This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

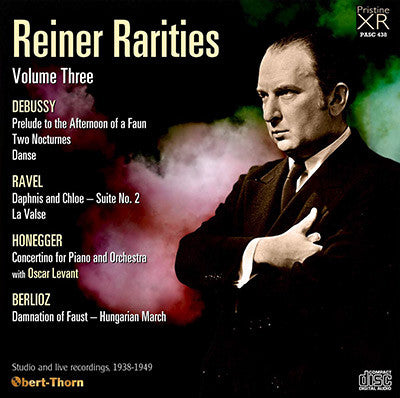

Reiner Rarities, Volume 3: Debussy, Ravel, Honegger and Berlioz

"This is a CD that will haunt your imagination long after you’ve heard it"- Fanfare

Like the two earlier releases in this series (PASC 235 and 294), this volume of Reiner Rarities features works which are rare in more than one sense First, these are Fritz Reiner’s only commercial recordings of the works presented. In addition, none of them have ever received an “official” CD reissue from their originating labels. The current release features all of Reiner’s French repertoire recordings which fall under these criteria.

The Debussy Faune and Nocturnes come from Reiner’s

earliest issued recording session, although they were originally

published without crediting the conductor or the orchestra. They were

part of the “World’s Greatest Music” series recorded by RCA Victor for

the New York Post, which featured similarly anonymous recordings by Ormandy and the Philadelphia and Rodzinski and the NBC Symphony.

This session featured 78 players from Barbirolli’s New York Philharmonic, and also included works by Wagner. What is particularly striking here, as in many of the recordings featured in this program, is Reiner’s pacing, allowing the music to unfold with seeming inevitability even as he moves it along, choosing tempi that seem ideal. (The uncredited flute soloist in Faune is most likely John Amans, the Philharmonic’s principal at the time.)

The broadcast of the Daphnis Suite, although not a commercial recording, was part of the series of V-Discs released by the U.S. government for the entertainment of servicemen during World War II, and falls under Reiner’s issued discography. Again, one is struck by the pacing, the judgment in the length of pauses, and the choices for when (and how much) to use string portamenti to underline emotional points.

The Pittsburgh recordings document Reiner’s decade as music director of that city’s orchestra. In La Valse, Reiner does not play his hand too early, letting loose only in the final pages (in contrast to Munch, who, for all his admitted excitement, plays it at fever pitch from the start). The Ravel orchestration of Debussy’s Danse gets an appropriately energetic performance, while the rousing Berlioz march ends with an unusual, rarely-heard diminuendo.

In 1927, Reiner conducted the U.S. première of Honegger’s 1924 single-movement Concertino, a work which seems to have been somewhat influenced by Prokofiev’s Third Concerto. The soloist, Oscar Levant, is perhaps best known today for his acting work in such films as An American in Paris, The Band Wagon and Humoresque; but in his time, he was a highly popular piano soloist specializing in twentieth century repertoire (particularly the works of his friend, George Gershwin), as well as an author, composer and raconteur.

The sources for the recordings were American Columbia LPs for La Valse and the Honegger, and shellac 78 rpm discs for the remaining items, except for the Daphnis Suite, which was taken from a tape of original off-the-air acetates, which sounded better than the V-Disc dubbings.

Mark Obert-Thorn

DEBUSSY

1 Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune

Recorded 22 November 1938 in Carnegie Hall, New York

Matrix nos.: CS-028849-1/028850-1 - First issued on World’s Greatest Music SR-17

Nocturnes

2 Nuages

3 Fêtes

Recorded 22 November 1938 in Carnegie Hall, New York

Matrix nos.: CS-028851-1/028852-1A/028853-1A/028854-1A - First issued on World’s Greatest Music SR-18/19

4 Danse (Tarantelle styrienne) (orch. Ravel)

Recorded 1 April 1947 in the Syria Mosque, Pittsburgh

Matrix nos.: XCO-37578 - First issued as Columbia 12785-D in album X-296

RAVEL

Daphnis et Chloé – Suite No. 2

5 Lever du jour

6 Pantomime

7 Danse générale

Live broadcast 2 September 1945 from the CBS Studios, New York

Matrix nos.: VP-1543-D5-TC-1340-1H/VP-1544-D5-TC-1341-1M/VP-1545-D5-TC-1342-1D

First issued as V-Disc 546/7

8 La Valse

Recorded 1 April 1947 in the Syria Mosque, Pittsburgh

Matrix nos.: XCO-37575/7 - First issued as Columbia 12784-D/12785-D in album X-296

