This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Sleevenotes

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

Siegfried is perhaps the least respected of all the Ring operas. Some say it lacks the taut drama of Das Rheingold, the intensely personal emotions of Die Walküre or the spectacle of Götterdämmerung. In some respects, it could be classified as a chamber opera – the whole of Act 1 takes place in Mime’s cave, the whole of Act 2 outside Fafner’s cave, and only in Act 3 is there a (small) scene change from near Brünnhilde’s rock to its summit. It’s also a peculiarly male-dominated opera. It’s hard to think of any other opera where all the singers in Act 1 are male, and indeed for large parts of it, only tenors are singing. Female voices are not heard until the latter stages of Act 2, and only given real prominence for the final half an hour of Act 3. Yet for all these reservations, Siegfried is a masterful opera.

The story introduces us to Siegfried, love-child of the ill-fated Siegmund and Sieglinde from Die Walküre. He has been raised, after the death of his parents, by Mime the Nibelung dwarf, brother of Alberich, and last seen in Das Rheingold. In Act 1, Siegfried learns of his parentage and successfully re-forges Nothung, the sword shattered by Wotan in Die Walküre. In Act 2 Siegfried kills Fafner, who has turned himself into a dragon to protect the gold. This is done at Mime’s urging, as he wants the magical treasure for himself. Tasting a drop of Fafner’s blood enables Siegfried to understand the voice of a Woodbird, who warns him to beware Mime’s duplicity and Siegfried quickly slays him. The Woodbird then tells Siegfried of a heroine fit for a hero, sleeping on a rock, surrounded by magic fire, and Siegfried sets off to claim his bride. In Act 3, Wotan, disguised as the Wanderer, tries to block Siegfried’s path, but the newly forged Nothung shatters Wotan’s spear and Siegfried passes through the fire. At the top of the rock he awakens Brünnhilde and they sing a rapturous love duet. At its heart Siegfried shows us the transformation of a boy into a man, but it also marks the liberation of mankind from divine meddling.

The title role in Siegfried is incredibly difficult to cast. The part is perhaps the longest tenor role in all opera, and the character is on stage for most of each act. The number of tenors who have been able to sing the part successfully is vanishingly small. The voice has to be large and heroic – easily distinguished from Mime - yet light and versatile at the same time as there is a lot of quiet, reflective singing in Act 2. Above all, the tenor must have stamina. It is a cruel trick to put a vocally demanding love duet at the end of a four-hour opera with a soprano who has only just woken up. There are plenty of Siegfrieds who have little voice left by the end of Act 3 and are dominated by a Wagnerian soprano who is really just getting warmed up. Hans Hopf offers us a Siegfried that ticks many of the right boxes. His voice is large and carries a certain heft that the role demands. He also possesses that rare stamina that enables him to sing this role successfully. He sounds just as fresh in Act 3 as he did in Act 1. It would be unfair to compare him to the matchless Lauritz Melchior, heard in the role on the 1937 broadcast from the Met (PACO139), and instead we should measure Hopf against Wolfgang Windgassen, his great contemporary. Hopf has more stamina and vocal weight while Windgassen is the more thoughtful singer. Only Hopf disrupted Windgassen’s reign as the Siegfried at Bayreuth between 1953-67, assuming the role between 1960 and 1964. He also sang Walther, Tannhauser and Parsifal at both Bayreuth and the Met, but sang Lohengrin only at the latter.

Paul Kuen and George London return as Mime and Wotan/Wanderer from Das Rheingold. Kuen was a master of the role, performing it at Bayreuth and elsewhere, and he gives us a truly sung characterisation rather than the caricature that others sometimes offer. London is here singing his first Wanderer but he has the role well under control, offering both gravitas and wit. Birgit Nilsson resumes her role as Brünnhilde, and compared to Die Walküre and Götterdämmerung, this is almost a day of rest for her. Her brief appearance is thrilling and her trademark high notes, including a magnificent final high C, don’t disappoint. As in Das Rheingold, Jean Madeira gives us a powerful and authoritative Erda while Fafner is sung by Gottlob Frick, one of best Wagnerian basses of the 1950s and 1960s. Most of Frick’s career was in Europe, indeed he sang only twelve performances at the Met, but he was the Hunding and Hagen at Bayreuth between 1960 and 1964 and sang both roles in Decca’s Ring Cycle under Solti.

