This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

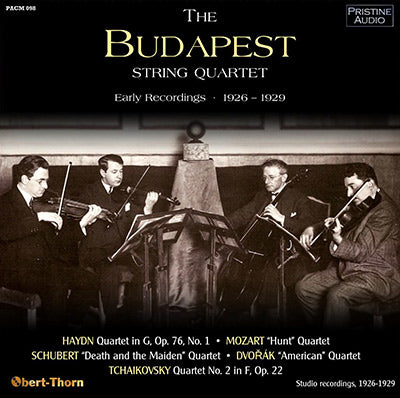

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

A superb collection of early electrical recordings by the Budapest Quartet

"I do not hesitate in saying that this recording of the D minor Quartet is the best I know of" - The Gramophone

“One Russian is an anarchist. Two Russians are a chess game. Three

Russians are a revolution. Four Russians are the Budapest String

Quartet.” Or so went the witticism attributed to Jascha Heifetz. But

this was not always the case. In 1917, when four players from the

Budapest Opera Orchestra formed the quartet, it consisted of three

Hungarians (Emil Hauser, Alfred Indig and Istvan Ipolyi, all Hubay

pupils) and a Dutchman (Harry Son, who had studied with Popper). The

ensemble was founded upon certain ground rules: unusually for the time,

the members would confine their activities only to the quartet; and

interpretational disputes would be resolved by majority vote, with ties

broken by a designated repertoire specialist.

When Indig left in

1920, he was replaced by another Hungarian, Imre Pogany. It was this

configuration which first entered the recording studio in 1924. HMV

producer Fred Gaisberg was keen to compete with Columbia’s

Budapest-based Lener Quartet. Acoustic sessions devoted to the Dvořák

“American” Quartet came to nought when electrical recording was

introduced in 1925, and the ensemble’s first issued recordings, all of

which are presented here, date from a series of sessions dating from

January through March of 1926.

The Russian infiltration began in

the latter half of the following year. Pogany had left to join Fritz

Reiner’s Cincinnati Symphony (he would later move on to Toscanini’s New

York Philharmonic) and was replaced by Odessa-born Joseph Roisman.

Roisman had studied in both his native city and Berlin, and brought a

different approach that from early on challenged the Hungarians’ status

quo (including their playing of weak staccatos using the tip of the bow,

rather than its middle).

In 1930, Harry Son left the quartet and

moved to Palestine. (He was later to return to Rotterdam, ultimately

becoming a victim of the Holocaust.) His position was taken in 1931 by

the second Russian, Mischa Schneider. Roisman now found an ally in his

interpretive disputes, and by 1932, Hauser decided to leave, selling his

Guarnerius to Roisman and eventually becoming a well-regarded teacher,

both in Israel and the United States. With Roisman now as leader,

Alexander Schneider, Mischa’s brother, was engaged for the second violin

spot. Ipolyi soldiered on for several more years before leaving in

1936 to be replaced by another Odessa native, Boris Kroyt. He became a

teacher and author, eventually settling in Norway.

The early

quartet’s recordings have had only spotty availability in extended-play

format. Their 1927 Beethoven Grosse Fuge appeared on an EMI Références

LP and a Biddulph CD. The latter also contained nearly all the rest of

the quartet’s Beethoven recordings, including Opp. 130 and 59/1. A CD

on the Novello label featured the Schubert, Mendelssohn, Borodin and

Dvořák presented here, along with the “Andante cantabile” from

Tchaikovsky’s First Quartet. The Haydn, Dittersdorf, Mozart and

Tchaikovsky Second Quartet make their first appearances here since the

78 rpm era.

The sources for the transfers were mostly prewar

American Victor editions: “Z” pressings for the Dvořák and Tchaikovsky;

a “Gold” label album for the Schubert and Mendelssohn; and

“Orthophonic” pressings for the Mozart and Borodin. The Haydn and

Dittersdorf were taken from British HMV shellacs.

