This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

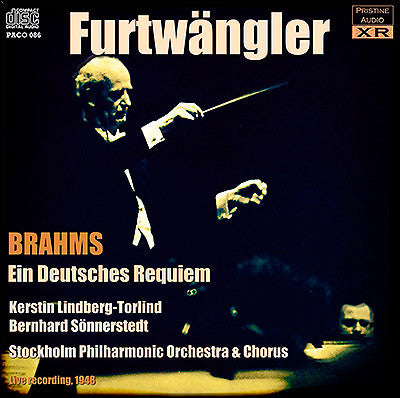

Furtwängler's only complete recording of the Brahms German Requiem

Fabulous sound quality extracted from this live 1948 performance in new XR remastering

One can understand the decision, commented on by The Gramophone's reviewer in 1972, for the original LP issue of this recording to span four sides. Normally one has no difficulty fitting Brahms' Ein Deutsches Requiem onto CD - Mengelberg in 1940 completed it in just under 66 minutes (PACO012). Here I've had to cut quite savagely into the inter-movement gaps, helped by an accurate tuning reading of A4=447Hz drawn from residual mains hum in the recording, in order to just squeeze this into the 80 minutes of a single CD without misrepresenting the musical performance. At normal concert pitch, with the original gaps (with the usual audience coughs), it ran to nearly 85 minutes.

This is the only complete Furtwängler German Requiem, and I've been able to make great strides in terms of sound quality in this new 32-bit XR remaster, helped in no small part by the donation of an unplayed, mint-condition copy of the original Unicorn LP on which it was first issued, for which we are most grateful.

Andrew Rose

-

BRAHMS Ein Deutches Requiem

Live performance at Stockholm Konzerthus, 19 November 1948

Transfers from Unicorn WFS 17/18

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, November-December 2012

Front cover artwork based on a photograph of Furtwängler

Total duration: 79:57

Kerstin Lindberg-Torlind soprano

Bernhard Sönnerstedt baritone

Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra

Stockholm Philharmonic Chorus

Wilhelm Furtwängler conductor

In establishing Furtwängler's importance in the

history of interpretation, the Unicorn label has done sterling service.

Here is another historic performance, inevitably flawed, and not very

well recorded (presumably from radio considering the lightness of bass).

But devotees of Furtwängler will take such points for granted and

relish the chance to study the master's insight into a work which by

nature one would imagine him specially suited.

The results are

not quite what I expected. Much of the phrasing is magical, but I

imagine it would have been even more flexible had he been conducting one

of his regular orchestras. Even so the phrasing at the beginning of the

second movement "Denn alles Fleisch" has all the affection one could

want, and I have never heard the brief introduction to the great soprano

solo, "Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit", played with such tenderness. The

tempo there is exceptionally slow - a severe test for the soprano,

Kerstin Lindberg-Torlind, whose light high soprano (initially

disappointing) then expands well rather in the manner of Grümmer. There

are other slow tempi too, but i t was surprising to find "Wie lieblich"

taken on the fast side with comparatively simple, unpointed phrasing as

though it was a folk-song - very natural and fresh with a

spontaneous-sounding stringendo in the middle.

The

pull of urgency natural to a live performance is very clear indeed, but

from Furtwängler I expected a degree more religious dedication. I

naturally went to Kempe's Berlin performance (still available on HMV

Concert Classics- mono XLP 30073-4, 4/67) and there I found extra

intensity in the first movement, not just in the sustained pianissimos but in the outbursts on the word "Freuden". But then where Furtwängler scored supremely was in the second movement on the fortissimo cries of "Denn alles Fleisch" which have a bitterness, an agony I have never registered before to such a degree.

The soloists have the best deal of all from the recording engineers. I

have already mentioned Lindberg-Torlind. Bernhard Sonnerstedt has a

light high baritone, beautifully focused. Next to a singer like

Fischer-Dieskau his style may sound almost naïve, but I found his fresh,

completely unmannered approach delightfully convincing, with an

underlying Biblical strength. The choral sound, I am afraid, is

generally rather muzzy by comparison, but those who buy this record will

almost certainly know what to expect. It is a pity the Requiem was not fitted (as is usual) on three sides, and a fill-up provided.

E.G., The Gramophone, May 1972 - review of first LP issue

Fanfare Review

This is weighty, flexible, old-fashioned conducting in the very best sense of those words

Andrew Rose is now competing with himself as a transfer engineer. He produced an excellent prior transfer of this performance on Music & Arts—the third on that label, each an improvement over its predecessor. I reviewed that transfer in Fanfare 32:5 (I had reviewed an earlier incarnation of the performance in 12:6). However, he has continued to experiment and improve new techniques, and this one is quite a bit more satisfactory than the Music & Arts edition.

The performance is as I described it in 32:5, and those interested can seek out the review in the Fanfare Archive. This is weighty, flexible, old-fashioned conducting in the very best sense of those words. If your ideal in Brahms is Gardiner or Harnoncourt, and you feel that is the only way to do this music, you probably will not find much to love here. At 80 minutes, this is one of the slowest German Requiems on disc—but never does it drag, because of the constant sense of forward motion. It is Brahms’s harmonic plan that motivates Furtwängler; dynamic, tempo, inflection, and phrasing decisions are always shaped by the harmonic direction and change inherent in the music. The baritone is fine, the soprano starts out unsteadily (and at times out of tune) but gets better as she goes on. But the performance sweeps the listener along with its raw power. It is the only complete Furtwängler performance we have of this work. Other recordings of live performances have chunks missing and virtually unlistenable sound.

You have to be willing to tolerate the sonic limitations here too, but they are not at all as bad as those other versions. Even with Rose’s best work yet, and a fuller, richer orchestral and choral sound than has been available before in this live recording, one is aware of the distortion and sense of compression at climaxes, and the limited frequency response at both ends of the spectrum. Carefully produced studio recordings were being produced at a notably higher level in 1948. Rose made his transfers from Unicorn LPs, and has come up with a result that any listener used to historic material will certainly find more than tolerable. The improvement over his earlier Music & Arts transfer is certainly audible, though whether it is dramatic enough to warrant replacement will depend on your budget and your taste. As someone deeply in love with this performance, I am glad to have the new version.

Henry Fogel

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:6 (July/Aug 2013) of Fanfare Magazine.