Erich Leinsdorf continues his policy of performing the Ring uncut, and this is the first ever Met broadcast of Siegfried without the customary cuts in Act 3.

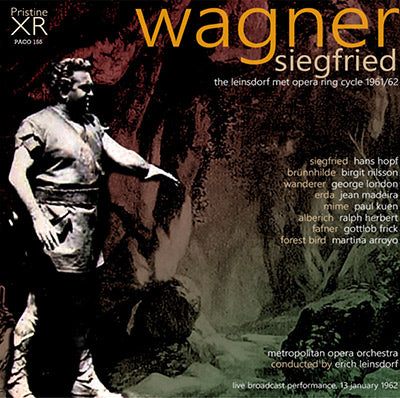

WAGNER Der Ring Des Nibelungen: 3. Siegfried

CAST

Siegfried - Hans Hopf

Brünnhilde - Birgit Nilsson

Wanderer - George London

Erda - Jean Madeira

Mime - Paul Kuen

Alberich - Ralph Herbert

Fafner - Gottlob Frick

Forest Bird - Martina Arroyo

conducted by Erich Leinsdorf

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Hans Hopf as Siegfried against a detail from Josef Hoffman's 1876 set designs

Live broadcast from New York Metropolitan Opera House, 13 January, 1962

Total duration: 3hr 49:17

Opera duration: 3hr 45:06

Review of Robert Sabin in Musical America

This uncut "Siegfried" was full of delightful discoveries. I can offer Erich Leinsdorf no higher praise than to say that the beautiful playing of the orchestra brought back may vivid memories of Fritz Stiedry's inspired interpretation of this score. Nowhere was Wagner's miraculous sense of color and atmosphere more subtly employed than in this music, which stirs the intellect as it intoxicates the senses.

All of the members of the cast were new to their roles at the Metropolitan, except Miss Madeira and Mr. Herbert, and all of them were excellent. Mr. Hopf could not, in the nature of things, look like a young hero, but he sang and acted like one, with a full understanding of his marvelous musical opportunities. The pathos of the orphaned boy, his horror of evil and his need for love were very real to this fine singer and artist.

It needed no more than the awakening to stamp Miss Nilsson's Siegfried Brünnhilde as one of the great ones of all time. The plastique was memorably beautiful and her tones poured forth with a freshness, gleam and abundance that kept one tingling with amazement. Her final high C, instead of an agonized effort, was a rapturous outburst. Like Mr. Hopf, she was aware every second of what she was singing about, and it is a sad commentary on Wagnerian standards that I should have to single this as a rare virtue.

Another memorable performance was that of George London. Not since Friedrich Schorr have we had a Wanderer who brought to this role such majesty of bearing, beauty of voice and diction, and dramatic profundity.

Paul Kuen was an ideal Mime and managed to sing the role, instead of barking it, and he combined grotesque malevolence with a sort of cringing pathos in his portrait of a creature that was neither all man nor all monster. His facial expressions alone were marvels of distortion and characterization.

Gottlob Frick, great artist that he is brought out the sleepy heaviness of the rather lovable dragon and the marvelous irony of "ich schlafe and besitze" ("I sleep and I own"). And Martina Arroyo sang the exquisite music of the Forest Bird with startling volume but saving agility and gracefulness.

Miss Madeira had the right kind of voice for Erda, but she had her troubles with placement and phrasing at this performance. Mr. Herbert helped to make the quarrel between Alberich and Mime (one of the wittiest things in all music) one of the highlights of a generally eloquent performance.

[Review of performance of January 2, 1962]