Mark Obert-Thorn

HAYDN Quartet in G Major, Op. 76, No. 1

Recorded 21 January and 4 and 11 February 1926

Matrix nos.: Cc 7787-1, 7788-2, 7835-2, 7836-1 & 7837-5 (HMV D 1075/7)

DITTERSDORF Allegro (Finale) from String Quartet No. 1 in D Major

Recorded 4 February 1926 ∙ Matrix no.: Cc 7840-1 (HMV D 1077)

MOZART Quartet No. 17 in B Flat Major, K. 458, “Hunt”

Recorded 25 January, 1 and 8 February and 4 March 1926

Matrix nos.: Cc 7854-2, 7855-1, 7856-2, 7857-7, 7858-7A & 7859-2 (HMV D 1387/9)

DVOŘÁK Quartet No. 12 in F Major, Op. 96, “American”

Recorded 16 February 1926

Matrix nos.: Cc 7769-5, 7770-5, 7771-4, 7772-5, 7773-5 & 7786-5 (HMV D 1124/6)

Emil Hauser (Violin I)

Imre Pogany (Violin II)

Istvan Ipolyi (Viola)

Harry Son (Cello)

Recorded in the HMV Studios, Hayes, Middlesex

BORODIN Nocturne from Quartet No. 2 in D Major

Recorded 23 January 1928 ∙ Matrix nos.: Cc 12466-2 & 12467-2 (HMV D 1441)

SCHUBERT Quartet No. 14 in D Minor, D.810, “Death and the Maiden”

Recorded 23 and 26 January 1928

Matrix nos.: Cc 10160-3, 10161-3, 10162-2, 10163-6, 10164-7, 10165-4, 10166-5, 10167-5 & 10168-5 (HMV D 1422/5)

MENDELSSOHN Canzonetta from Quartet in E Flat Major, Op. 12

Recorded 23 January 1928 ∙ Matrix nos.: Cc 12465-1 (HMV D 1425)

TCHAIKOVSKY Quartet No. 2 in F Major, Op. 22

Recorded 8 and 9 February 1929

Matrix nos.: Cc 15861-2A, 15862-2A, 15863-1, 15864-1A, 15865-2, 15866-2A-T1, 15867-1, 15868-2 & 15869-1A (HMV D 1655/9)

Emil Hauser (Violin I)

Joseph Roisman (Violin II)

Istvan Ipolyi (Viola)

Harry Son (Cello)

Recorded in Studio C, Small Queen’s Hall, London

Schubert, 1928

It gives me a feeling of great pleasure when from

the Editor I receive a big album containing some musical work in its

entirety. And when this time I read the title and saw that H.M.V. had

recorded Schubert’s String Quartet in D minor (“Death and the Maiden”)

performed by The Budapest String Quartet (D. 1422—26, 12in., in album,

£1 12s. 6d.), my heart leapt, knowing that something really good was in

store for me—and I was not disappointed.

Schubert is to me, first

of all, the composer of the lieder of the world: but when they have

been mentioned I turn to the two well-known Symphonies, the Quintet with

the two ’celli and this Quartet in D minor. All four works have the

main Schubertian qualities in common—the spontaneous well of musical

ideas, the flow and the joy, but also such grave problems as it is only

given the great ones to meet with and to solve in their inmost mind. To

create such music means unselfishly to serve the ideas and never to stop

before the last and only expression has been found. To perform such

music means just the same, and that is why I do not hesitate in saying

that this recording of the D minor Quartet is the best I know of.

It

is not necessary but, nevertheless, stimulating to compare it with

another gramophonic edition, namely, the excellent performance by the

London String Quartet (Columbia) which also is electrically recorded.

Now, electrical recording steadily improves and the Budapest String

Quartet benefits from it. All five discs are exceptionally fine from a

gramophonic point of view. But, what is far more important, this

performance is unselfishly Schubertian. It has obviously been the aim of

these performers not to show their fine playing but to play Schubert’s

fine Quartet. The L.S.Q. has much of this but the Budapestians have

more, and anyone who will listen to the theme of the second movement

(the “Death and Maiden” subject where, by the way, only “Death” appears)

will realise what I mean. Many will find that the L.S.Q. have mere

delicacy, but the B.S.Q. have a broader attack and are of a more vivid

temperament (listen to the last movement) and, as I pointed out last

month, have a more “ quartettish ” way of playing than many bodies,

where one player is mostly predominant. I put them amongst the very best

quartet players of the present time, and they have done themselves and

H.M.V. full justice on this occasion.

C. J., The Gramophone, May 1928

Audiophile Audition review

Convincing, colorful bravura from the Budapest ensemble

Assembled from electrical inscriptions, 1926-1929, this extensive set dedicated to The Budapest String Quartet (1917-1967) concentrates on the ensemble’s early years, when shifts in the originally Hungarian ensemble had not yet resulted in an all-Russian personnel. The Quartet members – Emil Hauser and Imre Pogeny, violins; Istvan Ipolyi, viola; and Harry Son, cello – established a homogeneous, albeit Old-World sound – listen to their Borodin Nocturne – while having instituted a democratic process for the selection of repertory. By the 1928 inscriptions, Russian violinist Joseph Roisman had already “infiltrated” the group in the second violin position. Recording producer and engineer Mark Obert-Thorn notes that the works by Haydn, Dittersdorf, Mozart, and Tchaikovsky appear for the first time in the CD format, not having been reissued since their 78 rpm incarnation.

