This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track & Cast Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

The première recording of Mussorgsky's rarely-heard opera

First of only four known recordings - new XR-remastered transfer

This is the second of two rare Russian opera recordings by the Slovenian National Opera which came my way from the collection of the former art director of Philips UK. It was sold as a boxed set of two LPs; in this case I was working from white-label test pressings for these transfers and had no notes or indication of where anything started or finished.

This lack of information turned out to be one of the greatest challenges, and it took a while to track down an alternative copy of the recording which I could both download as a reference and use to work out where the acts began and ended! Thus the tracks here are more or less split using the template of a mid-1990s recording by Yevgeni Brazhnik, and I've had to do what I can with the badly-translated Russian titles provided with that release, the most recent of only four complete recordings of this opera.

As the Gramophone reviewer points out, the version heard here is that completed by Shebalin in 1931, which is fortunately also used by all the other recordings to date. Unfortunately the score I tracked down, and which is included in the downloads, is an earlier version completed by Cui in 1917, which diverges from the recording in a number of places, not least the entire relocation of the Dream section to the third act.

This Dream music had been adapted by Mussorgsky from his earlier composition, Night on the Bare (or Bald) Mountain. Ironically the version we know now of that piece is one which Rimsky-Korsakov adapted from Sorochyntsi Fair! As I had space left over I took the opportunity to add Willem van Otterloo's 1958 recording of this, together with the flip side (Borodin's Polovtsian Dances) to the second disc of this set for comparison.

As far as the recording quality goes, both recordings were very well made. A side effect of the non-staged style of the opera as noted by Gramophone's 1957 reviewer is that all the words are exceptionally clear and well captured and nobody singing away from the microphones - as I've failed to find a libretto and the score is in Russian script, this may prove handy to the listener! What was less welcome in Sorochyntsi Fair is the prevelance of pre- and post-echo throughout the recording, something which took a great deal of time and effort to eliminate.

Overall, however, both recordings here have come up very nicely indeed, and are excellent examples of the progress made in sound quality during the 1950s. XR remastering has helped bring them forward a decade or two, and I recommend the Ambient Stereo issues.

Andrew Rose

Cast

Cherevik - Latko Koroshetz

Khivria - Bogdana Stritar

Parassia - Vilma Bukovetz

Kum - Friderik Lupsha

Gritsko - Miro Branjnik

Afansy Ivanovich - Slavko Shtrukel

Gypsy - Andrei Andreev

Chernobog - Samo Smerkolj

Slovenian National Opera Orchestra & Chorus

conducted by Samo Hubad

World première recording, 27th November 1955, Salle Apollo, Ljublhana

Transfer from Philips 12" white label test pressings ABL 3148-49

Vienna Symphony Orchestra

Der Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Vienna

conducted by Willem van Otterloo

Recorded at Grosser Saal, Musikverein, Vienna, 23 February 1958

Transfer from Fontana 10" white label test pressing EFR 2012

Transfer 1. Studio recording from 1955, from Philips white label test pressings ABL.3148/49

Transfer 2. Studio recording from 1958, from Fontana white label test pressing EFR 2012

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, September-October 2010

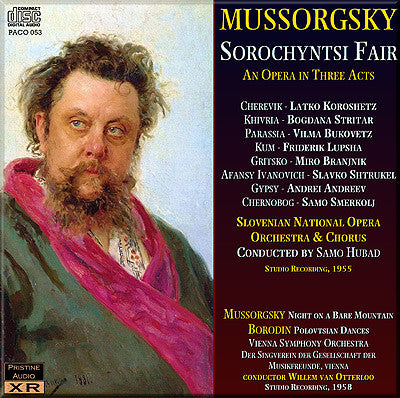

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Mussorgsky

Total duration: 2hr 6:09

"Whenever one comes up against a Russian stage work, the first thing is to establish who composed it ; for it often seems as if the main occupation of Russian musicians is writing each other's operas-after which everyone quarrels and claims it would be better another way. The habit of leaving works incomplete—whether through illness, loss of interest or plain indolence—seems to have been endemic among the famous nineteenth - century Russians ; so that it should come as no particular surprise to learn, from an admirably comprehensive accompanying note by Paul Lamm, that Mussorgsky's Sorochintsy Fair has had to be orchestrated and completed by Liadov, Karatygin, Cui, Tcherepnin and, finally, Shebalin, whose version is the one here employed.

