This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Cast

- Cover Art

- Full Notes

- First Night

- Critical Review

Drawn from unbroadcast 33rpm acetate disc recordings, this release offers quite reasonable sound quality for a live performance, though some surface noise and a less than totally "hi-fi" frequency range puts it at lower than state-of-the-art for the mid-fifties. That said it's significantly better than the AM radio broadcast that has surfaced elsewhere from the same series of performances.

Our dating of 21 December 1954 is based on detective work centred around the use of stand-in Barbara Howitt for Monica Sinclair in the role of Evadne. Click on the tabs here for extensive additional notes and historic information.

Andrew Rose

Recorded 21 December 1954, Covent Garden, London

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

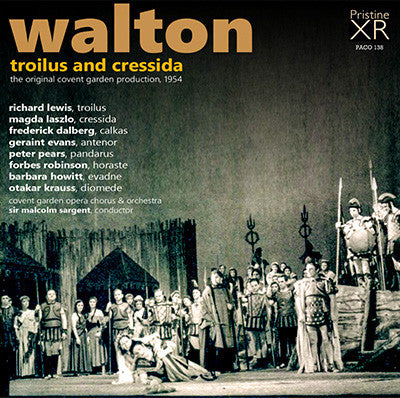

Cover artwork based on a photograph of the death of Troilus (Act 3) from the Covent Garden production

Troilus and Cressida

Opera in three acts

Libretto by Christopher Hassall

Music by William Walton

Scenery by Hugh Casson

Costumes by Malcolm Pride

Producer: George Devine

First performance: 3 December 1954

Covent Garden Opera Orchestra & Chorus

Conductor: Sir Malcolm Sargent

CAST

Calkas, High Priest of Pallas - Frederick Dalberg

Anterior, Captain of Trojan Spears - Geraint Evans

The Voice of the Oracle - Barbara Howitt

Troilus, Prime of Troy - Richard Lewis

Cressida, daughter of Calkas, a widow - Magda Laszlo

Pandoras, brother of Calkas - Peter Pears

Evadne, servant of Cressida - Barbara Howitt

Horaste, a friend of Pandarus - Forbes Robinson

Diomede, Prince of Argos - Otakar Kraus

A Priest - Gordon Farrell

First Soldier - Clifford Starr

Second Soldier - Stanley Cooper

Ladies in attendance on Cressida - Norah Cannell, Jeanne Bowden, Jacqueline Brown, Lilian Simmons

Troilus and Cressida

Walton's Troilus and Cressida, which reflects the composer’s great love of romantic Italian opera, was the closest to his heart of all his works. It had the longest period of gestation - over seven years - but it was to be beset with problems. The première of Britten’s Peter Grimes at Sadler’s Wells in June 1945 had revitalised hopes for British opera. Walton felt keenly the rivalry of fellow composers and John Ireland wrote to a friend: ‘Walton was there, with Lady Wimborne. He must have felt rather a draught, I fancy!’ The spur had come from the BBC, its Director of Music writing informally to Walton on 8 February 1947: 'The BBC has decided to commission an opera and would like you to compose it. I do not at all know how you are placed as regards time, but I very much hope that you will be interested in the idea.' The fee was fixed at £500 - with £175 for the libretto.

Walton’s librettist was the actor, poet, playwright and lyricist Christopher Hassall whose name had possibly been put forward by the BBC. Alice Wimborne, whom Walton ‘loved very dearly’, had been the muse behind his violin concerto. She was ‘very intelligent, very kind and very musical . . . and very good at making me work’. She knew and admired Hassall, best known for his lyrics for the songs of six of Ivor Novello's musical plays, from Glamorous Night (1935) to King's Rhapsody (1949). (Hassall was later to work with Sir Arthur Bliss and Sir Malcolm Arnold. His association with Novello has caused some commentators to be perhaps unfairly critical of his libretto for Walton.)

Alice was closely involved in the early stages of the opera commission, helping in the search for a suitable subject. Her critical perception and understanding of Walton had made her an admirable companion, and on 15 June 1947 she had written to Hassall who, after a number of proposals, had come up with Troilus and Cressida: 'The difficulty is to find the perfect subject. Many that would suit his music have other drawbacks, as a case in point, Byron. For apart from suitability for him the story or plot must be so easy and clear and flowing and scenic. Troilus and C. has got that.'

