1:30)

4. 1. Gnomus (2:21)

5. Promenade (2nd) (0:49)

6. 2. Il Vecchio Castello (3:29)

7. Promenade (3rd) (0:31)

8. 3. Tuilleries (1:02)

9. 4. Bydlo (2:39)

10. Promenade (4th) (0:38)

11. 5. Ballet de Poussins dans leurs Coques (1:16)

12. 6. Samuel Goldenberg und Schmuyle (2:08)

13. 7. Limoges, Le Marché (1:16)

14. 8. Catacombae (1:11)

15. Con Mortuis in Lingua Mortua (2:30)

16. 9. La Cabane sur des Pattes de Poule (3:04)

17. La Porte des Bohatyrs de Kiev (4:17)

18. CHOPIN Ballade No. 4 in F minor, Op 52 (9:57)

19. DEBUSSY Sérénade à la poupée (No. 3 from Coin des Enfants) (2:56)

20. DEBUSSY Étude pour les huit doigts (No. 6 from Etudes, Livre 1) (1:31)

21. LISZT Funerailles (No. 7 from Harmonies poétiques et religieuses III, S.173) (9:51)

22. RACHMANINOV Prelude in G major, Op.32 No.5 (3:05)

23. RACHMANINOV Prelude in G minor, Op.23 No.5 (3:44)

24. SCARLATTI Sonata in A, K 322, L 483 (2:41)

Encores - Included in downloads only (NB. CD includes MP3 download of these items)

25. MOZART Rondo alla Turca (from Piano Sonata No. 11 in A, K.331)

26. CHOPIN Nocturne in F-sharp major, Op. 15, No. 2

27. SOUSA-HOROWITZ Stars and Stripes Forever

Vladimir Horowitz piano

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

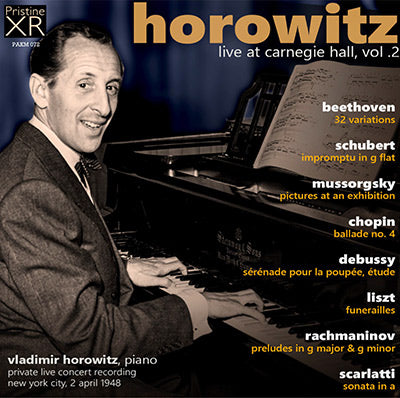

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Vladimir Horowitz

Recorded 2 April1948

Carnegie Hall, New York City

Total duration: 79:27 (CD) & 91:23 (Download)

Fanfare Review

Don’t hesitate: These are exceptional, even transcendent, releases

Starting in 1995, RCA sporadically issued a series of discs containing previously unreleased excerpts from a dozen or so concerts given by Vladimir Horowitz between 1945 and 1950. That material later reappeared, although differently organized, in Sony’s huge 42-disc Horowitz at Carnegie Hall box. Now Pristine has offered us the entirety of two of those concerts—minus most of the encores (more on that later)—giving us nearly two hours of Horowitz performances that are apparently new to the catalog.

So, how are they? In his interview in Fanfare 41:3, Pavel Gintov described Horowitz as follows: “There are artists who are very egocentric and still great: Vladimir Horowitz is one of those. He really wants to be the center of attention. You can hear him present in all music that he plays.…I don’t want to sound like I’m criticizing him. I love Horowitz, I’m just trying to say that you can always hear him playing himself. When he plays Beethoven he plays himself and when he plays Scarlatti or when he plays Chopin, he plays himself.”

If the description is hyperbolic, it’s only slightly hyperbolic, and it certainly applies to the interpretations here, where Horowitz is consistently playing himself. But what a himself! From first note to last, these are astonishing performances, and while purists and the faint of heart might find it all too much, other pianophiles will probably be transfixed. I’m not sure whether or not Horowitz reached his peak in the late 1940s, but listening to these discs will probably persuade you that he did.

Horowitz, of course, is often described (sometimes with a sneer) as a barn-burner, and there is plenty of incendiary playing here, not only in “The Great Gate of Kiev” and in the truly terrifying left-hand-octave climax of Funérailles, but in the climaxes of the Chopin First Ballade and elsewhere as well. But for every moment of unparalleled thunder, there are half a dozen others where the pianist draws the most delicate sounds from the instrument. In the ending of the first movement of the Kabalevsky Third Sonata, for instance, or the ending of the Chopin First Impromptu, there are sounds few other pianists could match. But there’s a lot more than his handling of extremes (which would have to include, besides the extremes of dynamics, his often radical rubato as well). For instance, there’s the exceptional voicing that draws unfamiliar lines from the texture, in some cases (like the first movement of the Kabalevsky) making the music sound more interesting that it really is. Then, there’s the variety of articulation. As his performance of the Chopin Fantasie makes clear, he can be not only as sharp as anyone, but also as luxurious, and the shifts from one to the other (and to numerous stages in between) keep you consistently alert. There are moments of seductive charm, too (the gracious curl of the opening of the Kabalevsky, the Scriabin Poem). There’s tremendous wit here as well, not only in the surprises that dot his extremely pianistic reading of the Haydn Sonata, but also in the giddiness of the outer sections of the Chopin Impromptu and in the ending of the Debussy Étude.

In the end, the most striking general quality is the consistent eventfulness of the performances. And nowhere is this as evident as it is in this reading of his notorious edition of Mussorgsky’s Pictures. As a teenager, under the thrall of Richter, I thought of Horowitz’s Pictures (which I knew from his studio account) as bangy. But while there certainly is plenty of sheer spectacle (and not only in the four-hand illusion of the final measures), this 1948 recording is equally notable for its interpretive invention: have the unborn chicks ever danced with more wit? Indeed, few pianists differentiate among the pictures quite as dramatically as Horowitz does. This reading, arguably even closer to the edge than his studio version or even his 1951 Carnegie Hall taping, hasn’t quite dislodged my loyalty to the Richter, but I surely wouldn’t want to be without it.

As for the encores: Pristine includes a slightly edited version of the Scarlatti Sonata that served as the first encore of the second concert (the opening measures were missing and had to be spliced from their reappearance later on), but the rest of the encores (including scorching readings of Horowitz’s version of Stars and Stripes Forever from the first concert and his Variations on the Mendelssohn Wedding March from the second) couldn’t be fit onto the already generous discs. They are included in the downloadable equivalents of these releases on the Pristine site and as free bonuses to people who buy the CDs—except in the United States, where a copyright spat has blocked all downloads of this material. Since they’re made in and shipped from France, however, the physical discs can still be purchased stateside, something that I’d urgently recommend, especially since the Sony set (and most of the RCA material) is currently hard to find, at least in CD format. The notes, as usual for Pristine, are minimal; but Andrew Rose seems to have drawn excellent sound from his sources. Don’t hesitate: These are exceptional, even transcendent, releases.

Peter J. Rabinowitz