This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

Toscanini's Traviata - The electrifying 1946 NBC broadcasts

Even livelier in this new 32-bit XR Pristine remastering for Verdi's 200th birthday

Toscanini's broadcast recordings of La Traviata spanned two live transmissions a week apart in December 1946, and that is how we've split them here: first Act 1 and Act 2, Scene 1, then Act 2, Scene 2 and Act 3.The pace is certainly brisk - some twenty minutes quicker than Callas under Santini in 1953 - yet Toscanini's brilliantly-drilled musicians bring it off with aplomb.

As with most of Toscanini's NBC broadcasts of this era, the original sound has been well-preserved. It's no great surprise to find Gramophone's reviewer baulking at the Studio 8-H acoustics; as a part of this remastering, which has greatly improved the overall sound quality, I've also made judicious use of the reverberant profile of one of the world's great opera houses, a technique which greatly aids the projection and enhances the enjoyment of the singers here who, as a result, probably deserve something of a reappraisal.

Andrew Rose

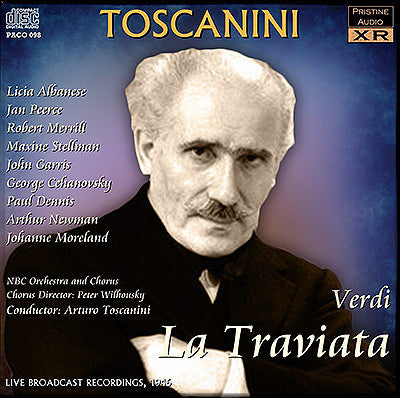

VERDI La Traviata

Broadcast performances

CD1: 1 December, 1946

CD2: 8 December, 1946

NBC Studio 8-H

New York City

First issued as RCA LM-6003

Violetta Valery - Licia Albanese

Alfredo Germont - Jan Peerce

Giorgio Germont - Robert Merrill

Flora Bervoix - Maxine Stellman

Gastone - John Garris

Baron Douphol - George Cehanovsky

Marquis d'Obigny - Paul Dennis

Dr. Grenvil - Arthur Newman

Annina - Johanne Moreland

NBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus

Chorus Director - Peter Wilhousky

Conductor - Arturo Toscanini

Fanfare Review

The Pristine remastering is a significant improvement over any earlier incarnation I have heard

As with other Pristine “XR Ambient Stereo” remasterings, I list the recording as monaural in the headnote because what Andrew Rose does at Pristine does not turn it into a stereophonic recording, but rather creates (very effectively) a kind of stereophonic ambience around the original recorded sound. For those readers who already know the RCA edition this recording (this is the actual broadcast, spread over two dates a week apart; it is not the dress rehearsal which was released by Music & Arts), you know how you view it and will be most curious about the sound quality. The Pristine remastering is a significant improvement over any earlier incarnation I have heard of this performance, on RCA LPs and CDs. Rose has gotten a warmth out of the sound, and has created a perspective that offsets some of the horrible closeness and dryness of the 8H sound so beloved by Toscanini and few others. In Rose’s own notes, he says “I’ve also made judicious use of the reverberant profile of one of the world’s great opera houses, a technique which greatly aids the projection and enhances the enjoyment of the singers here who, as a result, probably deserve something of a reappraisal.” One might think that a bit of self-serving puffing of the wares, but in fact it is a fair statement of his accomplishment. Anyone who loves this performance will want this edition of it.

When this arrived from Fanfare headquarters I almost sent it back, since I am rarely sympathetic to Toscanini’s conducting despite many years of really trying. (I know it is not a prejudice, because if I turn on the radio in the midst of a Toscanini performance without hearing the announcement identifying it, I generally don’t react well to it and only find out later who the conductor is). There are exceptions, of course. And I recognize that so many great and important musicians and critics do react positively to Toscanini, and therefore the problem is mine. Although I do own this performance I have not heard it in years, and so I decided to take on the review and give it a reappraisal.

