This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

- Synopsis

- Additional Notes

Fabulous 60s Soviet stereo production of Le Coq d'Or

Brilliant sound quality in XR remasters from mint Melodiya discs

As with a number of Soviet-era recordings, the background to this recording is a little murky. When trying to find out why two conductors appear I discovered that it was a recording made for broadcast, but beyond this there is little. Both conductors were experienced, with similar styles, and so one can only offer conjecture as to why they were both involved: time contraints, studio bookings clashing with other commitments, illness, all are possible.

The recording itself is very well made and these transfers, from mint Melodiya LPs, offer very fine quality sound indeed, as well as correction to some rather intrusive pitch problems during the second and third acts.

Andrew Rose

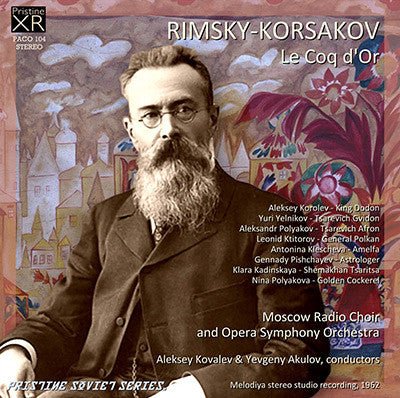

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Le Coq d'Or

CAST

Aleksey Korolev - Tsar Dodon

Yuri Yelnikov - Tsarevich Gvidon

Aleksandr Polyakov - Tsarevich Afron

Leonid Ktitorov - General Polkan

Antonina Klescheva - Amelfa

Gennady Pishchayev - Astrologer

Klara Kadinskaya - Shemakhan Tsaritsa

Nina Polyakova - Golden Cockerel

Moscow Radio Soloists, Choir

and Opera Symphony Orchestra

Aleksey Kovalev & Yevgeny Akulov conductors

Synopsis

Time: Unspecified

Place: In the thrice-tenth kingdom, a far off place (beyond thrice-nine lands) in Russian fairy tales

Note:

There is an actual city of Shemakha (also spelled "Şamaxı", "Schemacha"

and "Shamakhy"), which is the capital of the Shamakhi Rayon of

Azerbaijan. In Pushkin's day it was an important city and capital of

what was to become the Baku Governorate. But the realm of that name,

ruled by its queen, bears little resemblance to today's Shemakha and

region; Pushkin likely seized the name for convenience, to conjure an

exotic monarchy.

Prologue

After quotation by the orchestra of the most

important leitmotifs, a mysterious Astrologer comes before the curtain

and announces to the audience that, although they are going to see and

hear a fictional tale from long ago, his story will have a valid and

true moral.

Act 1

The bumbling King Dodon talks himself into believing

that his country is in danger from a neighbouring state, Shemakha, ruled

by a beautiful queen. He requests advice of the Astrologer, who

supplies a magic Golden Cockerel to safeguard the king's interests. When

the cockerel confirms that the Queen of Shemakha does harbor

territorial ambitions, Dodon decides to pre-emptively strike Shemakha,

sending his army to battle under the command of his two sons.

Act 2

However, his sons are both so inept that they manage

to kill each other on the battlefield. King Dodon then decides to lead

the army himself, but further bloodshed is averted because the Golden

Cockerel ensures that the old king becomes besotted when he actually

sees the beautiful Queen. The Queen herself encourages this situation by

performing a seductive dance – which tempts the King to try and partner

her, but he is clumsy and makes a complete mess of it. The Queen

realises that she can take over Dodon’s country without further fighting

– she engineers a marriage proposal from Dodon, which she coyly

accepts.

Act 3

The Final Scene starts with the wedding procession in

all its splendour. As this reaches its conclusion, the Astrologer

appears and says to Dodon, “You promised me anything I could ask for if

there could be a happy resolution of your troubles ... .” “Yes, yes,”

replies the king, “Just name it and you shall have it.” “Right,” says

the Astrologer, “I want the Queen of Shemakha!” At this, the King flares

up in fury, and strikes down the Astrologer with a blow from his mace.

The Golden Cockerel, loyal to his Astrologer master, then swoops across

and pecks through the King’s jugular. The sky darkens. When light

returns, queen and cockerel are gone.

Epilogue

The

Astrologer comes again before the curtain and announces the end of his

story, reminding the public that what they just saw was “merely

illusion,” that only he and the queen were mortals and real.

Preface to The Golden Cockerel by librettist V. Belsky (1907)

The purely human character of Pushkin's story, The Golden Cockerel – a tragi-comedy showing the fatal results of human passion and weakness – allows us to place the plot in any surroundings and in any period. On these points the author does not commit himself, but indicates vaguely in the manner of fairy-tales: "In a certain far-off kingdom", "in a country set on the borders of the world".... Nevertheless, the name Dodon and certain details and expressions used in the story prove the poet's desire to give his work the air of a popular Russian tale (like Tsar Saltan), and similar to those fables expounding the deeds of Prince Bova, of Jerouslan Lazarevitch or Erhsa Stchetinnik, fantastical pictures of national habit and costumes. Therefore, in spite of Oriental traces, and the Italian names Duodo, Guidone, the tale is intended to depict, historically, the simple manners and daily life of the Russian people, painted in primitive colours with all the freedom and extravagance beloved of artists.

