This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

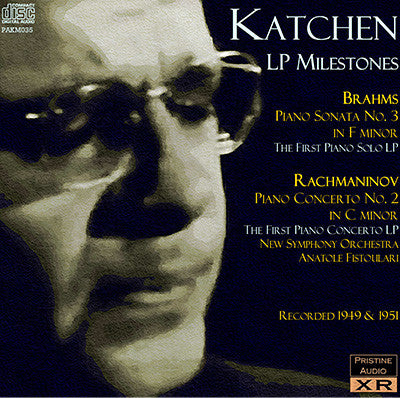

Groundbreaking LP releases from the great virtuoso Katchen

The first solo piano & piano concerto LPs - now in exceptional XR remasters

Both of these recordings represent true milestones in the development of the long playing record. The Brahms was originally released in the USA by Decca's American subsidiary, London, some seven months prior to Decca's launch of the LP format in the UK in June 1950, when this LP was amongst the first batch of issues. Although the long player had been around in the States for some two years, Katchen's LP release of the Brahms 3rd Piano Sonata was in fact the first full LP of music for solo piano.

A year later, the pianist notched up a second historic first - astonishingly, the Rachmaninov 2nd Concerto recording he made with Fistoulari just two months prior to its June release was the first piano concerto release on LP. Both this and the Brahms are worthy holders of these titles - Katchen is still today remembered perhaps more than anything for his playing of Brahms, and although the 3rd Sonata was not his earliest recording of Brahms for Decca, it was the first to see commercial release:; in May 1947 Katchen had recorded the Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel in a session which aslo saw the recording of his first actual Decca disc release (Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody was issued on 78rpm in February 1948). This first Brahms recording has remained unissued, along with two other recordings from this session, and it was remade in a recording done in April 1949 and issued first on 78rpm in September 1950 and eventually on vinyl in 1952.

This was clearly a confusing time for the record buyer. During the sessions that yielded the 3rd Sonata, Katchen had also recorded Brahms' Intermezzo in E flat Op.117/1, but this was only ever issued on 78s - in a set which paired it with the Third Sonata (AX423-27) when issued on shellac nine months after the sonata's vinyl release! The same sessions resulted in three Chopin recordings which again would have needed to be collected on both vinyl and shellac by the 1950's Katchen completist.

By April 1951 things seem a little more settled, format-wise. The Rachmaninov was still issued on both 33rpm and 78rpm, but this time the vinyl and shellac release dates were just a month apart (possibly less - we only have the month to go on and not the precise issue date), with UK vinyl getting the priority over both shellac and the US vinyl release.

Both of the sessions represented here were produced by the legendary John Culshaw, with the equally revered Kenneth Wilkinson manning the controls for the Concerto recording (we have no record of who engineered the Sonata), and both live up to the standards one comes to expect from Decca at this time. What is unusual about both, but was clearer to me when restoring the Sonata, is a rather unusual harmonic distortion that was evident during louder sections at the frequency range above about 8kHz. However, the trigger for this distortion is not the higher notes - these are generally clean and clear when heard in isolation - but rather the lower notes in the left hand. Booming bass notes seemed to trigger a high end distortion which subsequent research strongly suggests was a product of the tape recorders in use at the time, rather than the vinyl replay medium.

Consequently much of the time spend remastering these otherwise excellent recordings has revolved around taming this tendency where it occurs. Both recordings have emerged from the XR remastering process sounding truly rejuvenated, and although sharper listeners with highly analytical hi-fi systems, listening at higher volumes, may still be aware of some residual traces of this distortion in the Sonata, for the majority it will be merely a curiousity to be read about and not heard. Certainly my own hi-fi speakers don't reproduce it noticeably at normal listening levels.

From a performance point of view it is clear why Katchen was to be associated with Brahms so much - this early recording is really excellent. Writing in The Gramophone in July 1950, L.S. has the following to say:

Julius Katchen gives an impressive performance which has real coherence (he is, of course, helped by L.P. continuity): he seems equally successful with the massive highly-strung style of the opening (how alike in feeling this is to the 'D minor Concerto, written a year later!) and the sentimental ardours of the slow movement (which is prefixed by three lines from a love poem by Sternau). In the Scherzo, with its flying leaps, Katchen manages to keep the movement light and airy at the same time as giving it substance: in fact, the only criticism I have to offer of this very considerable pianist is that he is inclined to overdo the left-hand-before-right-hand trick to express deep feeling.

The Rachmaninov's reviewer H.F., in August 1951, managed to get himself somewhat amusingly tangled up in the new-fangled vinyl technology:

Long-playing records are almost as moody and unaccountable as composers. No amount of flattery, persuasion, and tactful handling will make this one play ball with me (perhaps out of an innate psychological sense of revenge that I am not a whole-hearted admirer of Rachmaninov as a composer ?). The tonal range is wide enough; but when I turned things down so as to reach a tolerably pleasing all-over sound, there was no body left; as soon as I began to turn things up, the effect was increasingly as if the music had been recorded in a biscuit tin...

...before delivering a verdict which turns to the performance itself (suffice to say his concerns about sonics are not evident on this new Pristine XR issue):

This is the pianist's recording—he takes it by his powers (which are high) and is allowed it by those who balanced orchestra and solo instrument. Memory is a trickster, but I fancy Rachmaninov himself played the Concerto with greater warmth, more lovingly, less athletically. In other ways Julius Katchen is a worthy follower of that great performer. I feel that the performance as a whole design laid out before one suffers a little from the fact (as it seems to me) that the pauses are each slightly too long for gramophone reception. The piano tone is consistently far better than the orchestral tone, despite an occasional point of blasting. The pianist shows himself at his best in the third movement ; but, indeed, he is exceptionally good all the way through.

Andrew Rose

-

BRAHMS Sonata for Piano No. 3 in F minor, Op. 5

Julius Katchen, piano

Recorded 11 October 1949, West Hampstead Studios, London, produced by John Culshaw

Issued on LP in the USA Dec. 1949 as London LLP112 and in the UK in June 1950 as Decca LX4012

Also issued in the UK as Decca 78s AX423-27 in March 1951

-

RACHMANINOV Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18

Julius Katchen, piano

The New Symphony Orchestra

conductor Anatole Fistoulari

Recorded 11-12 April, 1951, Kingsway Hall, London, produced by John Culshaw, engineered by Kenneth Wilkinson

Issued on LP in the UK in June 1951 as Decca LXT2595 and in the USA in July 1951 as London LLP384

Also issued in the UK as Decca 78s AX535-39 in July 1951

Transfers and XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, March 2010

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Julius Katchen

Total duration: 64:28