HONEGGER

Concertino for Piano and Orchestra

9 Allegro molto moderato –

10 Larghetto sostenuto –

11 Allegro

Oscar Levant (piano)

Recorded 6 July 1949 in the Columbia 30th Street Studios, New York

Matrix no.: XCO-41374/6 - First issued as Columbia ML 2156

BERLIOZ

12 Hungarian March (from La damnation de Faust, Op. 24)

Recorded 15 November 1941 in the Syria Mosque, Pittsburgh

Matrix nos.: XCO-31902 - First issued as Columbia 11709-D in album M-491

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York (Tracks 1 – 3)

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (Track 4, 8 & 12)

CBS Symphony Orchestra (Tracks 5 – 7)

Columbia Symphony Orchestra (Tracks 9 – 11)

Fritz Reiner, conductor

Fanfare Reviews

Reiner demonstrates his ability to take a score and realize it with such freshness and subtlety that it seems reinvented

Presenting Fritz Reiner conducting a program of French music may seem unexpected. We don’t usually associate him with this repertory. But as a Hungarian, Reiner came from a country heavily affected by French culture. He studied piano with Bartók, who was deeply influenced by Debussy. Reiner was a Modernist, drawn to the music of his lifetime. Also, as a brilliant orchestral technician, Reiner liked to present scores that challenged his abilities, such as those of Debussy, Ravel, and Arthur Honegger (who was Swiss). He recorded Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun and first two Nocturnes with members of the New York Philharmonic. The Prelude has qualities familiar from Reiner’s Chicago La mer, namely plasticity, gorgeous tone, and a delicate emphasis on musical transitions. My favorite stereo account of the Prelude is by Erich Leinsdorf and the Los Angeles Philharmonic on Sheffield Lab. It leaves you breathless, while Reiner’s is a more epicurean affair, portraying the faun’s dreaming as in Mallarmé’s poem. The first Nocturne, “Nuages,” comes off like a night scene by Whistler, with infinite variations of blue and gray. Reiner’s “Fêtes” is quick and lively, even a little fierce. My favorite stereo version of the complete Nocturnes, by Ernest Ansermet, presents an old-fashioned French orchestral sound that is probably closer to what Debussy would have expected than Reiner’s well-manicured performance. Interestingly, the same recording company in the same venue and year recorded John Barbirolli, the Philharmonic’s music director, in Debussy’s Ibéria. That rendition is very good, but lacks Reiner’s mastery.

For the Pittsburgh version of Debussy’s Danse in Ravel’s orchestration, Reiner demonstrates his ability to take a score and realize it with such freshness and subtlety that it seems reinvented. He conducted the CBS Symphony a number of times. In their broadcast of the second Daphnis and Chloé suite, the scenes are painted so vividly that they recall Marc Chagall’s illustrations for the story. Reiner’s tempos are flexible, with hints of portamento here and there. The unnamed first flute perhaps gives the performance of his life. Reiner gets a wonderful pagan feeling in the concluding “Danse générale.” His Pittsburgh La valse is the best recording of the work I’ve ever heard, challenging my memory of Jean Martinon conducting it in concert in the 1970s, with the Hague Philharmonic. In the opening, the strains of the waltz seem to come together out of some primordial time. The ensuing bite of the trumpets is amazing and frightening—there’s no oompah to this waltz. The composer Robert Bonnotto told me that the work should end with a feeling of menace. Reiner agrees. These Ravel recordings may lead you to hunt down Reiner’s excellent 1952 NBC Le tombeau de Couperin, in his Great Conductors of the 20th Century set.

