This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

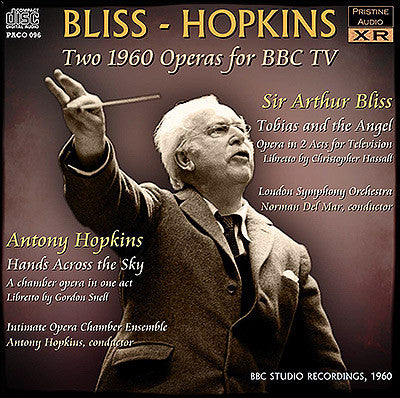

- Cover Art

- Tobias & The Angel

- Hands Across The Sky

BLISS Tobias and the Angel - HOPKINS Hands Across the Sky

Two incredibly rare British operas from BBC TV productions in 1960

These two remarkable productions originate from the archives of Lewis Foreman, who has generously provided both the recordings and his own notes, as well has offering invaluable help with tracking and annotating the works.

Of the two, the Bliss is the less-well preserved, though for live TV sound of this era it's still remarkably good. A lot of work has gone into getting as clean, full and clear a sound as possible here, and despite a lack of very high treble and some peak top-end distortion (largely tamed), it has come out very well. This is the only known recording and performance of this work.

Antony Hopkins' Hands Across the Sky came from a BBC Transcription disc which delivered much better sound quality - clean, crisp and with an excellent frequency range. Although one title from the opera has appeared on recent compilations of the composer's music, we can find no other recording of the complete work. It seems doubtful that any video images remain of either TV broadcast.

Andrew Rose

Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975): Tobias and the Angel

Opera in Two Acts for Television (1960)

Libretto: Christopher Hassall after the Apocryphal Book of Tobit

- Prelude

- Act I Scene I: Nineveh. The market square.

- Scene II: A door in a back street

- Scene III: the river bank

- Scene IV: The embattled City of Ecbatane.

- Rachel’s garden

- Prelude

- Act II Scene I: Sara’s bedchamber and adjoining terrace. Evening

- Scene II: The same. Next morning.

- Scene III: Nineveh. The market square.

First performance:

- Trevor Anthony (Bozru)

- Carolyn Maia (Rhezia)

- John Ford (Tobias)

- Ronald Lewis (Azarias)

- Jess Walters (Tobit)

- Janet Howe (Anna)

- Richard Golding (Raguel)

- Elaine Malbin (Sara),

- Roy Patrick (Asmoday)

- William Lyon-Brown (Beggar)

- Electronic sounds by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

- Special effects: Jack Kine and Bernard Wilkie.

Producer: Rudolf Cartier. Associate conductor and chorus master Brian Priestman.

London Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Norman Del Mar

Live recording, BBC Television, 19 May 1960.

Notes

Sir Arthur Bliss’s opera Tobias and the Angel was commissioned by BBC Television and it was first seen in a live telecast on 19 May 1960, its only production, the performance reissued here. The libretto is by Christopher Hassall − after the Apocryphal Book of Tobit − who sets the story in two acts. The score is dedicated to Trudy Bliss bythe composer and the author.

Bliss was probably best known for his pioneering ballet scores Checkmate, Miracle inthe Gorbals and Adam Zero, and his film music for Things to Come. His varied catalogue of orchestral works spans more than fifty years from A Colour Symphony of 1921-2, to the Metamorphic Variations of 1972, as well as concertos for piano and violin. His choral music is crowned by his First World War memorial to lost comrades, Morning Heroes, and his chamber music includes memorable oboe and clarinet quintets and two string quartets. As Master of the Queen’s Music after 1954 his occasional works and fanfares for royal occasions are iconic. His three-act opera The Olympians, seen at Covent Garden in 1949, and his version of The Beggar’s Opera, produced for a film released in 1953, are all that precede this television opera for the operatic stage.

Bliss takes the story from the Apocrypha – the Book of Tobit. In the 8th century BC the people of Israel are in exile among the Assyrians, and the story opens and closes in the city of Ninevah. We first hear a market scene where Bozru is selling slaves and hiring workers. Tobias seeks to hire a guide to the city of Ecbatane in Media. His choice, is unknown to Bozru, has no baggage and asks an impossibly small payment. Against his mother, Anna’s feelings Tobias’s blind father − Tobit − is sending Tobias on a journey to reclaim a loan in order to relieve their threatening destitution. The hired man, Azarias, is to be his guide. On the journey, by a river Tobias is seized by a great fish which drags him down. Azarias tells him how to catch it and when landed insists Tobias remove the gall and liver and place them in his bundle.

