This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Sleevenotes

- Historic NY Times Review

"It was a rousing performance ... Mr. Stokowski led a dramatic performance that had special drive and crispness in the scherzo and that built up into a series of big climaxes in the last movement." - New York Times, 1941

Exactly one month prior to the entry of the United States into World War II, on Armistice Day 1941, Leopold Stokowski conducted the NBC Symphony Orchestra in a rare performance for him of Beethoven's Symphony No. 9. As the NY Times reviewer pointed out, "he chose a solemn day in a momentous time to set forth once more Beethoven’s affirmation of the brotherhood of man."

It's a performance that has never been heard in full since. A scheduling anomaly meant that whilst Stokowski performed the entire work before a packed house, radio listeners were treated only to the final choral movement. The first three movements were never broadcast, and as far as we can tell, have not been issued before.

They were however captured in a line recording, from which the present release is largely drawn, and preserved in stunning sound quality for the day. Indeed the finale, which was drawn from a recording of the broadcast (complete with closing commentary), whilst also of fine sound quality, struggles to quite match that heard in the opening three movements.

It should at this point be noted that a very short section at the end of the third movement was missing from the original source recording. We assume that the time recording was faded out at this point in order for the commentator to be heard on NBC radio. For this I have patched in a later recording by Stokowski, digitally aged to match the sound of the 1941 recording and spliced in so seamlessly that two Stokowski experts who heard it prior to release were unable to detect the change. It helped enormously that Stokowski's later performance matched the 1941 tempo almost exactly during that third movement. I have also reconstructed a shorter pause between third and fourth movements than was heard by the audience on the night - an extra delay was caused by the need to go "on air" prior to commencing the finale, as the Times' reviewer noted the following day.

And so we present an entirely new Stokowski performance of the Choral Symphony. As you'll hear from the sample movement (the second) on this page, it really is a stunning sounding performance - and one you won't wish to be without.

Andrew Rose

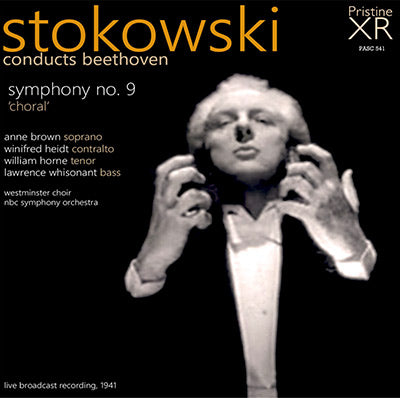

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, 'Choral'

1. 1st mvt. - Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso (13:51)

2. 2nd mvt. - Scherzo. Molto vivace - Presto (10:09)

3. 3rd mvt. - Adagio molto e cantabile (15:08)

4. 4th mvt. - Presto - Allegro assai (24:37)

5. RADIO Closing announcements (2:19)

Winifred Heidt. contralto

William Horne. tenor

Lawrence Whisonant. bass

The Westminster Choir

NBC Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Leopold Stokowski

Cosmopolitan Opera House, New York City

Movements 1-3 not broadcast

Live broadcast recording, 11 November 1941

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Leopold Stokowski

Total duration: 66:04

Leopold Stokowski’s recording career spanned an astonishing sixty years, from 1917 to 1977. Yet in all that time he recorded Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony only twice: in 1934 with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and in 1967 (in stereo) with the London Symphony Orchestra. It was a piece he programmed comparatively rarely in concerts, particularly when compared to Beethoven’s Fifth or Seventh Symphonies. Stokowski had been appointed as principal conductor of the NBCSO for the 1941-2 season and this broadcast was only his second appearance as conductor. In order to allow for acoustical changes to be made, at Stokowski’s instigation, to the usual broadcast studio (8H) the orchestra had decamped to the Cosmopolitan Opera House in New York City. For this new season the broadcasts were moved from Saturdays to Tuesdays, and the length of the broadcast was shortened to just an hour. To complicate matters further, this particular broadcast was only allotted thirty minutes, from 9.30 to 10pm, as from 10pm several networks joined up to broadcast the ‘Red Cross Roll Call’. Beethoven’s Ninth would not have fit into the broadcast hour anyway, so the network decided to broadcast just the last movement, with the first three movements being heard only in the house by the (paying) audience. Fortunately for us, the NBC engineers recorded the non-broadcast movements (most likely for later relay to Latin America).