Throughout 1947 and into 1948 the synopsis was slowly thrashed out. But there were delays when Alice contracted cancer for which treatment was sought in a Swiss clinic. Despite her increasingly serious illness Alice's sympathetic hand was there in support of what she referred to Hassall as 'our child' right up to her death in April 1948. Walton was utterly devastated. An attack of jaundice put him in hospital, after which he recuperated on the island of Capri. Later that year on a trip to Argentina to attend an international conference of the Performing Rights Society, he met his future wife Susana Gil Passo and their whirlwind marriage took place in Buenos Aires in December. They arrived in England in February 1949 and by November they were settled in Ischia, living initially in a building that was too uncomfortable to be any more than a temporary residence before moving to another, a derelict building that they rebuilt and made habitable as their home for eight years. (The land for their final home, La Mortella, was purchased in 1956.) It was against the background of these living conditions that Walton took up again the threads of Troilus and Cressida. Travel, personal tragedy, marriage and the move to Italy had caused a serious disruption to the schedule. As a librettist Hassall was not at first conversant with the style, rhythm and wording of grand opera, but Walton suggested he looked at the libretti of operas like Verdi’s Rigoletto and Un ballo in maschera and study verses of varying lengths and the use of appropriate words. He offered Otello and Aida as models for the timings of the acts, and even suggested that Cressida’s ‘At the haunted end of the day’ in Act II should correspond in length to the aria ‘Celeste Aida’.

Living several months of each year in Ischia did not make working with his librettist at all easy. Much of it was done by correspondence because of the lack of a telephone in his Italian home, and contact by post was slow and laborious. Hassall described their working method:

We naturally worked in close collaboration, either by a stream of letters between London and Italy, or together at Sir William's home in Ischia. . . [He] copied out the initial synopsis so as to examine it the more closely and check on every detail. I then redrafted it and broke it up into numbered sections, and began the actual text on the same pattern, numbers being necessary for easy reference since the work continued by correspondence once the composition of the music began. I kept a pile of envelopes ready stamped and addressed for prompt reply, and our rather extraordinary correspondence over a long period would fill, I should imagine, several volumes. The exact motive or mood at any point was discussed, also the stanza - shape and style of the utterance, for the libretto ranged from measured rhyme to free verse (for instance, the passage in hexameter rhythm in Act 1 was not my idea, but was a 'special request'.) Such requests make a task of this kind all the more stimulating.

There were advantages in this partnership. They got on remarkably well. Changes could be carefully considered over a period of time. Each was sensitive to the other’s ideas, Walton being particularly good at coming up with suggestions for dramatic improvements and Hassall keen to respond. In April 1948 the BBC issued a statement to the effect that it had commissioned Walton to write an opera, and that the libretto had been ‘written by Christopher Hassall in active collaboration with Dr Walton on the theme of Troilus and Cressida, but not using Shakespeare's words or following his play. It is 3 acts.' But this was far from the truth. Ten months later little progress had been made with the libretto, and in February 1949 Stanford Robinson, Opera Director at the BBC, wrote to Walton: 'Warmest congratulations to you on your marriage. . . Will this new happiness have the effect of making you finish your opera quick or slower? . . . So far as I can judge you have not actually got down any Act in anything like a final form.'

On 28 March 1949 Walton wrote to Stanford Robinson: 'The opera position is perhaps a little brighter. At last Christopher & I . . . have really got the libretto into shape so it only now needs the music. The idea at the moment is to get it ready for the 1951 [Festival of Britain] Exhibition.' But by 4 February 1950 it seems that problems with the libretto were still not entirely solved: ‘[It] bristles with difficulties especially libretto ones,’ he wrote to Steuart Wilson, head of the BBC Music Department.

Wilson replied: ‘I would like to know whether you think that we could do - or that you would like to do - it as a public performance in the RAH or South Bank as a first 'concert' performance with or without narrator.’ But Walton, who now seemed to be harbouring some doubts about the work, responded on 1 March: ‘On the whole I'm not keen about a concert performance of Troilus during 1951. For one thing I don't think it would stand the cold hard light of a concert performance, & it may, with luck, just get away with it on the stage. Though for me, it has progressed fairly well, I've been fairly stuck for the last fortnight & I shall be pleased if I get it finished in sketch by this time next year. I aim for a Cov[ent] Gar[rden] performance about June '52.’