Over an animated orchestral link the scene changes to Raguel’s garden in the embattled City of Ecbatane. Enter Sara, the beautiful daughter of the house, surrounded by her attendant women. Among them is Rhezia whom we first encountered being sold in the slave market at the outset. We gather that Sara is in a rage and is haunted by the memory of seven dead husbands, killed in their marriage beds. We soon learn that she is possessed by the baleful spirit Asmoday.

Tobias now encounters Sara and is instantly smitten by her. Her father, Raguel, enters and is hostile until he realizes Tobias’s identity. He is the very person Tobias is looking for and the traveler is warmly received. Tobias’s declarations of love for Sara are resisted by her father who knows the fate of his daughter’s previous spouses. Tobias insists he will stay but prays for salvation. Azarias (whom we soon learn is in fact the Archangel Raphael) raises his arms as if to protect him. The first Act ends as, terror-stricken, Tobias falls prostrate.

The Prelude to Act two leads us to Sara’s bedchamber where she is being dressed for her wedding ceremony by her young women. As one of them takes the veil from a cupboard the shadow of what might be a claw and forearm momentarily passes over the open cupboard. The women sing a wedding song, and an uproarious drinking song follows sung by members of the household (male chorus). Azarias rallies his master’s courage, and instructs Tobias to chop up the fish’s liver from his bundle, crumble it to powder and burn it in the incense burner by the open shutters of the bedchamber. Raguel makes one last attempt to discourage Tobias but as he leaves the lovers launch into a love duet (‘Like streams we are met, my dear one’).

Sarah’s mood changes and she attempts to belittle and dismiss Azarias, Sara’s voice suddenly becoming the spoken voice of Asmoday. Tobias frantically places the powder on the flaming burner and smoke billows round the room. Azarias summons Asmoday and commands him to stand away from the house. Asmoday appears and Azarias reveals himself as Raphael ‘manifest in the golden panoply of the heavenly host’. They battle over an orchestral interlude (done in stylized silhouette on the black and white television screen) until the Archangel’s Victory is majestically sounded by the orchestra and we move to Scene II with an orchestral introduction. It is the next morning ‘One can hear the birds waking. There is benediction in the air. Sara lies on her bed where she fell. Tobias is sitting with his back against the door. Azarias, the ordinary manservant again, is seen asleep on the terrace below the open shutters of Sara’s window.’ They wake amazed to find all is well, and as Rhezia, then Raguel and finally Azarias join the ensemble, as they sing a hymn of thanks.

Azarias urges Tobias to return to his father and they depart for Nineveh. An orchestral prelude to Scene 3 returns us to the market at Nineveh where Bozru is in full flow selling slaves. Among them are Tobias’s parents. In an episode of grotesque comedy Tobias bids for them and then rubs the fish’s gall in his blind father’s eyes. Tobit’s sight returns and he stares into the face of the Archangel Raphael – revealed alone to him – and as the opera ends Bliss writes in the score: ‘they are seen bowed with their heads to the earth, in a semi-circle of adoration around a slowly forming column of light’.

NOTES BY LEWIS FOREMAN

A chamber opera in one act (1959)

Libretto: Gordon Snell

- Eric Shilling (Professor Neutron)

- Ann Dowdall (Miss Fothergill, his Assistant)

- Stephen Manton (Squeg, a Thing)

- Richard Baker (?) Narrator & announcer

Intimate Opera Chamber Ensemble

conducted by Antony Hopkins

- Scene: Professor Neutron’s Laboratory

Time: The near future.

BBC studio recording, ca 1960

Notes

Antony Hopkins was long known to a wide audience for his BBC Radio series ‘Talking About Music’ in which, notable for the ease and informality of his delivery, each week he analyzed a major work from the repertoire, illustrated at the piano. The series ran for nearly forty years – over a thousand scripts – and survives as a series of published guides to the repertoire.

