This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

- Sleevenotes

- Contemporary Reviews

As Gramophone magazine explain, this classic matinee performance of Rigoletto is rightly regarded as one of the greatest ever recorded:

"This performance marked the return of Bjorling to the Met after a

wartime break of four years spent mostly in his native Sweden. And what a

return: at 34 he was at the absolute peak of his powers and sings a

Duke of Mantua imbued with supreme confidence and tremendous brio – try

the start of the Quartet to hear what I mean. He and the house revel in

his display of tenor strength, yet that power is always tempered by

innate artistry. If not a subtle interpreter, he is always a thoughtful

one, and never indulges himself or his audience.

Similarly, Warren was at the time at the zenith of his career. Vocally he is in total command of the role and the house. His reading, though slightly extroverted, evinces a firm tone, a secure line and many shades of colour. He is at his very best in his two duets with Gilda (sadly and heinously cut about) and no wonder, given the beautiful, plangent singing of Sayao, whose ‘Care nome’ is so delicately phrased, touching and keenly articulated. ‘Tutte le feste’ is still better, prompting Paul Jackson (who in general is unjustifiably hard on the performance in Saturday Afternoons at the old Met, Duckworth: 1992) to comment that Sayao’s ‘lovely, pliant, fully rounded tones are immediately affecting’. Indeed, in spite of the merits of the two male principals, it is her truly memorable interpretation that makes this set essential listening.

All round, there are few recordings that match this one for vocal distinction – perhaps only the Serafin/Callas/Gobbi on EMI (2/56R) and the Giulini/Cotrubas/Cappuccilli on DG (11/85). They are much more expensive but, of course, boast superior sound (there are moments of distortion here, though not too many). Bjorling and Warren both made later studio sets, but neither matches his live contribution here, off the stage."

I had four different source recordings to work from, the best of which was an open-reel copy of the original broadcast, including some of the radio announcements. what do survive I have included as much as possible.

The source wasn't perfect, however. Significant work was required, particularly in the last act, to correct pitch problems that had caused a gradual lowering of almost a complete tone across the end of the act. Elsewhere wow was also an issue that I've resolved as much as possible. The tape also suffered several gaps, some more obvious than others, and these have been patched from the other sources and blended to appear seamless to the listener.

I should at this point state that none of the other sources was perfect either - each had its own flaws. However the overall sound quality from the tape reels gave them a clear edge over my other options. The frequency range here is limited to about 8kHz, and whilst voices are clear throughout and the balance with the orchestra well managed it will never resemble a true high fidelity recording. My role was to squeeze as much as possible out of what was available to me and to improve on previous issues, something I hope I've achieved.

Andrew Rose

VERDI Rigoletto

CAST

Rigoletto - Leonard Warren

Gilda - Bidú Sayão

Duke of Mantua - Jussi Björling

Maddalena - Martha Lipton

Sparafucile - Norman Cordon

Monterone - William Hargrave

Borsa - Richard Manning

Marullo - George Cehanovsky

Count Ceprano - John Baker

Countess Ceprano - Maxine Stellman

Giovanna - Thelma Altman

Page - Thelma Altman

Orchestra & Chorus of the Metropolitan Opera

conducted by Cesare Sodero

Matinee performance of 29 December 1945

Metropolitan Opera House, New York City

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

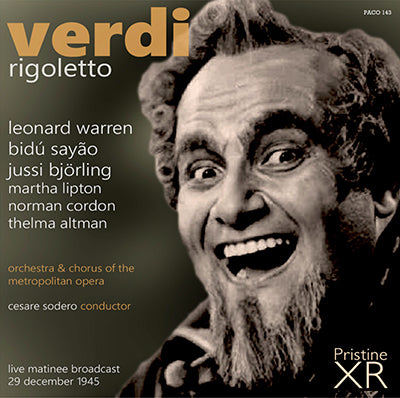

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Leonard Warren as Rigoletto

Total duration: 1hr 58:51

Jussi Björling and Leonard Warren shared a remarkably similar career path. Both were born in 1911, Björling in Borlänge, Sweden and Warren a couple of months later in New York. Both had the major part of their careers at the Metropolitan Opera House, Björling making his debut in November 1938, Warren in January 1939. Warren died on stage at the Met during a performance of La Forza del Destino in March 1960, Björling died at home in Sweden a few months later. Neither reached fifty years old. Although it is tempting to muse on opportunities lost and roles never sung, it is better to focus on what both artists achieved both individually and together.

