This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

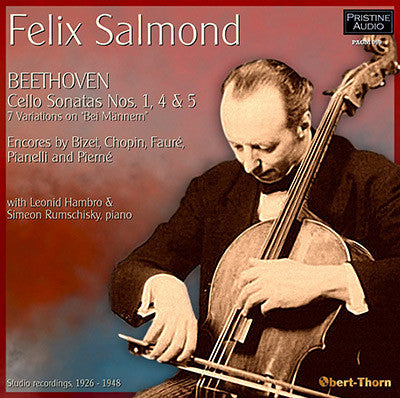

Fabulous hi-fi recordings of Beethoven sonatas from 1948 - first general release

Plus more rare 1920s tracks in their first ever reissue from cello virtuoso Salmond

On March 29, 1947, Felix Salmond gave a recital at the Juilliard School

commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of his American debut. The

program was one he had played on more than one occasion over the years:

the five Beethoven Cello Sonatas. The following year, Salmond and his

performing partner, fellow Juilliard faculty member Leonid Hambro,

returned to the school’s Concert Hall to make a private recording of the

sonatas, three of which were issued in 1960 on a private LP as a

fund-raiser to help establish a scholarship in his name.

These

recordings are revelations in several ways. First, they show that

Salmond maintained his technique even in his sixtieth year. His last

commercial recordings were made in 1930, when he was forty-two; and

although he continued to concertize and appear on broadcasts, these

Beethoven sonatas are the only published documents of his playing after

that.

But more importantly, they present Salmond in the finest

recorded sound he ever received. Except for some occasional surface

noise from the original acetate discs, they have the presence, and

nearly the frequency range, of high fidelity mono tape recordings. The

difference is most striking going from the last sonata to the 1928

recording of the “Magic Flute” Variations which follow it. Here is the

Salmond with which most listeners are familiar – a figure from a shadowy

past, heard dimly through a haze of surface hiss on even the best of

American Columbia’s “Viva-Tonal” pressings.

All of which raises

the question: Why did the record companies ignore Salmond after 1930,

when he continued to play at such a high level? The Depression surely

had something to do with it. For much of the 1930s, Classical

instrumentalists either recorded in Europe or not at all. (Casals, for

example, cut his last disc for Victor in 1928; but HMV was happy to keep

him busy after that.) Due to his teaching positions both at Juilliard

and the Curtis Institute, Salmond’s career by this time was largely

based in the U.S. By the time American labels began recording cellists

again, a new generation had appeared, including Feuermann and

Piatigorsky. Though still active, Salmond was largely forgotten.

It

is posterity’s loss. As critics noted when the first volume of this

series came out (Pristine PACM 095), Salmond’s playing has a decidedly

modern feel, in contrast to the sentimental, portamento-laden

performances of his elder British countryman W. H. Squire. It was an

approach he passed on to his many pupils, including Leonard Rose,

Bernard Greenhouse and Frank Miller, and it can be heard even on the

earliest of the recordings presented here. We are fortunate to be able

to hear him at last not “through a glass darkly” but, in these late

recordings, nearly “face to face”.

Mark Obert-Thorn

BEETHOVEN Cello Sonata No. 1 in F major, Op. 5, No. 1

BEETHOVEN Cello Sonata No. 4 in C major, Op. 102, No. 1

BEETHOVEN Cello Sonata No. 5 in D major, Op. 102, No. 2

Felix Salmond cello

Leonid Hambro piano

Recorded in 1948 in the Juilliard Concert Hall, New York City

First released in 1960 on an unnumbered private LP issued by Juilliard

BEETHOVEN 7 Variations on “Bei Männern” from Die Zauberflöte

Recorded 4 June 1928 in New York City

Matrix nos.: W 14386-1, 14387-4, 14388-4 & 14389-4 (Columbia 179-M/180-M)

PIANELLI (arr. Joseph Salmon) - Villanelle

Recorded 19 April 1926 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 98241-2 (Columbia 7117-M)

CHOPIN Largo from Cello Sonata in G minor, Op. 65

Recorded 5 June 1928 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 146391-3 (Columbia 169-M)

FAURÉ Berceuse (Cradle Song), Op. 16

Recorded 4 June 1928 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 146390-4 (Columbia 169-M)

BIZET Adagietto from L’Arlesienne

Recorded 29 April 1927 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 143184-7 (Columbia 2054-M)

PIERNÉ Serenade, Op. 7

Recorded 29 April 1927 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 144032-6 (Columbia 2054-M)

Felix Salmond cello

Simeon Rumschisky piano

Fanfare Review

It seems greedy (but not churlish) to ask for more ... bring them on

As a successor disc to its first Felix Salmond release, PACM 095 (see reviews in Fanfare 38:4), Pristine Audio releases legendary private recordings of Beethoven’s first cello-piano sonata and his last two in this genre. Various sources had told me these were made just prior to World War II, but that turns out to be in error—off by a decade. Salmond, who played the five works often in recital, gave a concert at Julliard in January of 1947 at which he performed the canon with American pianist Leonid Hambro to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Salmond’s U.S. debut. Mark Obert-Thorn informs us in Pristine’s notes for this release that a year later, the two Julliard faculty members returned to the school’s concert hall to record the works. The three presented here appeared on a private LP in 1960 as part of varied efforts promoting the school. No mention, thus far, of the 1948 recordings of the Second and Third Sonatas. Pristine’s excellent transfer of the cellist’s 1926 recording of the Third leads off the earlier release. Thus we have 80 percent and now a delightful 1928 recording of the “Bei Mannern” Variations, with the same empathetic piano partner as in the Third Sonata. We are making progress, but must still hope that the other two 1948 recordings will surface.