The New York Times was impressed by a ‘dramatic performance that had special drive and crispness’. Stokowski decided to perform the choral section in English and gathered four young American soloists, all under the age of 30. In an acknowledgement of Beethoven’s theme of universal brotherhood, two of the soloists were African American. Despite Marion Anderson and Paul Robeson becoming very well known, opportunities for black singers remained very limited in the USA and the racial segregation of schools, housing, and public transport was commonplace.

Anne Wiggins Brown was recognised as a prodigiously talented soprano from an early age. She studied at the Julliard School in New York, and while still a student she heard that George Gershwin was writing an opera about black life in the South and she requested an audition. Gershwin was so impressed that he immediately cast her as Bess in Porgy and Bess. She sang in the world premiere and the subsequent US tour. Despite her talent, and relative fame, Brown remained disappointed at the continued racism of US society, at one point refusing to sing Bess in Washington DC until the theatre was desegregated. She eventually left the US to live in Norway.

Contralto Winifred Heidt was at the start of her fairly short career at the time of this broadcast. Although she had been a runner-up at the Met auditions in 1939 her stage appearances with the company were limited to just two Walküres in 1940. After the war she appeared as Carmen with New York City Opera and was a regular concert performer with husband Eugene Conley. In 1954 she appeared on Broadway in Carousel.

Tenor William Horne was only 28 at the time of this broadcast, and (due to a short stint in the army during the war) would not make his stage debut until 1944 with the New York City Opera. In 1946 he sang the title role in the US premiere of Peter Grimes conducted by Leonard Bernstein.

Lawrence Whisonant (also later known as Lawrence Winters) was a still a college student at the time of this broadcast. Like Horne he served in the US army in the war, and he joined both Horne and Heidt at the New York City Opera in 1946 where he sang a number of leading baritone roles. He became the most prominent African American baritone of his generation, performing at the Royal Opera Stockholm, Deutsche Opera Berlin, Hamburg State Opera, and the Vienna State Opera. His US career was certainly curtailed by his race he never appeared at the Met for instance, though he did sing with the San Francisco Opera, and in concerts with the New York Philharmonic.

STOKOWSKI LEADS BEETHOVEN’S NINTH

Westminster Choir Sings the Choral Passages in English With NBC Orchestra

FOUR SOLOISTS ARE HEARD

Lawrence Whisonant, William Horne, Winifred Heidt and Anne Brown Appear

It was probably no coincidence that Leopold Stokowski scheduled Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony for Armistice Day. In presenting the tremendous work at his second concert with the NBC Symphony Orchestra at the Cosmopolitan Opera House last night, he chose a solemn day in a momentous time to set forth once more Beethoven’s affirmation of the brotherhood of man.

Mr. Stokowski made an effort to put the ideal into practice by inviting two Negro singers — Anne Brown, soprano, and Lawrence Whisonant, bass — to join the quartet of soloists. The others were Winifred Heidt, contralto, and William Horne, tenor. The Westminster Choir, which is directed by John Finley Williamson, sang the choral pages. The text was sung in English in the interest of comprehensibility.

It was a rousing performance — what one could hear of it in proper balance. What goes over the air may have the perfection of ensemble tone that a Stokowski orchestra usually commands. These concerts are designed for broadcasting primarily, and if reception in the home does justice to the orchestra more than half the battle is won. The audience in the hall, however, has cause for complaint, for it pays an admission fee, and the bald fact is that the acoustics in this theatre were no better last night than Studio 8-H in Radio City, if not worse.

Making allowances for distortions and coarseness of tone quality, one may say that Mr. Stokowski led a dramatic performance that had special drive and crispness in the scherzo and that built up into a series of big climaxes in the last movement. Because he was going on the air with the beginning of the choral movement, Mr. Stokowski had to pause for a minute or two at the end of the third, which is unfortunate, for Beethoven's logic is better served if the final movement follows immediately.

The members of the choir sat through the performance downstage at the sides, which must have been rather taxing on their nerves during the first three movements when their only task was to sit still. When they sang, they dominated the orchestra, because they were in front. They sang with gusto and fine vocal quality. The soloists managed the difficult music with reasonable smoothness.

During the first three movements, especially the third, the audience was subjected to a prime nuisance that Mr. Stokowski would surely not have tolerated, had he known about it, nor would the NBC management at one of its Radio City studios. Latecomers were ushered in and allowed to clatter and climb to their seats. The great slow movement was not benefited by this treatment.

H. T.

The New York Times

12 November 1941