In producing the opera the greatest attention must be paid to every scenic detail, so as not to spoil the special character of the work. The following remark is equally important. In spite of its apparent simplicity, the purpose of The Golden Cockerel is undoubtedly symbolic.

This is not to be gathered so much from the famous couplet: "Tho' a fable, I admit, moral can be drawn to fit!" which emphasises the general message of the story, as from the way in which Pushkin has shrouded in mystery the relationship between his two fantastical characters: The Astrologer and the Queen.

Did they hatch a plot against Dodon? Did they meet by accident, both intent on the king's downfall? The author does not tell us, and yet this is a question to be solved in order to determine the interpretation of the work. The principal charm of the story lies in so much being left to the imagination, but, in order to render the plot somewhat clearer, a few words as to the action on the stage may not come amiss.

Many centuries ago, a wizard, still alive today sought, by his magic cunning to overcome the daughter of the Aerial Powers. Failing in his project, he tried to win her through the person of King Dodon. He is unsuccessful and to console himself, he presents to the audience, in his magic lantern the story of heartless royal ingratitude.

Fanfare Review

I can’t see this recording be surpassed anytime soon

Vasily Vasilyevich Yastrebtsev, friend and student of Rimsky-Korsakov, noted in his diary that upon the completion of The Tale of the Tsar Saltan, its composer stated he was finished with fairy-tale operas. It was a singularly poor prediction, at least in one sense. Rimsky-Korsakov would turn to Russian fairytales as a medium for exploring other themes: selfishness and love in Kashchei the Deathless; love, sullied by humanity, only pure on the other side of the grave in The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh; and a viciously funny satire of unitary power in specific and humanity in general, in The Golden Cockerel.

Begun in 1906 and finished the following year, Rimsky-Korsakov never intended the work as a reflection on the current regime. There’s no resemblance between the elderly, lustful, self-indulgent, self-pitying widower King Dodon in The Golden Cockerel, and the middle-aged, shallow, gentle, but easily swayed Nicholas II. But the times were politically volatile, and any criticism of rulers, however oblique, was bound to come up against the iron wall of censorship in late Tsarist Russia. The composer never lived to see its premiere, which took place in 1909. A shame, as it was to prove in some respects his operatic masterpiece, a work of harmonic audacity, orchestral brilliance, and transformational subtlety.

Curiously, the Soviets waited until 1962 to record The Golden Cockerel. Even more curiously, there are two conductors involved, and two Queens of Shemakhan. The conductors are Alexei Kovalev and Yevgeni Akulov. And while the complete recording lists Klara Kadinskaya as the Queen, another act II was also released separately at that time on a single disc, featuring Galina Oleinichenko—again with Kovalev and Akulov. This would seem to point to the possibility that The Golden Cockerel, like a very few other Soviet opera recordings, was made with a double set of leads, so the masters could be easily slotted into the finished product and create two different complete versions of the opera. But there’s no evidence this practice was still in use by 1962. Another possible scenario is that Oleinichenko had originally been contracted for the complete recording—Korolev can be heard in her version, too—but that the recording was halted and that Oleinichenko, for whatever reason, could not return to the studio to finish it. But why would the two conductors still be listed for Oleinichenko? Perhaps Melodiya’s records were confused, or not even consulted, when transfers were later made. Or maybe one of the two was available, like Oleinichenko, for only a short period of time.

The result, regardless, is worthy. Soviet-era opera recordings tended to be compromised through political choices and seniority, but the cast here is uniformly excellent. Alexei Korolev, then just past his prime, huffs and fudges his intonation occasionally, and pushes for greater chest resonance—but that only makes this extraordinarily expressive artist all the better suited to the buffo Dodon, and certainly more so than his contemporary attempt as the evil Prince Mstivoi in Mlada. Kadinskaya has the stratospheric reach but also the agility and tonal allure for the Queen (Oleinichenko’s tone is much slimmer), and Gennadi Pishchayev’s eerily sexless high tenor is perfect for the Astrologer. Even the smaller parts boast riches: sweet-toned Yuri Yelnikov makes a stirringly enthusiastic Guidon, and Alexander Polyakov a smooth-as-silk Afron, with a touch of the quick vibrato that can be heard in Pavel Lisitsian’s work. Nina Polyakova is as hair-raising in the title role as she would be after a different fashion the following year as Fata Morgana in Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges. A shame this fine singer’s tight focus, upper range, and endless reserves of breath relegated her on records largely to secondary parts, but one can’t question the results. Kovalev and Akulov, however they divided up the work, carefully reveal all the opera’s subtleties without in any way losing momentum.

Andrew Rose, whom I praised for his restoration on Tchaikovsky’s The Oprichnik (Pristine Audio 101) rightly praised the quality of sound on this original release. He corrected some pitch issues in the last two acts, but otherwise let well enough alone. The clarity is better than on my various LP copies, but they suffer from analog side noise to varying degrees. Note, too, that the suite from The Invisible City of Kitezh, included in the original set, was too long to include here, but is available as a free download from Pristine.

I can’t see this recording be surpassed anytime soon. The Golden Cockerel is a very difficult opera to bring off live, and there doesn’t seem to be much interest in creating a new studio version either. That’s unfortunate, but the sound on this issue has aged well. Highly recommended.

Barry Brenesal

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:5 (May/June 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.