Warren appeared at the Met more than 600 times in his 21-year career, but was partnered with Björling only twenty-six times. He was heard as Rigoletto by the radio audience in nine matinee broadcasts between 1943 and 1959, but this is the only one with Björling. Warren was, without doubt, the supreme Verdi baritone of his generation. His warm, velvet voice was capable of conveying subtleties of emotion and had the power to reach to the back of the Old Met with ease. His high notes, and Verdi wrote plenty, were unstrained and he could reach a high G or even A-flat without ever losing the baritonal grounding of his voice. His portrayal of Rigoletto focused on the paternal relationship with Gilda, and less on the court jester. He recorded the role commercially with RCA in 1950.

Jussi Björling’s last Met performance before the war had been in Rigoletto on 27 February 1941. He spent the next four years in his native Sweden and his first Met performance on his return, on 29 November 1945 was once again Rigoletto. Björling was 34 in 1945, and although he recorded the opera commercially in 1956 with Robert Merrill in the title role, this broadcast captures him as the ideal Duke with the added excitement of a live performance. His bright youthful tone seems just right for the Duke’s callous playboy image, and his arias in the first and last acts are wonderfully carefree.

Gilda is sung by Brazilian soprano Bidú Sayão. Sayão was older than both Warren and Björling and would live to be 96. She made her major international name as a lyric-coloratura soprano in Milan and Paris in the early 1930s before arriving in the US in 1935. Sayão sang at the Met between 1937 and 1952, most notably as Massenet’s Manon, Mimì in La Bohème and Susanna in Le Nozze di Figaro and was heard on matinee broadcasts thirty-seven times. She only sang Gilda on seven occasions at the Met, two of which were broadcast, but judging from this broadcast she had a touching vulnerability that was well-suited to the role. She would partner Björling in broadcasts of La Bohème and Roméo et Juliette but the only other broadcast with Warren was a 1943 La Traviata.

Italian-born Cesare Sodero conducts the opera. Sodero had come to the US in 1906 as a twenty-year-old and spent most of his career conducting opera and concerts on the radio. In 1942 he joined the conducting staff the Met and would conduct more than two hundred performances before his death in 1947.

OPENING NIGHT REVIEWS - 29 NOVEMBER 1945

Review of Noel Straus in The New York Times

'RIGOLETTO' GIVEN AT METROPOLITAN

Björling Returns After 4-Year Absence - Warren Sings Title Role, Bidu

Sayao is Gilda

Verdi's "Rigoletto," the first Italian work presented this season at

the. Metropolitan Opera House, received a performance that aroused

fervent enthusiasm from the large audience gathered to hear this

ever-popular masterpiece. Jussi Björling, the Swedish tenor, who

returned recently to this country after a four-year absence, made his

reappearance with the company at this presentation, and special

interest centered in his portrayal of the Duke.

This role was not one in which Mr. Björling was particularly well cast

and failed to set forth his gifts in the brightest light. It demands a

graceful, suave type of approach less congenial to his temperament than

parts asking a more robust and vigorous style. He could bring warmth

and vibrancy to his delivery of the music, but not a sufficient degree

of the elegance and finesse that are its prime requisites.

The deficiency was at once noticed in the tenor's treatment of his

[first] aria, "Questa o quella," and again in the "Parmi veder le

lagrime." Both were too heavily projected to convey the essential

characteristics of the nobleman's nature as Verdi has depicted them in

these solos.

Voice Retains Volume

Mr. Björling's tones had lost none of their volume since last heard

here, but last night there was less velvetness to the voice than of

old, and the top had a wiry quality not formerly in evidence. But he

must be heard in a role more suited to him before his present vocal

state can be fully judged, one in which he can more legitimately employ

the upper register in the full-throated manner he used too often in

this opera.