Leonid Hambro (1920–2006) was a notable pianist and a rigorous scholar, in the traditions of such figures as Schnabel, Shure, Serkin, but was utterly unlike those artists in his personal manner and in the range of his performing interests. He recorded Gershwin with the Moog Synthesizer, and performed with Victor Borge. His scholarly bent was more evident in his performances of Beethoven and in his writings with Jascha Zayde. As can be heard in these performances, he was not wedded to the vertical bar lines in which some of the German masters find themselves entangled (Hambro was Chicago-born of Lithuanian-Jewish parents). At age 28, he does not to my ear quite have his older colleague’s innate lyricism. However, my taste runs to performances of these works in which the performers vary a bit in performing styles, and I find Hambro’s Beethoven a distinguished counterpoise to Salmond’s playing. The pianist died less than a decade ago, having served on the Aspen Faculty as well as that of Julliard, and finally as head of the Piano Department at California Institute of Arts. These recordings are as much a tribute to Hambro as to Salmond.

A tribute to Salmond this release is indeed, and to Beethoven as well. In 1948 the cellist’s technique and interpretive concentration were fully intact. The microphone placement of these privately made recordings, in Obert-Thorn’s splendid remastering for Pristine, captures the cello tone superbly. The piano, while ample, does not quite have all the overtones of a current recording, but it will serve. Balance is remarkably good.

The First Sonata lacks nothing in fluency and flow. It may not quite have the charm of the old Janigro-Zecchi recording, or the first Casals set (older still), but it is charming enough, and less serious than Fournier-Schnabel or Casals-Serkin. The zest with which the duo plunges in to the final reprise of the first movement’s allegro theme to conclude the movement is infectious. That zest continues right into the second movement and here the remarkable sound is particularly good at conveying Salmond’s lower partials. The piano seems a bit clearer. Maybe someone moved a mike.

The two sonatas of Beethoven’s op. 102 are among his more enigmatic works, particularly the first (Sonata No. 4) and also possessed of considerable profundity (the Fifth, especially, I would say). Salmond and Hambro take the Fourth Sonata very seriously and play the first movement with great concentration and a consistently steady tempo and drive. I find this the most individualistic interpretation of the three and one of the most persuasive performances of the work I know.

Without making comparisons (odious or otherwise!) Hambro’s opening flourish in the last sonata put me more in mind of Schnabel’s address and command than any I have recently heard. He and Salmond are extremely clear and firm in their articulation of the main lines of this first movement. The depth of lyric feeling in the Adagio is also notable. As I listen, I continually remind myself that Salmond, although not old, has a full career behind him, whereas Hambro is still in the first third of his own long life.

Throughout these recordings, one is totally unaware of them as recording studio products. They sound as performances, and never more so than in the Fifth Sonata. Again, Salmond’s plangent lower string tone is well captured, and in this first movement the piano sound is at its best. One is eager to hear the other two sonatas. I suspect, as much as I love the earlier recording of op. 69 (one of my favorites), the performance with Hambro will be a quite different matter—remembering, too, that over two decades had passed.

Still, Obert-Thorn is unduly harsh on himself and on Columbia (God knows, as one who lived through Columbia 78s and early LPs, it is easy to be hard on them!). His transfer of the June 1928 recording of the lovely variations on Mozart’s aria, while clearly of an earlier vintage than the sonatas, does not fall unattractively on my ear. It is, not unexpectedly, similar to the performance of the third sonata recorded 30 months earlier with the same pianist. I love the piece and this is a charming rendition.

The five remaining encore pieces, also with Rumschisky at the keyboard, include one selection which is rather more than that: the Largo from Chopin’s op. 65 Cello Sonata. This lovely bit leaves me wanting the entire work (recalling the terrific Grieg Sonata included in PACM 095) but we take this, recorded the day after the Beethoven Variations, as all we are going to get. An arrangement of Pianelli’s Villanelle from 1926, Faure’s op. 16 Berceuse (recorded same day as the Variations), and an excerpt from L’Arlesienne, are followed by Piernè’s op. 7 Serenade, both products of an April 1927 session to complete. Despite Obert-Thorn’s criticisms, his sonic resuscitations here are amazing; better to my ear than some on the earlier disc.

It seems greedy (but not churlish) to ask for more, yet if Andrew Rose and/or Mark Obert-Thorn have any further Salmond items, bring them on; specially the other two Beethoven sonatas from 1948. Julliard must have those 78-rpm acetates stored somewhere, or were they done on tape? From the quality of this issue, it might have been possible. James Forrest