The BBC became increasingly impatient at the non-appearance of Troilus. Nevertheless, it recommended 'that the commission remains in force and that the commission fee is paid in respect of the first performance despite the fact that it would be a stage performance'. The Director-General’s feeling that 'We don't want to negotiate with him' was perhaps forgotten when Walton received a knighthood in the Festival of Britain year honours.

The idea for its subject had come to Christopher Hassall after reading a chapter in C. S. Lewis's The Allegory of Love. Analysing the character of Cressida (or Criseide), Lewis had written that from the 'fear of loneliness, of old age, of death, of love, and of hostility . . . springs the only positive passion which can be permanent in such a nature, the pitiable longing, more childlike than womanly, for protection, for some strong and stable thing that will hide her away and take the burden from her shoulder.' Hassall turned to Chaucer's epic poem Troilus and Criseide set amidst the Trojan war, 'with the order of Chaucer's events rearranged, new details introduced, and the whole compressed within much narrower limits of time, until the latter half of Act III where the opera bears no relation to the medieval poem. There is nothing of Shakespeare in the libretto, beyond a similarity of situation here and there inevitable in two works derived from the same source.'

At different stages the libretto was looked at by Ernest Newman, Walter Legge, Ernest Irving and, while staying on Ischia, Wystan Auden to whom Walton played through Troilus. All made valuable comments and criticisms, and it was Auden who solved the problem of ending Act III by suggesting a quintet. This became the sextet which Newman hailed as a successor to the Rosenkavalier trio, the Meistersinger quintet and the Rigoletto quartet. ‘I now understand why no-one has attempted an opera with “love” interest since Puccini. Scyllas and Charybdises surround one at every bar. Give me Buddery every time – or even plain rape,’ he naughtily wrote to Walter Legge in March 1952. (Britten’s Billy Budd had been premièred at Covent Garden the previous December.)

There were interruptions with commissions for the Coronation Te Deum and Orb and Sceptre Coronation March, and in August 1953 Walton sailed to the United States for conducting engagements. But for the remainder of that year and all the following one he was occupied with Troilus which was finished by September 1954. Although dedicated 'To my wife', it must nevertheless have stirred anguished memories of Alice. 'I sweated blood over it - in fact it nearly killed me,' he once remarked in an interview.

Act I opens in the citadel of Troy. Calkas, high priest and father of Cressida, is convinced that further resistance to the besieging Greeks is useless and tries to persuade the people that the Oracle of Delphi has advised surrender. Antenor, a young captain and friend of Troilus, accuses Calkas of being in the pay of the Greeks, but Troilus gives assurance of the priest’s good faith. Unconvinced, Antenor sets off on a foray against the enemy. Troilus meets up with Cressida to whom he declares his love - but to no avail. He is overheard by Pandarus, Calkas’s brother, who promises to plead his cause. Pandarus then hears Calkas bidding farewell to Cressida and discovers that his brother is deserting Troy. He tries to console Cressida with the thought of Troilus’s love but he is interrupted by the announcement of Antenor’s capture. Troilus sends a message to his father King Priam saying that if he fails to regain his friend Antenor by force then an exchange of prisoners must be arranged with the Greeks whatever the cost. Pandarus meanwhile invites Cressida to a supper party at his house the following evening and persuades her to give him the scarf she is wearing which he delivers to Troilus, now convinced of Calkas’s treachery, as a token of her affection.

Act II takes place at Pandarus’s house the next evening; Cressida and the other guests are playing chess. A storm develops and, as part of his plan, Pandarus sends for Troilus and persuades Cressida not to risk going home in such weather but to stay instead. Her servants prepare her for the night and then, alone, she admits to herself that she has fallen in love again. Pandarus then comes with the news that Troilus is in the house because, as he falsely explains, he is racked with jealousy. Overhearing this, Troilus bursts in disclaiming such nonsense. Pandarus slips away and on his return is delighted to see that his plan is working and the two are reconciled.

After a night of passion Troilus and Cressida are disturbed by the sound of an approaching drum. It is Diomede, commander of the Greeks, who has come for an exchange of prisoners. The lovers conceal themselves behind some curtains and Pandarus takes it on himself to conduct the parley. Calkas, it seems, has done the Greeks some good service and will accept no reward other than that his only child be restored to his care, which can be done to meet King Priam’s plea for the return of Antenor whom Troilus failed to snatch back from the Greeks. Diomede produces the seals of Troy and of Greece as proof of the agreement. Searching the room, he sees Cressida and is struck by her beauty. He tells her to prepare for a journey and meet him in the yard. Troilus enters in despair and promises to smuggle messages through the enemy lines, and as a show of his fidelity gives back to Cressida the scarf she gave him the day before.