For the most part, my reaction remains unchanged, though perhaps I gained a somewhat greater understanding of those feelings. For me, music is first and foremost about sound—more than it is about any of the formal elements (harmony, melody, rhythm) that make it up. Clearly all are important, and harmony is in particular a crucial component of sound, but the quality of orchestral, instrumental, or vocal sound is a key determinant of my identification with a performance. It is precisely in this area where Toscanini falls most seriously short. The famed dry acoustic of Studio 8H, which we now know that he liked and even tried to replicate on broadcasts and recordings made at Carnegie Hall, is simply not a pleasant listening experience. But Toscanini’s sonic ideal was the sound that he heard on the podium directly in front of the orchestra. Almost every other conductor in history has understood the important difference between on-the-podium sound and that heard by the audience out in the house. Conductors will frequently go out into the house for a few moments of rehearsal to listen to the sound, and they also learn what a hall is like by hearing other conductors’ concerts. I spent a great deal of my professional life working with great conductors and talking with them, and I never heard one express that the sound they were seeking to create either in a concert hall or a recording would duplicate what they heard on the podium. So it is impossible for me to blame RCA for this problem with 8H recordings: Toscanini had as much power as any conductor alive at the time, and he got the sound he wanted. It is not a sound I find appealing. It is not just recorded sound to which I am referring, though that is symbolic of the problem. I prefer orchestral sound built from the bottom up, constructed on a foundation of basses and cellos. Toscanini’s sonority seems to me more top-down.

Beyond quality of sound there is the driven, intense quality to much of Toscanini’s music-making. It is not just a matter of fast tempos; in fact, tempo is a minuscule component of the quality. Some of it is rigidity of phrasing, much of it is the nature of orchestral attacks. It is apparent early on, in the opening Prelude, when the big tune comes. The strings bite into the first note of that tune, and over-articulate the entire melody. It is important to note that there are many quite extraordinary qualities Toscanini brings to the score. The precision and commitment of the orchestral playing, the unmistakable sense of momentum, the excitement of the big scenes, the fact that there is not one measure that seems “phoned in,” these are all admirable qualities that are not always found in standard opera performances. There is a sense of occasion about this whole performance that one feels from beginning to end. But there is also, at least for me, the lack of some important elements of the score: charm, elegance, beauty, and tenderness are a significant part of the makeup of La traviata, and they seem undervalued here.

It takes Albanese a bit to warm up, or perhaps to relax into the role, but when she does she gives a more complete portrayal than many. She manages the coloratura for “Sempre libera” better than one might have expected, but fully comes into her own in the second act. She may lack the vocal richness of Ponselle, or the range of color and inflection of Callas, but she brings Violetta to life more convincingly than most. Her reading of the letter is particularly touching, as is her singing of “Addio del passato.” Peerce is in good voice here, but there is very little variety of tone or dynamic shading in his performance; it lies mostly between mezzo-forte and forte, and there is a bumpy approach to what should be legato singing. It must be admitted that there was a shortage of quality lyric tenors in the Italian repertoire in the mid-1940s, but wouldn’t it have been wonderful if Toscanini and NBC had gotten Bjoerling for this recording? Merrill may possess the most luscious, juicy baritone voice ever to record the role of Giorgio Germont, and he sings with a natural and innate musicality. In the end, this role needs characterization of the kind that Gobbi gives it on the EMI recording (or even Zanasi on Callas’s Covent Garden recorded performance). The contrast between Albanese’s complete involvement in the character and Merrill’s gorgeous vocalism in the big scene between Violetta and Germont is not a comparison that favors Merrill.

The remainder of the cast is good, and as indicated earlier the orchestra plays brilliantly. As usual, minimal notes and no libretto are provided. This performance has been reviewed twice previously in Fanfare: Marc Mandel was even more negative in 15:4 than I am here, though we basically hear the same faults, but Jon Tuska, in 16:1, entered it into the Classical Hall of Fame.

The most interesting comparison for me was with the Music & Arts release not of this broadcast performance, but of the dress rehearsal and other rehearsal material edited down to a complete performance (CD-4271). It is true that this rehearsal compilation is in many ways more relaxed than the broadcast; Merrill in particular seems more dramatically convincing here, and the conducting is a bit more relaxed (notably in the first act Prelude). But it remains a curiosity for most listeners, interspersed as it is with shouts of instruction or encouragement from the conductor. They are too frequent and too loud for this to pass as a legitimate recording of the opera. The sound lacks the warmth and space that Pristine has given the broadcast, but it is a bit less fierce than RCA’s sound for the broadcast.

Henry Fogel

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:4 (Mar/Apr 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.