In the title role Mr. Warren showed a definite step forward in his

interpretation. This was markedly the case in the first two acts, which

had gained in dramatic intensity and vividness of detail. The duet with

Gilda in the second act evinced a far deeper feeling of tenderness and

paternal affection than in the past and the fluctuating moods of the

"Pari siamo" outburst were handled with a new skill.

At its best Mr. Warren's singing was remarkable in its tonal richness

and solidity. But there were times when it became breathy, as in the

second half of the "Cortigiani" aria, which did not match the first

half either tonally or in effectiveness of interpretation. The first

half had great power and appeal and in it, as in most of the rest of

his work, there was definite strength and conviction.

Miss Sayao the Heroine

Miss Sayao sang with her usual skill and expressiveness as Gilda. But

the role makes too great demands on her light voice. The "Caro nome"

was admirably clean and secure in its every phrase, but could not

achieve real brilliance, nor was it possible for the artist to lend her

tones the weightiness wanted for such an outburst as the final duet of

the third act.

The Monterone of William Hargrave was vocally acceptable, although his

voice, too, was not big enough to lend his malediction of the jester in

the first act its full need of impressiveness. All the other roles were

in capable hands. Notably the Sparafucile, Nicola Moscona, who made

much of his first and most important contribution. The performance

moved along smoothly under Mr. Sodero's direction.

Review of Robert Bagar in the World-Telegram

Jussi Bjoerling Returns with "Rigoletto" at Met

The return of Jussi Bjoerling, Swedish tenor, after an absence of four

years was a provocative aspect of last night's "Rigoletto" at the

Metropolitan. Mr. Bjoerling, it was quite plain, has lost none of his

freedom in singing. His voice is a mite less luscious than formerly,

though he let out beautiful tones many times during the evening. But

the effortless quality of his work was again a major attribute of it.

It may be that the Duke of Mantua is not entirely in his grasp at the

moment. For some of the subtler sides of the part escaped him - and,

naturally, the listener. However, his delivery of "Parmi veder le

lagrime" in Act III and some of the music in the previous scene added

up to as fine a bel canto style as you'll hear at the Metropolitan this

season. And maybe better.

At any rate, Mr. Bjoerling's Duke is a boyish, prankish philanderer,

and who finds the chaos more absorbing than consummation, or

thereabouts. And the unwonted energy of his singing, the spontaneous

quality, the warmth, provided compensation enough for any lacks.

Miss Sayao as Gilda

A familiar Gilda appeared in the person of Bidu Sayao. And like before,

Miss Sayao artfully built up the character of the young girl as the

opera wore on, until suddenly one realized she had been a true Gilda

all the while. Her coloratura was precise and believable as something

symbolizing very young youth. Her voice , not always at its best, she

firmly controlled. Of course, she sang "Caro nome" very musically, and

it was all pleasing and enjoyable to hear, even if she chose to forgo

the high E at the end, as well as the traditional passage leading up to

it.

In the way "La Traviata" is Violetta's opera, "Rigoletto" virtually

belongs to the tragic jester. So Leonard Warren, disclosing an

improved, dramatically mature characterization, took the proceedings

away from his colleagues. In the first place, he was generous, but not

extravagant with the gold that lies in his tones. He used the voice

mostly as an interpretive medium, and in so doing got right down to

fundamentals.

There were some exciting contrasts in "Pari siamo" that he had never

made before, and with time he'll be sure to make them all. If Mr.

Warren had not been tempted to hold the [first] note of "Ah, si

vendetta!" too long, the song would have had more effect.

One of the special pleasures of the evening was Nicola Moscona's

Sparafucile, an impersonation whose villainy eluded no one, nor whose

musical side could be questioned. Also worthy, operatically speaking,

were the efforts of William Hargrave, the Monterone; Alessio de Paolis,

the Borsa; and George Cehanovsky, the Maurillo.

It would have added a lot in the Quartet to hear Martha Lipton sing out

the "Ha ha's," which, by the way, comprise the anchorage of the piece.

As she did them, weakly and casually, that number lost a good deal of

the four-square solidity it is supposed to possess. Otherwise she was

an acceptable Maddalena. The cast also held Thelma Altman, Giovanna;

John Baker, Ceprano; Maxine Stellman, the Countess; and Miss Altman,

again, the Page.

