This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Fanfare Review

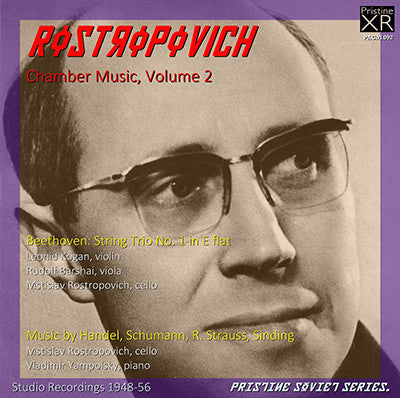

More brilliant and rare Soviet chamber music recordings by Rostropovich

Beethoven String Trio with Kogan & Barshai, plus short pieces by Handel, Schumann, R. Strauss & Sinding

The last-minute discovery of a 1993 Fanfare review answers some questions regarding recording dates with Yampolsky, the initial dullness of which has here been improved upon quite successfully. Elsewhere the reviewer bemoans the incomplete nature of these odd movements. I suspect the recordings were made to fit odd 78rpm sides and the works in question were never recorded in their complete forms. Regardless, they turn out to be older than I imagined, leaving me even more surprised at their inherent sound quality.

One truly bizarre anomaly raised its head: in the fourth movement of the Beethoven a tape edit had been made where a few notes had been spliced in backwards! Naturally this has now been remedied.

Andrew Rose

-

BEETHOVEN String Trio No. 1 in E flat, Op. 3

Leonid Kogan violin

Rudolf Barshai viola

Mstislav Rostropovich celloRecorded Moscow, 1956

Transfer from Melodiya ND 03458-03459 -

HANDEL Violin Sonata in D, Op. 1, No. 13: 3rd mvt. - Largetto

-

SCHUMANN 5 Stücke im Volkston, Op.102: 1. Vanitas vanitatum: Mit Humor

-

SCHUMANN 5 Stücke im Volkston, Op.102: 4. Nicht zu rasch

-

R. STRAUSS Stimmungsbilder, Op.9: 2. An einsamer Quelle

-

SINDING Suite im alten Stil in A minor, Op. 10 - 1st mvt. - Presto

Mstislav Rostropovich cello

Vladimir Yampolsky pianoRecorded 1948 - 1953

Transfer from Melodiya 33D-027827

Rostropovich Chamber Music (Melodiya CD issue, 1992)

From a Western perspective, the political events of the last couple of years are enough to make one's head spin. From an Eastern perspective, they have to be a whole lot more than that. Gosh, how I miss Winston Churchill's wondrous “Iron Curtain.“ It so clearly defined who the enemy was, and gave us all such a compelling sense of purpose. As a product of the postwar McCarthy era, I was duly indoctrinated against the evils of Soviet Communism. It produced a grim, joyless, dour, cultureless society that was best gotten rid of—especially in light of the fact that it was hell-bent on getting rid of us. I dutifully persisted in this politically correct mind-set until I discovered a few ancient and extraordinarily crude LPs released under the imprimaturs of Coliseum and Bruno. They contained standard (and not-so-standard) repertoire stuff performed by then largely unknown Soviet artists. Thus it was that I first heard David Oistrakh, Leonid Kogan, Mstislav Rostropovich, Vladimir Yampolsky, Sviatoslav Knushevitsky, and Kiril Kondrashin. Those recordings were all “produced“ by one Bruno G. Ronty, who, apparently, gained access to a number of bootleg Soviet LPs and used them as sources for the production of his own record line, hence the dismal sound— similar to hearing an LP that had been pressed on wretched vinyl through a bad telephone connection. “How lousy Soviet recording is—“ I concluded;—“Yet another example of Western supremacy and Soviet backwardness.“ On a couple of releases Ronty proudly stated that no moneys from the sale of these records would ever reach their [evil] sources.

One of my prize Coliseum releases of that era is CRLP 179, containing a postwar recording of Lalo's Symphonie Espagnole (with the usually missing Intermezzo) played by a then quite young David Oistrakh and seconded by Kiril Kondrashin—by all measures but sonic excellence, a fabulous recording.

During the ensuing decades other Soviet releases reached the shores of New Jersey via more legitimate channels. A company called Connoisseur Record Corp., in Kearny, NJ, began to release a series of mono LPs from both the MK and Supraphon catalogs. Thus it was, as callow youth, that I first heard the Leningrad Philharmonic under Yevgeny Mravinsky in a performance of Prokofiev's Sixth Symphony. I had never heard the piece before, and that performance (lovingly preserved in eminently decent sound on ALP-158) is, many years and many recordings later, still the one by which I judge all others.

Soviet recordings eventually penetrated the American market via several other Western companies—Monitor, EMI, and later CBS. In our digital era, MCA has issued a number of releases, as has Sheffield Labs (see Fanfare 11:1, “Sheffield Goes to Moscow,“ by Peter Rabinowitz). A few other releases reached our shores on Olympia, and I have in my library one recording on Melodiya Australia (distributed by Allegro Imports). Now, finally, with the collapse of the Soviet Union (and under the duress of having to raise hard currency), Melodiya is marketing its vast, varied, and often distinguished catalog on its own. As a fan of their work over the years, I wish them all the best.