The story—a grotesque one, full of digressions and typically Russian muddles-is set in the Ukraine, whose national musical characteristics are mirrored in the score. Some form of lifeline, either the complete libretto (available for an extra 7s. 6d.), or the detailed account of the plot in the booklet issued with the discs, is absolutely imperative if anything whatever is to be made of this work. For, though the lyrical passages are easy enough to bang on to, the - music of the broad humorous parts is scrappy to a degree ; and it must be admitted that, attractive as are some of the melodies, their treatment is frequently very crude and thin. Only two sections are likely to be known to most people—the final Gopak and the Night on the Bare Mountain, which reappears here in a choral version to accompany the scene of Gritzko's nightmare.

The piece is played with gusto by the Ljubljana company, and the sheer high spirits they bring to it are infectious, even while one recognises the shortcomings in the performance. The orchestra is enthusiastic rather than polished, and the chorus very rough indeed, but the soloists are, many of them, of a high calibre. At the top of the list I would put Mme Stritar as the discontented scold and the tenor Shtrukel, who proves himself a first-rate character comedian, in the part of her gluttonous paramour. Their comic lovescene in Act 2 is a joy. The Parassia—a small part—is good, and the Gritzko has a suitably young-sounding ringing tenor. The Cherevik is too often careless about the exact pitching of his notes.

The recording has been made as if from a concert performance, with little suggestion of stage perspective or dramatic placing of the voices, and one cannot help regretting that for so unfamiliar a work (which, so far as I can recollect, has not been seen in this country since Jay Pomeroy's production at the Cambridge 'Theatre in the early days of the war) more attention was not given to production ". Those with perfect pitch must also steel themselves to transposing the recording down a semitone mentally. Still, as a curiosity, this recording is well worth hearing."

- The Gramophone, November 1957

Fanfare Review

Rose ought to be awarded a gold medal, not only for his restoration work here but for restoring this undeservedly obscure recording to the active catalog

Whereas Mussorgsky completed Boris Godunov and left a virtually complete piano score of Khovanshchina, his short comic opera Sorochyntsi Fair (or Fair at Sorochintsk, as it is sometimes translated instead) remained in fragmentary condition at his death, with a few passages orchestrated, several others completed in piano score, and the remainder existing only as sketches or text. (The most fully completed bits are portions of the first act and the first part of the second.) For whatever reasons, Rimsky-Korsakov declined to occupy himself with a realization of the score; it was then entrusted to Anatoly Liadov, who produced orchestrations of only five numbers before dropping the project. With spoken dialogue bridging between these, the work received a private performance in 1911 in St. Petersburg, followed by a public staging in 1913. César Cui then produced the first truly complete version, including interpolations composed by himself, which was produced in Petrograd (the renamed St. Petersburg) in 1917. Nikolai Tcherepnin then created the first complete edition based solely on Mussorgsky’s own sketches, which received its premiere under his baton in Monte Carlo in 1923. The conductor Nikolai Golovanov next followed with his own version, first given at the Bolshoi in Moscow in 1925. Finally, Vissarion Shebalin, following a thorough study of Mussorgsky’s manuscripts, fashioned what has become the universally accepted version of the score, which received its premiere in 1931 in Leningrad under Samuil Samosud.

As I could not locate any copy of a libretto, and none of the three complete sets I accessed provide one, here is a detailed summary of the plot, which is drawn from a short story by Nikolai Gogol. (Note that while I have preserved the variant transliteration of the opera’s title in the headnote for online search purposes, I have conformed its spelling elsewhere in this review, and that of all the characters’ names, to versions now in general use.) In act I, the Ukrainian village of Sorochintsk is holding its annual fair. Among those in attendance are the peasant Cherevik and his daughter Parasya. In order to buy some of the attractive ribbons and necklaces that Parasya desires, Cherevik must sell some wheat and a mare. A gypsy predicts that the “blood-red jacket,” a legendary article of clothing supposedly housed in a nearby barn, could disrupt the proceedings with its diabolical curse; the superstitious villagers take alarm at his words. The young peasant Grits’ko, who has been courting Parasya, asks Cherevik for her hand in marriage. When Cherevik learns that Grits’ko is the godson of his old friend Kum he gives his consent, and the three men adjourn to the local tavern to celebrate. Later that afternoon, Cherevik and Kum emerge, quite tipsy, and encounter Khivria, Cherevik’s domineering wife. When she learns of the engagement, she vetoes it: She claims that as she drove her wagon across the bridge to enter town, Grits’ko had insultingly flung a handful of cow dung at her face. Grits’ko overhears this and becomes despondent. The gypsy approaches him and promises to assist the young man with his marriage plans in exchange for purchasing the latter’s oxen at a bargain price, a proposal to which Grits’ko delightedly agrees.