In his autobiography, Beating Time, Hopkins lists music composed by him from 1943 revealing that he won a Cobbett Prize for a String Quartet in that year. He quickly established a career writing incidental music for the theatre, for BBC radio productions, films, ballet and occasional works for a variety of instruments including three Piano Sonatas, instrumental music and choral music. His one act operas are largely opera buffa in intention and he also produced two operas for young people – Rich man, Poor Man, Beggarman, Saint and Dr Musikus. He was awarded the CBE in 1976.

He enjoyed a long association with the Intimate Opera Company presenting a variety of chamber operas, many of them newly composed. His operas include Lady Rohesia (1948), Three's Company (1954), and the work recorded here. To celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Company in 1959 a competition was held for the best libretto for an opera suitable for the Company’s limited means. The prize went to Gordon Snell for his Hands Across the Sky. Hopkins tells us that several composers were approached to set this libretto, but ‘finally I agreed to do it myself, although I deprecate too much “in-breeding” in an opera company, and would have preferred to bring in some new blood. In the event, I have seldom enjoyed composing anything so much as this gay and witty libretto with its opportunities for comedy, drama, and pathos.’

There are three characters in this comedy: Professor Neutron, Miss Fothergill, his Assistant; and Squeg, a Thing. In his laboratory Professor Neutron and his middle-aged assistant, Miss Fothergill, are engaged in a hazardous search for a new rocket fuel. The experiment fails – again – and to encourage him Miss Fothergill sings a waltz-song of encouragement: ‘Science, science is my passion’. As it becomes a duet the professor reveals his hidden devotion: ‘ I much prefer the sight of her to further exploration’.

They see an approaching object from space which delivers an unusual visitor to the laboratory – with green skin, horns and long hair. It is Squeg, a Thing. Squeg is shy and sings: ‘I’ve searched the Solar System from end to end, no friendly welcome . . . no wish to offend’. This becomes a duet with Miss Fothergill, and as the professor offers a cup of tea the duet becomes a trio. When the Thing announces ‘my name is Squeg’, the professor responds ‘One of the Saturn Squegs I assume!’ Miss Fothergill has fallen for Squeg and launches into her love song in swing style – as she boogies she declares ‘I love Squeg’. She grapples with the reluctant Squeg, singing ‘Squeg, dear Squeg, we’ll fly away together’. The professor returns and thinks the Thing has gone insane and announces he will shoot him. A trio ensues as she sings ‘Because I love him till I die’. Miss Fothergill leaves, dragging Squeg with her, and the Professor sings disconsolately of what might have been: ‘Side by side, teacher and guide’. He determines to dispose of his rival, and sets out to concoct a potion.

Meantime, Miss Fothergill continues to pursue Squeg and she, too, determines to invent a potion to make her a ‘monster just like Squeg’. The unhappy professor sings: ‘This way to the tomb’ and then sings of his adoration for Miss Fothergill but she rejects him. He decides to die, and drinks the potion he prepared for Squeg. However, he picks up the wrong glass, and drinks Miss Fothergill’s potion instead. His appearance changes to that of Squeg. She sings of her love and all three join in a closing trio ‘Glorious life’.

Antony Hopkins wrote about the score: ‘The music is almost entirely

based on four very brief 'motifs'. The most important is the two

conflicting intervals of a fourth, one rising and one falling, with

which the work begins. This might be called the Squeg motif no. 1,

representing the fear a creature from outer space might well inspire in

humans. Squeg motif no. 2 is a note repeated four times and rising a

tone on the next beat (Ta-ta-ta-ta TUM). This represents Squeg as he

really is − timid and insecure, and it is frequently used as an

accompaniment. Also important is a three note phrase, mi-fa-mi in sol-fa

notation, which is used to represent love, either forlorn or

triumphant. For example, the soprano has a sad little lament when Squeg

has left her; it is based on these three notes, treated as a canon

between voice and orchestra. The same pattern reappears in a different

harmonisation in the finale. The equivalent lament for the baritone,

"side by side, her teacher and guide," is worth mentioning; it is a

ground bass, in which dark thoughts concerning Squeg are represented by

the ‘fourths’ motif in the bass, and the idea of partnership − “side by

side, hand in hand” − suggested by a canon. This number appears later as

a duet when soprano and baritone alike bewail their loneliness. For all

its nonsense, this score is very tautly constructed; however, in a 45

minute opera, the scale of ensembles and arias must be

somewhat reduced to preserve the right proportions.’