Act III opens in the Greek encampment ten weeks later, during which time Cressida has received no word from Troilus: her servant Evadne has been destroying all his messages under orders from Calkas who now reproaches Cressida for her coldness towards Diomede. Having heard nothing from Troilus she ultimately yields to Diomede’s advances and allows him to take her scarf as a token of her favour. That very night she is to be proclaimed Queen of Argos. However, during an hour of truce Troilus and Pandarus appear and urge Evadne to fetch Cressida whose ransom is being arranged. Seeing Diomede carrying Cressida's scarf, Troilus claims her as his own. Enraged, he attacks Diomede but is stabbed in the back by Calkas. Diomede orders Calkas to return to Troy but declares that Cressida must stay behind as a prisoner. Seizing Troilus's sword, she takes her own life.

The first performance of Troilus and Cressida, which was broadcast, took place at the Royal Opera House on 3 December 1954. Even once the composition had been completed, the opera seemed plagued with problems. There were initial doubts as to who would be designer and director – ultimately Hugh Casson and George Divine, after such names as Henry Moore, Isobel Lambert and Laurence Olivier had been considered. Then there were casting difficulties, and the greatest disappointment was with the role of Cressida which Walton had written with Walter Legge’s wife Elisabeth Schwarzkopf in mind. After problems in fixing dates she eventually declined with varying excuses that her English was not good enough and ‘the text was Ivor Novello-ish and in English’. How magnificently she would have taken on that role can be surmised from the extracts she recorded in 1955 with Walton conducting [Pristine ****]. Her replacement, the Hungarian soprano Magda Laszlò, could speak little English and had to be coached. Contrary to what one might have expected, the rather camp role of Pandarus, with its occasional Brittenesque phrasing and suggestions of falsetto, was not written with Peter Pears in mind though he proved admirable in the part. Parry Jones was the first suggestion (just as Nicolai Gedda had been for Troilus). Perhaps for Pears’s sake the lines: ‘Come, Troilus, confide in me. I have much experience in these things . . What do you know of love?’ were removed soon after the first performance.

The first orchestral rehearsal nearly had to be abandoned because the parts were littered with so many inaccuracies that had not been properly checked by the publishers. Sargent, who had little experience in the opera pit, clearly did not know the score well enough and for reasons of vanity would not wear glasses, making reading the manuscript score even more difficult. He also refused to beat when the orchestra was not playing, leaving whole ensembles to fend for themselves without setting a tempo. However, whatever problems there were in rehearsal, the first night was counted a success and while the work had a mixed reception in the musical journals the Daily Express critic called it 'the proudest hour of British music since the première of Benjamin Britten's Peter Grimes nine years ago'.

Troilus had seven Covent Garden performances before going to Glasgow, Edinburgh, Leeds, Manchester and Coventry where the conductor was Reginald Goodall (‘worse than hell’ in Walton’s words), and then returning to London for a further five. The American première, which Walton attended, took place in San Francisco on 7 October 1955 with Richard Lewis and Dorothy Kirsten in the title roles and Erich Leinsdorf conducting, and on 12 January 1956 it opened to a reception of boos, cheers and hisses at La Scala, Milan, with David Poleri and Dorothy Dow, Nino Sanzogno conducting.