In act II, Cherevik is sleeping off his drunken stupor. Khivria, who is conducting a clandestine affair with Afanasy Ivanovich, the son of the local village priest, awakens her husband, picks a quarrel with him, and chases him out of the house, ordering him to sleep under a wagon and keep watch over the wheat and mare that are to be sold. Not even Cherevik’s protests of fear about the curse of the “blood-red jacket” can sway her. Afanasy, an inept bumbler, duly stumbles in, and gorges himself on food while enjoying his amorous tryst. Suddenly Cherevik and Kum return with some friends, and Afanasy must hurriedly hide in a hammock. Cherevik is still fearful of the “blood-red jacket,” although Kum and Khivria try to put him at ease. Finally, Kum relates the story of the jacket. A demon, exiled from Hell for committing an offense against Satan, wandered the earth in boredom and took to drink. Having spent his last kopek, the demon finally pawned his red jacket to an innkeeper, promising to redeem it in a year and warning that it should be well guarded in the interim. Tired of waiting for his mysterious guest to return, the innkeeper sold the jacket. A year later, a stranger returned to demand the jacket; the innkeeper feigned ignorance of any such article, and the stranger disappeared. However, when the innkeeper went to bed that night, pig snouts suddenly appeared in all the windows of the inn, whips materialized, and the innkeeper received a sound thrashing. Since then, the demon searches for his jacket each year at the Sorochyntsi Fair. At this juncture, a window suddenly bursts open and a huge pig stares through it into the room, causing everyone inside to flee in panic.

In act III, Cherevik and Kum are stumbling down the street in confusion; some local youths take them for thieves and handcuff them. Grits’ko and the gypsy appear; the former promises to free the duo if he is granted Parasya’s hand in marriage, to which Cherevik consents. Grits’ko fulfills his pledge to sell his oxen to the gypsy. Tired, he falls asleep beneath a tree, and has a long dream of a witches’ sabbath conducted by the demon Chernobog. (In a somewhat different guise, this music is far better known as the tone poem A Night on Bare Mountain. Mussorgsky originally intended it to form part of act I, but the various editors of his manuscripts relocated it to here instead.) Meanwhile Parasya, grieving for her broken engagement, tries to cheer up by dancing the hopak, and is joined by her father. Grits’ko and Kum arrive, and Cherevik joins the hands of the young lovers to unite them in marriage. Khivria enters and makes one last attempt to thwart the union, but is dragged away by a group of youths to general laughter. The gypsy invites everyone to join in dancing the hopak in a concluding celebration.

To my surprise, there are no previous reviews of any of the four extant recordings of Sorochyntsi Fair, of which this is the earliest. The three subsequent recordings are a 1969 Melodiya recording with the USSR Radio Symphony and Chorus under the baton of Yuri Aranovich, which had its only CD release on a brief-lived Melodiya/Eurodisc issue in Germany; a 1983 version on Melodiya/Olympia with the Stanislavsky Theater ensemble led by Vladimir Esipov, also long out of print; and a 1996 set on the URAL label conducted by Evgeny Brazhnik, reviewed elsewhere in this issue as part of a collection of Mussorgsky’s works reissued on the Brilliant Classics label. With the exception of Vladimir Matorin as Cherevik in the Esipov version, none of the singers in any of these sets has any significant general name recognition. Unfortunately, I have not heard the Esipov (which, according to a description by a seller of a pricey used copy on Amazon, does come with an English-language only libretto).

