This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Extended Sleeve Notes

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

- First Night Review

Performances of Claude Debussy’s only opera Pelléas et Mélisande at the Metropolitan Opera have been almost as elusive as the frail, mysterious Mélisande herself. Since its first Met performance on 21 March 1925, just a mere 23 years after its world premiere, the opera has only been performed 114 times to date. That’s a total of 93 years. To put that into context using the ABCs of the opera world, Aïda, La Bohème and Carmen, each reached their 114th performances 21, 12 and 15 years after their first performances at the Met, respectively.

Admittedly, Pelléas et Mélisande doesn’t have the grand choruses and spectacle of Aïda, the blossoming love of two young Bohemians on Christmas Eve in the Latin Quarter of Paris of La Bohè me or the endless tunes of Carmen that audiences flock to see and hear year after year. But what it does have, an ethereal, almost time-evasive quality, is what makes the work so individual and special.

Interestingly, the work was immensely popular in New York from its first performance on 19 February 1908, barely six years after its world premiere at the Opéra-Comique on 30 April 1902. It was presented by the only company to give the Metropolitan Opera its only real competition during this time, the Manhattan Opera Company, run by Oscar Hammerstein l. Where Met General Manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza was able to offer the public truly grand opera with some of the greatest singers of the time (Farrar, Sembrich, Homer, Caruso, Scotti, and Chaliapin, to name just a very few), Hammerstein and the Manhattan Opera Company drew its audiences with its own pool of great singers, but more significantly, somewhat more adventurous repertory, particularly with the French works that the Met was not programming, Pelléas et Mélisande, Louise and the many operas of Jules Massenet, among them.

No doubt, one of the reasons for the success of these early New York performances of Pelléas et Mélisande was the presence of the Mélisande of the world premiere, Mary Garden. It should also be noted that Hammerstein was able to secure the services of the first Pelléas, Jean Périer, Golaud, Hector Dufranne and Geneviève, Jeanne Gerville-Réache, as well for these initial performances. Cleofonte Campanini was the conductor. But it was undoubtably Garden herself, who was known not only for her voice, but for her exceptional acting, that kept the opera in front of the public.

When the work finally arrived at the Met in 1925, it had its own star-studded cast, including Lucrezia Bori (wearing costumes specifically designed for her by the great Russian artist, Erté), Edward Johnson (who studied the role with the roles originator, Jean Périer and who would eventually become General Manager of the Met in 1935), Clarence Whitehill, Léon Rothier and Kathleen Howard. Louis Hasselmans conducted. The opera was performed 32 times in 11 consecutive seasons and has been in and out of the repertory sporadically ever since.

The first broadcast of the opera took place on 21 January 1933 and presented only Acts Two and Three. It featured the Met’s first Mélisande, Pelléas, Arkel and conductor (Bori, Johnson, Rothier and Hasselmans), as well as Ezio Pinza as Golaud, a recording sadly lost to us. Fortunately, the following season’s broadcast of 7 April 1934 from the Met on tour in Boston exists complete and also features Bori, Johnson, Pinza, Rothier and Hasselmans, but, as would be expected, is in very poor sound.

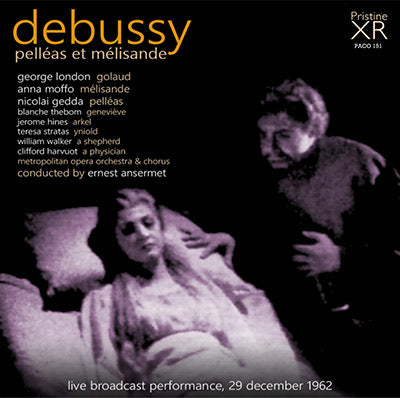

The timing of this release could not be more appropriate as we acknowledge the centenary of Debussy’s death. The 29 December 1962 broadcast presented here was only the sixth broadcast of the opera and features an equally illustrious cast in the presence of Anna Moffo, Nicolai Gedda, George London, Jerome Hines, Blanche Thebom and a young Teresa Stratas who would herself become one of the great Mélisande’s of our generation. In the pit was the eminent Swiss maestro, Ernest Ansermet, in what was to be his only season at the Met and this, in fact, is his last performance with the company and his only Met broadcast. This broadcast also provides us with the only opportunity to hear Moffo and Gedda as the protagonists and Thebom as Geneviève. The next time we hear Stratas in the opera it will be as Mélisande. Another interesting aspect of this broadcast is that Ansermet opens a small cut in Act Four thereby allowing us to hear for the first time on a broadcast of the opera a short scene for Yniold. After this broadcast, it would be a little over nine years before the radio audience would hear the opera again.