There were five more Covent Garden performances between December 1955 and February 1956 with Laszlò and Lewis, and Troilus did not return to the repertoire until it was revived, with some alterations and cuts, for five performances in 1963, with Marie Collier a magnificent Cressida, André Turp Troilus and John Lanigan Pandarus. Once again Sargent conducted. (It was on the way to catch a train to see this production of Troilus that Christopher Hassall collapsed and died.) A few years later Walton, much taken by the singing of Janet Baker, tried to breath fresh life into the opera by revising the part of Cressida to accommodate her mezzo voice - transposing down the vocal line as well as reshaping it, and making further changes and cuts elsewhere. Even this production was dogged with problems, especially when at the last minute André Previn, who was to have conducted, had to withdraw because of bursitis. Lawrence Foster stepped in for the six performances and while the singing and playing did much to redeem the opera, the production was let down by sets that spoke only too clearly of tight budgets. Walton nonetheless seemed delighted: 'It was a very special evening for me because I've been waiting for the last twenty years and more to get this opera vindicated. Of course, Janet Baker to me is so beautiful on the stage, and the way she acts and moves is really wonderful, and her singing is divine: there is no other word for it. And it just made me cry.' Sadly more tears were likely reserved for the failure of Troilus to establish itself in the general operatic repertoire. At Covent Garden in 1995 Opera North performed a version that restored the role of Cressida to a soprano voice but nonetheless incorporating many of the cuts made in the ‘Janet Baker’ version.

In between the first performance and the publication of the vocal score, as was Walton's habit, numerous revisions, deletions and changes were made. Most of these were minor details, here and there a bar or two was cut to tighten continuity, a line or two of dialogue omitted, some adjustments made to the scoring. In the first performance early in Act 1 the spoken female voice of the Oracle was heard a second time (she speaks only once in the VS), but that part was cut completely in the final revision. In the performance issued on these CDs that was recorded by the BBC Transcription Service on 21 December 1954 (and not broadcast) there are some substantial sections that have been cut in the final version (and were also cut in the version for Janet Baker) and therefore no longer heard today. The most significant of these are, in Act I Calkas’s long monologue ‘Launching at dead of night’ right up to and including the voice of the Oracle; in Act II the women’s chorus ‘Put off the serpent girdle’ up to Cressida’s ‘How can I sleep?’; Pandarus’s ‘Jealousy, the carrion crow . .’ up to Troilus’s cry of ‘Enough of this damnable lying!’; and several incisions from Act III, Cressida’s ‘He was challeng’d!’ up to ‘ “My Cressida!” ’, Calkas’s rebuking of Cressida: ‘Prince Diomede honours you’ up to ‘The future is what we make it’, and the dialogue between Diomede and Cressida: ‘Would you make a harlot of your captive?’ until Diomede’s ‘I know some Trojans linger in your thoughts’, and soon afterwards Diomede’s six lines beginning ‘Now she is mine . . .’

The inclusion of these cuts, together with the fine singing of Magda Laszlò, Richard Lewis and Peter Pears and (despite his other failings) Sargent’s urgent pacing, makes this recording a document of unusual historic interest.

Stephen Lloyd

author of William Walton: Muse of Fire (Boydell 2001)

From THE TIMES

Sir William Walton’s opera Troilus and Cressida was originally commissioned by the B.B.C. as an opera for broadcasting, but the conception grew in the composer’s mind, which has always worked slowly in each of his symphonic works to make a single decisive utterance in the chosen form, and in the long period of its gestation it has formed itself into a great tragic opera.

The Greeks from Homer to Euripides themselves knew that the bitterness of war is revealed only to women, and from the long line of their heroines, Hecuba, Cassandra, and the Argive queens, they made their tragedies. Cressida, a Trojan woman, caught in the storm of the world and the toil of circumstance, is a tragic figure who moves the spectator with tear for the fragility of human happiness and pity for our lot. Walton has satisfied Aristotle’s canons, not only of pity and fear, but of the dignity and magnitude of the issues, and in so doing he has satisfied one of opera’s demands—the creation of a great soprano role. The text which has provided him with his skeleton is Mr. Christopher Hassall’s reading, not of Shakespeare but of Chaucer, from which he has built up for the composer some firmly drawn characters.

Pandarus is both odious, laughable, and recognizably true to type. He serves the operatic function of comic relief. The opera is laid out conventionally as a music-drama with one or two concerted movements like the sextet In the last act. Walton has been content to write the same sort of music as in his other works: there are the terse figures reiterated in the orchestra to work up propulsive power, the darkly shaded melodies from lower strings, the huge climaxes with an edge on them obtained from the ordinary large orchestra. There is no attempt at innovation, formal or harmonic, no deliberate evasion of the familiar and well-tried devices. The music owes its quality to its saturation. The drama is penetrated and permeated by the music.