Of the three versions I have heard, this one is, to my considerable surprise, easily the top choice. As all three are atmospheric and characterful, with fine conducting and choral work, the difference in ranking comes down to the singers. While this is a work in which effective characterization counts for more than beautiful singing, this recording is distinguished from its rivals by its total superiority on the latter count. As Parasya, Vilma Bukovetz has a light, sweet lyric soprano with that extra degree of body common to Slavic singers. Bogdana Stritar has a beautiful mezzo-soprano with a seamless legato and not a trace of acidulousness, that would be too beautiful for the character of Khivria if she were not so adept at varying it for her character’s moods. As it is, she is the one singer of that role who makes her act II arioso a true love song. The two tenor parts of Grits’ko and Afanasy Ivanovich are cast from strength; both Miro Branjnik and Slavko Shtrukel have suave, lyric tenor voices that would do credit to roles such as Jeník in Smetana’s The Bartered Bride or Lenski in Tchaikovsky’s Evgeny Onegin. It is remarkable that such a fine voice is lavished on the role of Afanasy, which normally would be (and on other recordings is) given to a nasal-voiced comprimario tenor; here the stronger casting makes him a more creditable lover. As Cherevik and Kum, Latko Koroshetz and Friderik Lupsha both have wonderfully firm, rich, liquid basso voices, that of Lupsha being a shade darker—what a marvelous recording of Boris Godunov this pair could have made! In the two supporting baritone roles, Andrei Andreev as the gypsy has a light-timbred baritone with just a touch of hollowness, whereas that of Samo Smerkolj as the demon Chernobog is appropriately darker, more rough-hewn, and devoid of legato. All of the singers, and also the excellent chorus, give a scrupulous attention to clarity of diction that is most welcome. If the conducting of Samo Hubad is less earthy than that of his rivals, he lavishes a beautiful lyricism on the score that makes it sing like a troubador’s recounting of a beloved local legend. The orchestra has a lovely burnished string sound that recalls the Vienna Philharmonic and Gewandhaus ensembles, and its members play their hearts out here. Indeed, that a regional opera company, in what would have been cavalierly dismissed as a cultural backwater, could produce a recording of such outstanding merit both vocally and instrumentally, is a standing rebuke to a multitude of major opera houses and recording companies that for years now have foisted on the public an interminable succession of stagings and recordings showcasing highly touted singing mediocrities with nondescript voices and faulty technique who substitute artificial histrionics for genuine vocal interpretation.

Equally worthy of note is the top-notch recorded sound of Andrew Rose’s exemplary transfer from Philips mint-condition test pressings. While I (like virtually everyone else reading these lines) have never heard the original LPs, I can say that, based on having heard comparable pressings of recordings of the same vintage, he has produced truly marvelous results. The ambiance has richness, body, and color; there is just a touch of treble bias and LP surface noise. The singers do have a clearly differentiated reverberant space around them, which I presume to be inherent in the original source. Rose ought to be awarded a gold medal, not only for his restoration work here but for restoring this undeservedly obscure recording to the active catalog.

As supplements (since the opera lasts slightly less than 100 minutes), Rose has quite appropriately added contemporary Philips early stereo recordings from 1958 of Mussorgsky’s Night on the Bare Mountain and the Polovtsian Dances from Borodin’s Prince Igor. The Dutch conductor, composer, and cellist Willem van Otterloo, who eventually made his career primarily in Australia after being passed over as Eduard van Beinum’s successor to lead the Concertgebouw, is little remembered today, though Challenge Classics did issue a 13-CD retrospective set of his recordings with the Residentie Orkest. He was a champion of late 19th- and 20th-century repertoire, and his interpretive style was Classically oriented, with generally brisk tempos, an emphasis on clarity of instrumental lines, and relatively little use of rubato. These are disciplined, well-proportioned performances, though the fact that they are performed with a then second-tier orchestra is clearly evident in the lack of full-bodied string tone. The Borodin (with the excellent Vienna Singverein singing the choral parts) is the more compelling of the two renditions, but it had the misfortune to be issued at virtually the same time as the classic Beecham account on EMI that surely thrust it into immediate obscurity. While neither recording is competitive with a myriad of modern versions, they nonetheless make fine aperitifs to the main musical course here. Rose’s remasterings have clear, forward sound and quiet backgrounds that make for pleasurable listening. In sum, this release is a triumph that belongs in the collection of every lover of Mussorgsky’s music and devotees of lesser-known operatic repertoire; urgently recommended.

James A. Altena

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:5 (May/June 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.