This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

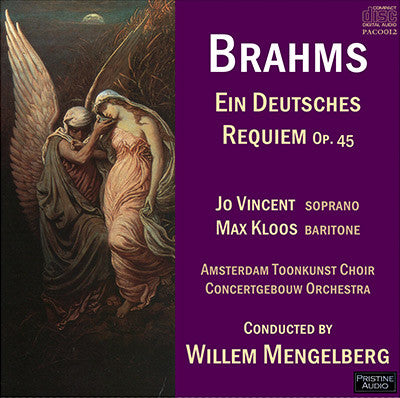

- Cover Art

Fabulous wartime Brahms Requiem from Holland

Mengelberg's live 1940 performance in a superb sonic make-over

Brahms' German Requiem, given its first full performance in Leipzig in

1869, began life over a decade earlier in sketches for a projected first

symphony, which became the first Piano Concerto. It is unclear whether

the death of Brahms' great friend and mentor, Schumann, became the

original impetus for the work; what is clear is that the death of his

mother in 1865 inspired the composer to put his full effort into the

work.

A first performance in 1867, of the opening three

movements, was not a great success - the playing was poor and it was

badly received. Five months later a six-movement version, then intended

to be complete, was given in Bremen Cathedral with the composer

conducting, and his father, and friends Clara Schumann and the violinist

Joachim amongst those present in what was a deeply moving event. The

fifth movement was then added, giving a symmetry and balance to the

whole piece.

At the age of thirty-five, Brahms was finally fully

established as a composer with the success of this piece, and the

proclamation made many years earlier by Schumann, that in Brahms the

world had a worthy successor to Beethoven, began to look possible.

The

text is not drawn from the Catholic Mass, as with a majority of Requiem

Masses set to music at this time; Brahms instead drew on Luther's

German Bible to produce a text designed to console and inspire the

living, rather than offering prayers to the dead. (See below for links

to further detailed information about this piece)

This

recording, made onto acetate 78rpm discs by a Dutch radio station in

1940, was one of a number of Mengelberg's live output that has survived

reasonably well. I say reasonably, as the recording itself was

originally very good, but wear and tear of the delicate and unique disc

surfaces in the twenty years prior to their transfer to tape and then LP

had caused significant damage.

Only very recently has the

technology become available to correct the problems inherent in the

original discs, and by the slow and painstaking application of new

restoration techniques we are now able to present this wonderful

recording in a sound quality far superior to anything heard before.

Andrew Rose

Bill Rosen's Review

There are moments of great choral climaxes in Parts II and VI that are as great or greater than I've ever heard them

The Brahms German Requiem has been close to my heart ever since, as a

college freshman, I sung in it at age 19. We rehearsed it for eight

months under Hugo Strelitzer, an exile from the Nazis who had been an

aide to Richard Strauss. Strelitzer had often prepared the Requiem for

Strauss to conduct; he made it clear that he thought little of our

efforts. We turned to Brahms for solace.

One wonders what

Strauss would have thought of Mengelberg's performance. They were close

and admiring friends. On the one hand, Mengelberg's German Requiem is a

great and a magnificent performance even with the usual Mengelberg

quirks; there are moments of great choral climaxes in Parts II and VI

that are as great or greater than I've ever heard them. On the other

hand, Mengelberg has stuck a knife in his artistic creation that has

wounded but not killed it. More anon.

I Selig Sind

The opening movement is very good, but not great, due to Mengelberg's

typical tempo instabilities. Because of this, the beautiful modulation

at "Sie gehin hin" does not make as great an impact as it could. Still,

there are many beautiful moments.

II Denn alles Fleisch

The opening funeral march is remarkably steady and the choral

fortissimo is shocking and very clear. The trio is lovely and the repeat

of the funeral march is archingly beautiful and forward in movement.

The Handelian fugue that follows is one of the greatest things I've

heard from Mengelberg: entries strong and brilliantly clear;

counterpoint dazzling. Have I ever heard it this good before? And then,

suddenly, it's OVER. I can't believe it. A small poisonous doubt creeps

in--can he have cut it? I don't have a score and I check timings with

other performances and it's within the time limits, so I let it go.

III Herr, lehre doch mich

A superb baritone, Max Klos, opens with "Lord, let me know mine end"

and the chorus is very beautiful in consoling him. And then Mengelberg

does what no other conductor, not even Furtwangler, Toscanini or

Klemperer has done: he conducts the usual murky pedal fugue as if it

were Mozart with great clarity and beauty. Every strand is clear; the

choral fugue above and the unyielding orchestral pedal below. A

magnificent accomplishment.

IV Wie lieblich

This acme of sweetness, this bob-bon is superb and the little contrapuntal acid in the middle cuts it very well.

V I habt nun Traurigkeit

Jo Vincent is not Elizabeth Schwartzkopf in the 1947 Karajan recording of the Requiem and that says it all.

VI Denn wir habel

The great climax of the Requiem. Again Max Klos (nearly equal to Hans

Hotter) opens and Mengelberg creates great mystery and suspense. The

mood finally breaks into tempestuous choral fury. The Pristine Audio

restoration has performed a real miracle here. The choral power is "in

your face"! The final "Death, where is thy sting?" is thrown out like

hammerblows from heaven. I have never heard it with such power. I

understand Strelitzer's contempt for our puny efforts.

Then

the great Handelian fugue begins: "Thou art worthy, o Lord" and again

Mengelberg's mastery of chorus and orchestra is a thing to behold:

clarity, power, unstoppable momentum. And it STOPS!

And I know,

beyond the shadow of a doubt, that he has made a large cut! I search on

the Internet and find two references to large cuts in the 6th movement.

What can one say to such an unbelievable, arrogant artistic blunder?

Cuts have been made to works, of course, to sections that were too long

or where inspiration lagged. But to cut Brahms at the acme of his

inspiration and Mengelberg at the height of his recreation? To me it is

incomprehensible. It suggests to me that Mengelberg's great genius was

mixed with considerable arrogance, that he did not feel as Schnabel did

that "the music is always better than we can perform it".

VII Selig sind

Strong, heavy. It is perhaps now WE who need the consolations of the Requiem.

It is obvious that I feel strongly about the cuts. Even so, this is a

magnificent performance of the German Requiem with miraculous sound

especially in the fortissimo choral pssages. I cannot forbear to listen

to it, even while I realize that Mengelberg lacked the artistic

greatness of a Schnabel, a Toscanini or a Furtwangler.

Reviewer: Bill Rosen