The first performance went well. Sir Malcolm Sargent, who has not been at an operatic desk for many years, was vigilant, served the singers with tact, and elicited from the orchestra the astringency which is one of the marks of Walton’s orchestral writing. Mr. Peter Pears got up from a sick bed to sing Pandarus, but one would not have suspected it from the liveliness of his characterization in make-up, gesture, and vocal inflexion. Miss Magda Laszlo, who has greatly improved her enunciation of words since her first Glyndeboume appearances, has the clear, true ringing tones, the physical presence, the natural dignity to command the stage, in short the qualifies which add up to the capacity for tragedy. Mr. Richard Lewis, who had sung opposite to her in other operas, again displayed his vocal and dramatic resource in heroic roles. Mr. Otakar Kraus, who also wins admiration for his versatility, did not really command the voice and demeanour of a Prince of Argos. The smaller parts were adequately realized to fill their place in the well-contrived structure of the opera and the chorus discharged their larger role with massive effect. The performance, then, went well, but there is more in Troilus and Cressida than can be extracted in a first hearing of a first performance.

"Our Music Critic"

Saturday 4 December 1954

WALTON’S OPERA

A PARALLEL WITH WAGNER

BY OUR MUSIC CRITIC

The Times

Friday 10 December, 1954

Walton announced himself to the world

In the early twenties, when the mental climate was flippant and anti-romantic, prepared to experiment and to be amused, with Façade, an essay in experiment and amusement of which the principal characteristics were wit and mockery with bright colours and sharp edges. He was a bright young man of the time. But by 1929 he had revealed—in the viola concerto—that he was at heart a romantic.

He has since revealed that he is also a traditionalist. The hard hitting of Belshazzar’s Feast for a moment seemed to differentiate it front conventional oratorio, but the symphony affirmed his belief in tonality and counterpoint. Still, he is so much a man of the twentieth century that it always comes as a surprise to rediscover the romantic and the traditionalist in him. His romanticism is quite different from that of the nineteenth century and his use of traditional forms and procedures is so forceful that he has clearly, in engineering terms, gone over from steam to electricity. His new opera Troilus and Cressida shows his development as the twentieth-century equivalent of a nineteenth-century composer confirmed and extended, in contrast to most of his contemporaries, who are in reaction from the romantic period. For if one seeks an opera with which to compare Troilus and Cressida the one that comes to mind is Tristan und Isolde.

In both an old, unhappy, far-off tale of love round which the emotions of centuries have gathered is dissolved into continuous music of rich texture. The layout is similar in three acts, of which the first sets the historical scene, the second is an elaboration of a love duet, and the third is catastrophe in a sorrow-charged atmosphere—the scene of Cressida at the stockade of the Argive camp recalls the heavy, fateful mood of the castle in Brittany. Be it noted that to compare is not to equate in an ultimate valuation; nor is it to overlook differences.

Wagner’s music drama is unique in its concentration: in it there is only one theme, one overpowering emotion, and the tragedy is one of a conflict of personal loyalties. In Troilus the tragedy is of another kind and is shot through with the 10 years’ war of Greece and Troy: the character of Pandaros provides comic relief; but if there is not the same concentration, there is a similar intensity. There is a difference, however, between the romantic tragedy of the 1850s and the romantic tragedy of the 1950s: Walton’s second act, with its intermezzo depicting the passion of a tragic night, is not voluptuous: its love is a sell-renewal, an enhancement of life, not a Liebestod. Cressida’s tragedy is not love but war.

A DOUBLE THEME

Mr. Hassall in his skilful libretto, which precipitates dramatic action and holds it up for musical expansion most aptly to a composer’s purpose, actually lays out the drama in Wagners Bogen form, ABCBA: we have Isolde-Tristan, their duet, Tristan-lsolde in Wagner, and Troilus-Cressida, their duet, Cressida-Troilus in Walton. There are complications in the double theme of Walton's opera and in the character of Pandaros, who weaves a counterpoint through the three acts. Walton, moreover, is not a systematic user of leitmotif: even as a symphonist his repetitions and recapitulations are always fluid, never exact. What he has done is to absorb by slow saturation both the superficial romance of the love of man and woman and the deeper tragedy of war's consequences, such as are often depicted by Euripides, and to compose music to these themes straight ahead without thought of precedent or experiment. And so the opera surprises us by the ease with which we apprehend it. We are so used to being puzzled and surprised that when for once the instinct of curiosity is not provoked we are prone to think that there must be something wrong with a rounded work of art that is both romantic and traditional. There is nothing wrong with Troilus and Cressida.