As a whole the performance was commendable for its drive, constant

fluency and frequent scintillating moments, all of which were owing to

the masterly conducting of Cesare Sodero. With him in the pit Verdi's

melodies always avoid the barrel-organ conventionality that they seem

to get in some other hands. And furthermore, he conducts the work as a

complete thing and not as a series of ear-wooing episodes.

There was a huge audience and, you've guessed it, a highly enthusiastic

one.

Fanfare Review

This one from the Met has to be counted as one of the very greatest, and Pristine has given it its best treatment to date

The performance itself represents one of those afternoons on a Saturday from the Met where the entire cast was on, and everyone seemed to be inspiring everyone else. Too bad that the great Ettore Panizza had left the Met’s conducting roster in 1942, as the rather routine conducting of Cesare Sodero is the only limiting factor here. Sodero is by no means awful—he just lacks that final degree of white heat and variety of inflection that Panizza brought to his Verdi at the Met between 1934 and 1942. Some of the minor comprimario roles are no better than adequate. Yet where it counts, this performance has nothing but remarkable singers.

In the title role, Leonard Warren is triumphant. Warren’s magnificent rich baritone was so special that it is easy to forget that he was also an intelligent and caring vocal actor. This was always more true of his staged performances than his studio recordings. He takes risks onstage that he doesn’t on disc. The wonderful decrescendo as Warren begins “Si, vendetta” perfectly depicts the build-up of fury in Rigoletto as the full weight of what has happened to his daughter settles in. The snarling tone he brings to “Pari siamo” and the note of horror as Rigoletto first learns of Gilda’s kidnapping—all of these moments are vividly conveyed with a dramatic specificity that few baritones could muster. At the same time, the voice is the Verdi baritone of one’s dreams. It rings out all the way up to the top; it is even throughout the range; and when Warren sings softly his voice retains its fullness of tone. If you only know Warren’s Rigoletto from his RCA studio recording, you really don’t know it at all. This is a far more completely characterized rendering of the role, which can be described in a single word, overwhelming.

Even more of an improvement over the RCA studio recording is the Duke of Jussi Björling. RCA’s Jan Peerce sang with keen musicianship but a monochromatic and rather nasal timbre. Björling, again showing more dramatic involvement than he did on studio recordings, is as good as it gets as the Duke. His shaping of the music (listen to the opening of the Quartet for a model in Verdi phrasing), his outpouring of glorious tone, the vocal beauty in his seduction of Gilda (her succumbing is quite understandable)—all of these are examples of the art of operating singing at its highest.

The Brazilian soprano Bidú Sayão was a Met audience favorite for 15 seasons (1937–1952), and one can understand why. Her silvery voice, sensitive dramatic instincts, impeccable intonation, and limpid phrasing all served her well in a wide range of repertoire: Mozart, Massenet, Gounod, Puccini, Verdi, and of course Villa-Lobos. Sayão’s is among the most beautifully sung Gildas on disc, and as with the men, dramatic interactions that come more strongly in staged performances give her performance real urgency. Sayão may not match the remarkable imagination of Callas’s EMI recording, but she surprises with the requisite coloratura technique in “Caro nome,” which is the equal of any other recorded Gilda. In secondary roles Norman Cordon’s black basso is effective for Sparafucile, and Martha Lipton is a well-above-average Maddalena. Some of the smaller roles are no better than adequate, but none of this really matters. The performance utilizes the traditional cuts of the period.

Rigoletto has received many fine recordings, starting in 1930 with Riccardo Stracciari’s classic La Scala set. This one from the Met has to be counted as one of the very greatest, and Pristine has given it its best treatment to date. A few snippets of Milton Cross’s broadcast announcements are included, bringing back lovely memories from my youth. Pristine provides a minimal program note, which makes the interesting point that Warren was born a couple of months after Björling, in 1911, and the tenor died a few months after Warren’s dramatic onstage death in 1960, both of them before their 50th birthdays. I hadn’t really focused on that fact, and it did cause me to think about what we sadly missed. Such a loss underlines the importance of this remarkable performance.

Henry Fogel