This release also includes two very special bonus features. Prior to the start of the performance, Ernest Ansermet spoke briefly to the radio audience about the musical aspects of the opera. Then during the first intermission, Opera News on the Air presented an in-depth interview with our Maestro hosted by Edward Downes.

In the New York Times review published on 1 December 1962 of the first performance of the run (which featured Theodor Uppman as Pelléas; Gedda would take over at the third of the five performances that season), Harold C. Schoenberg concluded his review with these words: On the whole, then, a fine performance of the exquisite, gossamer tonal world that makes up “Pelléas et Mélisande.” With Mr. Ansermet holding it together with such suppleness, and with so reliable a cast, the opera could not help but make an impact. “Impact” might not be the right word, “Pelléas et Mélisande” being the crepuscular thing it is, but for several hours last night at the Metropolitan Opera was the realm of a magic, subdued, dim-lit empire.

Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande is based on Maurice Maeterlinck’s play of the same name. Debussy himself set the text to music. The work revolves around the mysterious young Mélisande, who Golaud finds lost in a forest while hunting. She reveals only her name to him but nothing of her origins. Six months pass and we learn that Mélisande and Golaud have married. They eventually return to the castle of his grandfather, the aged King Arkel of Allemonde. Here Mélisande meets Golaud’s younger half-brother, Pelléas. They become increasing attached to each other, arousing Golaud’s jealousy. He tells Pelléas that Mélisande is pregnant and that he should avoid contact with her. But as Golaud’s suspicions between the two deepens, he begins to go to extreme lengths to discover the extent of the relationship between them. He forces his own son from a previous marriage, Yniold, to spy on the couple and even goes so far as to become physically violent with Mélisande. Pelléas tells Mélisande that he has decided to leave the castle but they arrange a final meeting where they confess their love for each other. Golaud, who has been spying on them, rushes forward and kills his half-brother. Mélisande lies ill in bed having given birth to a daughter. Alone with her, Golaud presses her to confess her love for Pelléas, but she maintains her innocence to his dismay. Arkel brings the meeting to an end as Mélisande quietly dies. Arkel tells the distraught Golaud that it is now the child’s turn to live.

Anna Moffo (27 June 1932 - 9 March 2006), our Mélisande, was born in Wayne, Pennsylvania. Turning down an offer to go to Hollywood, Moffo studied at the Curtis School of Music in Philadelphia. After winning a Fulbright Scholarship in 1954, she travelled to Italy to study and quickly established herself through appearances on RAI Television. She returned to the United States and made her American debut at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1957. She made her Met debut on 14 November 1959 in what was her most famous role, Violetta in La Traviata, which she sang 80 times during her Met career. Her full lyric soprano voice and easy vocal agility allowed her to encompass a wide variety of 21 different roles during her 17 years with the company. She returned to the Met for one final appearance at the Centennial Gala in 1983. These were her only performances of Mélisande at the Met.

Our Pelléas, Swedish tenor Nicolai Gedda (11 July 1925 - 8 January 2017), was one of the most versatile tenors of our generation. His superlative linguistic abilities allowed him to sing in at least seven different languages. In addition to his beautiful, evenly produced voice, with its easy upper extension, he possessed flawless legato and diction. With a career spanning over an astonishing 50 years, Gedda sang 367 performances of 28 operas during his 25 seasons at the Met, including the World Premiere of Barber’s Vanessa in 1958 and the United States Premiere of Menotti’s The Last Savage in 1964. In 1972, he sang Gherman in the first-ever Met performances of The Queen of Spades in its original language, the first time a Russian opera was performed in the vernacular. His repertory ranged from the classical operas of Gluck and Mozart to the bel canto works of Donizetti and Bellini, as well as Verdi, Puccini, Strauss (Johann and Richard) and Smetana and he excelled in the French repertory of Gounod, Bizet, Offenbach, Massenet and Debussy, as we can hear on this broadcast. Like Anna Moffo, these were his only performances of the opera at the Met.