The Mozart “Hunt” Quartet from 1926 presents a fine example of the Budapest style at the time, with often deliberate, slowly articulated phraseology – particularly in the Menuetto movement – and a high thin, reedy sound from Emil Hauser. The “period” aspects of the Romantic style – rubato, hefty vibrato, and portamento – emerge rather par for the course. The clear articulation in the Adagio movement simultaneously emphasizes Mozart’s long, interweaving melodic lines and their passing harmonic audacities. Harry Son’s cello part adds a piquant lyricism to the whole. The fleet Allegro assai, for all its concertante brilliance, proffers passing, ghostly harmonies touched by a sense of personal anguish.

The last movement of Dittersdorf Quartet in G (1926) clearly “borrows” motifs from Haydn’s Symphony No. 88 in G, the final movement. But the playing, like that of the Haydn, also from February 1926, proves so infectious that we care not whether allusion or plagiarism operates here. The Dvorak performance from 16 February 1926 obviously predates the Russians’ CBS LP (ML 5143) which I owned and became my staple recording. Here, in their Hungarian guise, the players lilt and inflect Dvorak’s already sentimental lines in the Lento with a studied treacle that might not agree with contemporary tastes. Yet Emil Hauser and Imre Pogeny make a convincing duet against the ostinato figures in the bass line. The Scherzo moves in rather pesant figures, studied and tensely ponderous, with another of those “ghostly” effects proffered in the Trio, aligning Dvorak more with Weber and the dark Romantics. Only the exuberant Finale retains a jovial character, a radiance allotted to this vivacious dance music that had eluded the earlier movements. The caesura in the flow of the line makes us think that Mengelberg led this performance! For Disc 1, the forever lovely Nocturne by Borodin (23 January 1928) makes a perfect encore, especially for the artistry of the two low instruments, courtesy of Ipolyi and Son.

Curiously in the 1950s CBS LP of “Budapest Quartet Encores” (ML 5116), only the Borodin and Mendelssohn Canzonetta had renewed inscription from the all-Russian ensemble. That disc made us wish for a complete version of the Franck Quartet in the Budapest pantheon of recordings. With Roisman in the second violin chair, we might grant a degree of crisper, cleaner articulation In the Mendelssohn (23 January 1928) than we had been hearing in the 1926 shellacs. I recently aired the recording of the 1874 Tchaikovsky F Major Quartet, an opus the composer held in high esteem. The February 1929 recording has been restored with disarming clarity of line, so the music’s diverse virtues shine, as the opening quasi cadenza sets a powerful mood. The interior movements’ asymmetries emerge in well defined sonics. Typically, Tchaikovsky invokes contrapuntal means in the last movement to “legitimize” his Classical credentials. Given Tchaikovsky’s admiration of Beethoven – “there are no wasted motions in his music, no filler,” exclaimed Tchaikovsky – it seems appropriate that much of this quartet – especially in the metrics of the Scherzo – resonates with a confidence and sense of structure associated with the Bonn master.

From the opening, macabre fanfare, the Budapest Quartet’s inscription (January 1928) of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden Quartet of 1826 bears the imprimatur of a fine performance. Only the “Death” lyric of the Matthias Claudius poem is cited by Schubert from his own song, from which the g minor second movement draws its impetus. The rhythm bears a family resemblance to the Allegretto of the Beethoven Seventh Symphony. Of the variations that follow, only the fourth permits a ray of sunshine in G Major; but prior to that hopefulness, Emil Hauser has intoned some fine lyricism, along with Son and Ipolyi.

The last two movements exploit a more “symphonic” sound, so no wonder Mahler found the entire work worthy of orchestral treatment. The haunted character of the Scherzo does little to relieve the immanence of Death. Is the Trio section anything more than a seduction of the Maiden by Death, in the same vein as the Elf-King’s overtures to the sickly boy in Der Erlkoenig? The combination of hunting-motif and eerie tarantella of the last movement offers a Presto of convincing, colorful bravura from the Budapest ensemble, here posing a serious rival to the equally respected inscription by the Busch String Quartet.

—Gary Lemco