Hands Across the Sky was first produced at the Cheltenham Festival on 8 July 1959 and on BBC television on 7 February 1960.

NOTES BY LEWIS FOREMAN

MusicWeb International Review

Tobias and the Angel is a very fine opera. The BBC did a wonderful job with this in 1960

The history of British opera is so full of injustices, inertia,

discouragements, false starts and aborted projects and careers that

singling out a particular case for re-evaluation will always be

contentious. There is an obvious danger that as different groups lobby

for different composers and different operas the collective case for

British opera actually weakens, and British opera companies can excuse

themselves from righting wrongs by politely observing that they can’t

please everyone, though they welcome suggestions. Meanwhile, the release

of recordings like the one under review does at least allow a

reasonably happy compromise between staged revival and complete

oblivion. A realistic prediction is that anyone who loves the music of

Arthur Bliss will have to have it, anyone with a serious interest in

twentieth-century British opera might (and should) add it to

their collection, and everyone else will simply ignore it. But let me be

wildly optimistic for a moment and suggest that maybe, just maybe, it

could bring Bliss the opera composer a little of the justice he has long

been denied. Perhaps, in the next few years, there could be one less

production of a Benjamin Britten opera, and one more of another British

‘B’.

Bliss’s entire operatic ‘career’ - though that is

hardly the right word - was lived in the gigantic shadow cast by

Britten, and has never emerged from it. His first and most ambitious

opera, The Olympians, was produced at Covent Garden in 1949. It

is by no means a perfect opera, if such a thing exists, though its

weaknesses can be largely blamed on J. B. Priestley, Bliss’s

distinguished librettist, whose rejection of anything like Brittenesque

realism produced some rather two-dimensional characters. Musically it is

stirring, magnificent, and the story really grips the imagination. The

initial production was massively under-rehearsed, but still impressed

many reviewers, including that hard-to-please Wagnerian Ernest Newman.

John Allison recently told me that he knows people alive today who

attended the premiere, and that they still go misty eyed when speaking

of it. In some countries an opera which had achieved this much would

soon have merited a revival. Not in Britain. It was not performed again

until 1972, when a single concert performance of a shortened version of

the score was put on to mark Bliss’s eightieth birthday (a recording of

this has been released on CD). The fact that The Olympians was so

quickly placed on the institutional shelf seems to have killed off

Bliss and Priestley’s original plan to work on further operas together -

what a loss.

Towards the end of the 1950s, fortunately,

Bliss was tempted by a BBC commission to write a second opera. This time

his librettist was Christopher Hassall, who had honed his skills in his

collaborations with Ivor Novello. The resulting work, Tobias and the Angel,

was given a single BBC television broadcast on 19 May 1960. The

economics of television opera have always been baffling, but the BBC

spent a lot of money on Tobias, and it received good reviews, so

the corporation’s decision not to broadcast it again stands out as

extraordinary even in this admittedly surreal world. Bliss did not

intend Tobias to be simply a television opera, and he prepared a

slightly adapted version of the score suitable for conventional

theatrical performance. Amazingly, the opera still awaits its theatrical

premiere, and after this second demonstration of his country people’s

apathy Bliss unsurprisingly wrote no more operas. The sound recording of

the 1960 broadcast that is now available gives a good idea of what has

been lost, both actually and potentially.

Tobias and the Angel is a very fine opera. Bliss was faulted for over-egging the pudding a bit in The Olympians, and Tobias

can be recognised as an intelligent artist’s response to such

criticism, though the TV medium, too, probably played its part in

encouraging him to adopt a leaner, more economical approach. Tobias

is instantly recognisable as by the same composer, however, and the

dramatic material is in fact quite similar, with the Archangel Raphael

having assumed human form as the ‘hired man’ Azarias in the same way

that the ancient Greek deities had been transformed into strolling

actors in the earlier opera. The dramatic shaping of the material is

finer in Tobias, and the excitement mounts steadily through a

series of succinct and nicely contrasted and nuanced scenes until the

climactic encounter between Raphael and the demon Asmoday is reached. I

use the word ‘excitement’ in its normal sense, incidentally, not as it

is sometimes used in arts criticism, to signify something like aesthetic

arousal. The climactic scene of Tobias and the Angel is

genuinely chilling, and it was a masterful stroke of Bliss’s to make

Asmoday a spoken role, with the voice, according to the libretto, ‘not seem[ing] to come from the SHAPE itself but to be in the air around us, or even not external at all, like a thought in our own minds.’ The BBC did a wonderful job with this in 1960. A similar effect has since been contrived for Lloyd Webber’s Phantom of the Opera.