Golaud is portrayed by the great singing actor bass-baritone George London (30 May 1920 - 24 March 1985). Born in Montréal, Canada, London was only 25 when called upon by conductor Antal Doráti to make his professional debut. Within a few years he was engaged by the Vienna State Opera and his career was established. Famous for his Wagnerian roles, he was chosen to sing Amfortas in the first post-war production of Parsifal at the Bayreuth Festival in 1951. Later that year, on 13 November, he made his Metropolitan Opera debut as Amonasro in a New Production of Aïda on Opening Night of the 1951-52 Season. One of the highlights of his career was the honor of becoming the first North American artist to sing the title role of Boris Godunov at the Bolshoi Opera during the Cold War in 1960. Despite being diagnosed with a paralyzed vocal cord in the early 1960s that brought his career to an early end, London still performed over 250 times in 18 different operas during his 15 seasons with the Met. During this time, he sang in two United States premieres, Arabella in 1955 and The Last Savage in 1964.

Pennsylvania born Mezzo-Soprano Blanche Thebom, our Geneviève, (19 September 1915 - 23 March 2010) is perhaps best remembered for performance of Brangäne in the now-historic first complete studio recording of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde staring Kirsten Flagstad and conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler released by EMI in 1952 (PACO067). It was also the role of her Metropolitan Opera debut on 28 November 1944. While particularly well-known for her roles in the Wagnerian repertory (Tristan und Isolde, Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Götterdämmerung, Tannhäuser, Lohengrin and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg) it was the role of Amneris in Aïda (her 1953 Met broadcast of the opera is available on PACO147), which she performed 80 times between 1946 and 1959, that she would sing more than any other during her 23-year Met career. She took part in two Met premieres, The Rake’s Progress in 1953 and Arabella in 1955. Her final performance at the Met was as the Countess in The Queen of Spades during the first season at the New Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center in 1967.

Our Yniold, Canadian soprano Teresa Stratas (born 26 May 1938), was only 21 years old when she made her Met debut on 28 October 1959 as Pousette in Manon after winning the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions earlier that year. Her Met career spanned 35 years during which time she performed 385 times in 39 roles in 35 operas. Like her colleagues on this broadcast, Nicolai Gedda and George London, she also sang in the United States Premiere of The Last Savage in 1964 as well as performing the title role in what was arguably her greatest triumph, Lulu, in the Met Premiere of the complete three act version of the opera. Known for her intensely dramatic portrayals of some of the most complex operatic characters, she created the role of Marie Antoinette in the World Premiere of John Corigliano’s The Ghosts of Versailles in 1991. As luck would have it, her final Met performance was a broadcast in which she sang Jenny in Kurt Weill’s The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny on 9 December 1995.

As impressive as all of the above statistics are, it is our Arkel, California-born bass Jerome Hines (8 November 1921 - 4 February 2003), who boasts the record number of performances among his colleagues in this broadcast: 869 performances in 45 roles in 39 operas over the course of his 41 seasons with the Met. His debut took place on 21 November 1946 as The Officer in Boris Godunov, an opera that he would perform no less than three different roles in during his career at the Met. He added Pimen in 1953 and the title role in 1954, becoming the first US-born singer to perform the role with the company. He performed in three Met premieres (Peter Grimes in 1948, Khovanshchina in 1950 and Macbeth in 1959) and was chosen to sing the role of the Grand Inquisitor in Don Carlo for the Opening Night of Rudolf Bing’s first season as General Manager of the Met in 1950. He performed the role of Arkel 22 times during his Met career between 1953 and 1983. His final performance was as Sparafucile in Rigoletto on 24 January 1987. A deeply religious man, he composed an opera based on the life of Jesus entitled I Am the Way, which premiered in New York City in 1956, with Hines himself in the title role.

Conductor Ernest Ansermet (11 November 1883 - 20 February 1969), was born in Vevey, Switzerland. Originally a Mathematics Professor at the University of Lausanne, Ansermet changed career paths and began conducting professionally in 1912. It was while taking time from his teaching duties and traveling to Paris in 1905 that he first heard Pelléas et Mélisande. He met Debussy for the first time in 1910 and became a champion of his works. Between 1915 and 1923, while touring in France with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, he founded the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. The orchestra would rise to prominence after the Second World War when it signed a long-term contract with Decca Records, with which he would record Pelléas et Mélisande twice, in 1951 and again in 1964, this time in stereo. Ansermet had just turned 79-years old at the time of this Met broadcast and came to it with a lifetime of understanding of the works of Debussy. While he also conducted two performances of Manuel de Falla’s El amor brujo and Atl ántida with the forces of the Metropolitan Opera for the inaugural week of celebrations of Lincoln Center in Philharmonic Hall (as it was then known), five performances of Pelléas et Mélisande would prove to be the only time he would conduct at the Met.