Upon examining these two offerings, I have a few minor, and I hope fairly innocuous, quibbles. Each box proudly states “Made in the USSR.“ In fact, though the recordings and jewel box design are Russian, the CDs themselves were manufactured by American Helix. For a moment I thought that Russia had a CD production facility, but no such luck. The marketing strategy of Melodiya, as demonstrated here, is to exploit the Western name recognition of the major artists involved—Rostropovich, Gilels, Kogan, and (to aficionados of the art of accompaniment) Yampolsky, are all, and have been, well-established figures for years. This approach makes sense, but here it has been executed at the expense of repertoire considerations. On the first disc only two of Schumann's Stücke im Volkston are given. Given performances of this quality, I would have liked to hear the remaining three numbers. I feel it would have been wiser to program the whole set at the expense of the overexposed Kinderscenen excerpt and the Sinding Presto. Likewise, on the second disc, the Larghetto from Handel's Sonata in D, op. 1, No. 13, needs its companion movements in order to be a viable musical experience.

The “star“ of these two releases is Mstislav Rostropovich. The first disc covers his career from 1948 (the Sinding Presto) through 1953 (the two excerpts from Stücke im Volkston)—long before he had become an internationally known figure. The second CD contains performances from 1949 (the Chopin Introduction and Polonaise Brilliante) through 1956 (the Beethoven Trio for Violin, Viola, and Cello). Along the way one can partake of the outstanding work of a comparatively youthful Emil Gilels (forty years old in Beethoven's Trio, op. 97); Leonid Kogan (thirty-two years old in both the Beethoven Trios, op. 3 and op. 97), and of violist Rudolf Barshai before the founding of his Moscow Chamber Orchestra. In all cases, the sound is eminently decent for its vintage.

Beethoven's Trio No. 1 for Violin, Viola, and Cello in E♭, op. 3, and his “Archduke“ Trio, op. 97, are the two main events on these releases. All six movements of op. 3 are given equally robust and sensitive performances—pointed, beautifully intoned, and informed with both vitality and a particularly Russian brand of whimsy. For once this piece of youthful (ca. 1786) Beethoven is given its due.

The “Archduke“ Trio, in the hands of Gilels, Kogan, and Rostropovich, receives an arching, ruminative, and noble reading. Phrases speak with an eloquence they seldom have in the hands of more modern, objective players. All elements—attack, dynamics, and tone color—are brought into play and masterfully exploited in the making of an expansive, quietly heroic performance. This is the tradition that had already produced David Oistrakh and would eventually spawn Yuli Turovsky.

The other pieces, despite their modest dimensions, or overall worth, are all done as if they are the musical end of the world. Of special note is the Villa-Lobos Prelude from Bachiana Brassileira No. 1—here given an intensely dark, brooding, and Russianly manic reading.

As I stated above, the sonics on these two releases are, by Western standards, fine for their respective ages. To anyone familiar only with those old Coliseum and Bruno releases, these samples of late-1940s-through mid-1950s Soviet recording will prove, in this CD incarnation, astonishing. To those familiar with subsequent Soviet releases distributed in the West, these offerings will be more than merely technically competent—they will prove to be musically satisfying.

I hungrily await future releases.

Review by William Zagorski

This article originally appeared in Issue 16:3 (Jan/Feb 1993) of Fanfare Magazine.

The recordings referred to include those on this release and those on PACM090

Fanfare Review

This is great stuff! Strongly recommended

This is great stuff! I’ll admit that for the first minute or so of the Beethoven Trio, recorded in Moscow in 1956 and transferred from Melodiya ND 03458-03459, it sounds like the original recording engineer was twiddling the knobs to try optimize the balance and aural perspective, because first the players sound distant, then close up, then soft, and then loud. But once the sonic image settles into a stable and comfortable place, the performance one is treated to is simply magnificent. Put three of the 20th century’s top Russian string players—Leonid Kogan, Rudolf Barshai, and Mstislav Rostropovich—together, and you were bound to have a surefire success. The sharp definition and unanimity of articulation one hears in the playing are simply amazing; and the up-tempo, intensely focused, and lyrical largesse of this reading—where the music calls for it—lend this early work by Beethoven a stature it doesn’t always achieve in lesser hands.

This is not the same performance of the trio by these three players that was recorded live in 1960 at the Prague Spring Festival, and which can be heard on a Supraphon CD. It is, however, the same performance that was reviewed by William Zagorski in 16:3, when it was released on Melodiya 10-00552. That review may be a bit confusing because it covers two separate CDs (the other being Melodiya 00550), which parses the material differently across the two discs than how it’s programmed on this Pristine release. But if you search out Pristine’s companion to this album, Rostropovich Chamber Music Volume 1, you’ll find some (not all) of the works included on the two Melodiya CDs. Unfortunately, I haven’t heard either of those discs, so I can’t tell attest to how they compare to this “XR” Pristine remastering, but I can attest to the phenomenal results Andrew Rose has achieved for this release.

The remainder of the program is given over to Rostropovich and Vladimir Yampolsky in a sequence of excerpts from larger works, recorded between 1948 and 1953. Three of them, of course—the Handel, Strauss, and Sinding—are arrangements for cello from their original instrumentation. The first movement of the Sinding Suite, a perpetual motion piece, originally for violin, is very effective on cello, and an excellent virtuoso vehicle for displaying Rostropovich’s impressive technique.

This is a most enjoyable album, and another credit to Andrew Rose and his Pristine label. Strongly recommended. Jerry Dubins