The present recording is of course of a television broadcast, and with

no libretto supplied, following the action is not always easy -

especially as Bliss, who had been writing for the cinema long before he

turned to opera, often relies on the orchestra to carry the story. At

such moments it is frequently easy to guess what has happened so

descriptive is the music: for example when a quarrel between Tobias and

Azarias is averted by the latter ‘bow[ing] his apology’. At other

times, though, it is impossible to tell from the music alone what was

being represented on the television screen, for Bliss was choosing to be

more broadly atmospheric. Nevertheless, the energy and conviction of

the music carry the listener through the obscurer parts, and it is the

treatment of the orchestra which most clearly reveals Bliss’s

distinctive, film-influenced, concept of opera and fine feeling for

dramatic effects.

The companion work, or filler, is Antony Hopkins’ Hands Across the Sky,

less than half the length of Bliss’s opera. It was apparently chosen

because, though written for stage performance by the Intimate Opera

Company (who gave the premiere in 1959), it was broadcast by the BBC

just three months before Tobias and the Angel, on 7 February

1960. This does not seem a particularly strong reason for placing it

beside the Bliss work, and moving from one opera to the other is a

little disconcerting, for they are totally different in character.

Hopkins’ work, with a libretto by Gordon Snell, was described as ‘an

opera of the near future’, and concerns the arrival on earth of the

alien Squeg (a strange green creature), and the romantic havoc he causes

when he inspires passion in the matronly bosom of Miss Fothergill.

Opinions will differ as to whether it is more fun than silly or more

silly than fun, but there can be no doubt that it is very dated, in the

same way that the flying saucer scene in Salad Days is dated.

Probably not thinking much of posterity, Hopkins clearly delighted in

his subject, for which he composed tongue-in-cheek music with a

delightful Mozartean sparkle. Hands Across the Sky is much easier to follow than Tobias and the Angel,

partly because it actually includes a spoken narration of the kind

often used in radio broadcasts, and partly because it all takes place in

one room, in standard Intimate Opera style. Nevertheless, like many

purely farcical works itreally has to be seen to hold the

attention. If such material as this survives, I would personally rather

have heard one of Hopkins’ earlier, non-sci-fi operas for Intimate

Opera, written in collaboration with Michael Flanders, for they were

televised too. Perhaps they will make up some future release.

I was one of the fortunate few (apparently) who already had a recording of the 1960 Tobias and the Angel.

Comparing the Pristine Audio release with that, I am very impressed

with how much the sound quality has been improved through Andrew Rose’s

careful remastering. The music has far more brightness and clarity - one

must suppose that it sounds greatly superior to what it would have done

through a 1960 television set! The only disappointment is the soprano

part, which now sounds screechy where before it sounded slightly

muffled: I assume that this has something to do with what Rose

apologetically calls ‘peak top-end distortion’ in his ‘Producer’s Note’.

The sound quality of Hands Across the Sky is superb, as are the performances, and this must stand as a definitive record of the work by those for whom it was composed.

I shall enter a small grumble at the packaging offered with the CD. It

contains a single folded sheet printed on one side, and the information

that ‘Full programme notes can be found online’. In fact the useful

notes by Lewis Foreman online are not particularly full, and could for

the most part have been accommodated on the reverse side of the CD

insert. It is hard to believe much in the way of costs was saved by not

printing them, and in printed form they would have been insured against

any closure of the website. And a correction: Andrew Rose’s ‘Note’

(which is printed on the CD insert) states that ‘It seems doubtful that

any video images remain of either TV broadcast.’ Yet Jennifer Barnes’

book Television Opera (2003) states categorically that there is a video recording of Tobias and the Angel in the National Film and Television Archive. And Helga Bertz-Dostal’s classic but scarce Oper in Fernsehen

of 1970 reproduces three photographs of the production. Assuming Barnes

is right, there is a slim but mouth-watering possibility that the 1960 Tobias and the Angel

will one day be available for purchase in a video medium. In the

meantime, can some opera company please just go ahead and stage it?

David Chandler

MusicWeb International