Notes by Michael Scarola

DEBUSSY Pelléas et Mélisande

Anna Moffo - Mélisande

Nicolai Gedda - Pelléas

Blanche Thebom - Geneviève

Jerome Hines - Arkel

Teresa Stratas - Yniold

William Walker - A Shepherd

Clifford Harvuot - A Physician

Metropolitan Opera Orchestra & Chorus

conducted by Ernest Ansermet

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Anna Moffo and George London as Mélisande and Golaud

Broadcast live from the Metropolitan Opera House, New York on 29 December 1962

Additional 15 minute Ansermet interview included with downloads

Total duration: 2hr 37:06

(2hr 52:21 with interview)

Ernest Ansermet Leads Opera in His Debut

By HAROLD C. SCHONBERG

DEBUSSY’S “Pelléas et Mélisande” is a permanent hanger-on: never fully in the repertory, never wholly apart from it. There always is a hard core that thinks it quite the most wonderful opera of this century, and among that core are many professionals and sensitive music-lovers. The public, though, has never taken “Pelléas et Mélisande” to its heart, just as it never has adopted Verdi’s “Falstaff.” Both operas lack the grand gesture, and are considered, in certain quarters, hopeless—without arias, without melody.

The Metropolitan Opera has not done ‘‘Pelléas et Mésande” since the 1959-60 season. Last night it returned, with several new singers and a new conductor. The distinguished Ernest Ansermet made his debut in this work. He had conducted Falla’s “Atlantida” during the open-week ceremonies at Philharmonic Hall, using Metropolitan Opera forces; but last night will go on the books as his official debut.

Naturally he was the hero of the evening. ‘‘Pelléas et Mélisande” is a conductor’s opera, and it demands the services of a man who is a precise stylist and a precise technician. Despite its seeming economy of means, “Pelléas et Mélisande” is very difficult to conduct. Textures must be transparent; the score is a cobweb of sound, seldom arising above a mezzoforte. At that, Mr. Ansermet released his forces more than do most conductors, and the opera last night seemed to have a little more red blood in it than usual.

Part of this was also due to George London, who was heard in the role of Golaud (not a new assignment for him). There is nothing unfettered about his characterization, and in the first scene of the fourth act he almost gave the impression he was singing Boris Godunov. He did let himself go too much here. Elsewhere his impersonation was tortured and intense, as it should be.

Anna Moffo was the Mélisande, singing the role for the first time at the house. She has the physical characteristics for the role. At present, though, her interpretation is concerned primarily with externals. Her gestures are a little too studied, and her conception lacks the air of mystery so needed to make Mélisande interesting. Vocally Miss Moffo sang accurately, though with a rather hard emission of tone. She never has been a colorist; her strength lies in a straightforward and literal translation of the notes.

Theodor Uppman sang the role of Pelléas, as he had done the last time the opera was around. He is an intelligent singer, and a competent actor. Thus Pelléas was heard under good auspices, and so was the role of Geneviève, sung for the first time by Blanche Thebom. Jerome Hines repeated his characterization of King Arkel, singing as beautifully as ever.

New to the cast was Teresa Stratas. She undertook the role of Yniold. Physically and vocally it was a perfect match. Miss Stratas is a diminutive girl, and thus it caused no wrench to the imagination when she appeared as a little boy. She sang her phrases in a piping manner, and acted like a child without being obnoxious about it.

On the whole, then, a fine performance of the exquisite, gossamer tonal world that makes up “Pelléas et Mélisande.” With Mr. Ansermet holding it together with such suppleness, and with so reliable a cast, the opera could not help but make an impact. “Impact” might not be the right word, “Pelléas et Mélisande” being the crepuscular thing it is, but for several hours last night the Metropolitan Opera was the realm of a magic, subdued, dim-lit empire.

The New York Times

December 1, 1962