My first acquaintance with Honegger’s Concertino for Piano and Orchestra was a lyrical performance on a Turnabout LP by Walter Klien and Heinrich Hollreiser. Reiner conducted the American premiere in 1927. Here he leads a chamber orchestra dubbed the Columbia Symphony. He and the pianist Oscar Levant were friends; there are some interesting anecdotes about Reiner in Levant’s first book, A Smattering of Ignorance. He and Reiner find a mixture of Bach and 1920s Paris in the Concertino. Levant’s tone is distinctive, broad but delectable in its details. Reiner’s accompaniment is hand in glove, with an appealing insouciance. The Pittsburgh “Rákóczy March” is as much Hungarian as French, with some rhythms that sound like Liszt. The concluding diminuendo is an interesting, unexpected touch. Producer Mark Obert-Thorn’s remasterings always are pleasant to listen to, and, in the case of La valse, a good deal more so. Indeed, it’s amazing how well the 1938 recordings of the New York Philharmonic capture the beauty of its tone, something Levant felt emanated from the concertmaster, Michel Piastro. This is a CD that will haunt your imagination long after you’ve heard it. Reiner’s French repertoire may not have been extensive, but the works he did perform he clearly savored.

Dave Saemann

This article originally appeared in Issue 39:1 (Sept/Oct 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.

“There are few conductors who impress an orchestra (also composers) at first contact as strongly as does Fritz Reiner, whose knowledge of everything pertaining to the mechanical performance of music is, briefly, unparalleled. He has evolved a personal sign language which leads an orchestra through the most complex scores of Strauss and Stravinsky with the ease and sureness of a tightrope walker who performs a backward somersault blindfolded. Whenever the complexity of the scoring is a sufficient challenge to his skill, Reiner will subdivide beats, flash successive cues to remote sections of the orchestra with either hand and meanwhile indicate the pianissimo, in which he takes such great delight, by a bodily movement that totals by a kind of physical mathematics to the exact effect on the printed page. His ear so acute, not only for intonation but also for dynamics, that he can detect a wrong bowing when his back is turned to the section from which it emanates.

“Together with these faculties is a facility for terrifying inferior orchestras unequaled among conductors of the present day. His technique in this field is no less sophisticated than it is in his conducting. A mere series of facial expressions can shade his degrees of contempt for a nervous oboist or a fright-palsied violinist as artfully as he fades an orchestra from mezzo piano to pianissimo. His passion for the least audible of sounds has created among violinists a new form of occupational illness known as ‘Reiner-paralysis.’ When he is sufficiently challenged by an operatic score, such as Der Rosenkavalier, or by the collaboration with a fine soloist, he can achieve fabulous results. The reactions he induces from the orchestras he has conducted run the full gamut of all emotions but deep affection.”

That was Oscar Levant on the subject of Fritz Reiner in his book A Smattering of Ignorance, written in 1939. Ten years later, he found himself receiving the benefit of Reiner’s superior conducting technique when they collaborated on a recording of Honegger’s 1924 Concertino for Piano and Orchestra, Originally coupled on a 10-inch LP with Eugene Ormandy’s successful (and poker-faced) attempt to squeeze The Sorcerer’s Apprentice onto one 78-rpm disc, it has probably never been issued on CD until now. I have heard two other recordings of the Honegger. Thibaudet and Dutoit toss it off like a piece of 1920s “wrong-note” fluff, which I suppose it is. Weber and Fricsay seem wittier and more tongue-in-cheek in a nice performance that now comes only as part of a 45-disc set devoted to Ferenc Fricsay’s DG recordings. The approach of Levant and Reiner, however well-executed, is more sober and serious and I don’t think this necessarily works to the music’s advantage. Oscar Levant humorless?

The rest of the CD certainly demonstrates the superior baton technique Levant was praising. In the “Rákóczy March” from La damnation de Faust, Reiner is the supreme drillmaster, securing brilliant, precise playing from the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. The performance, oddly, ends with a diminuendo—is that the way it ends in La damnation? In the Debussy Nocturnes and Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, he demonstrates that the best way to deal with “Impressionism” isn’t necessarily to create a sonic fog but to pace it flexibly, reacting to the music’s “inner rhythm” as he perceives it and exposing detail. Reiner’s Faune and “Nuages” are models of rhythmic suppleness and exposure of orchestral color even with their 1938 sound, and the New York Philharmonic, which wasn’t always polite to guest conductors, plays for him. The performers were uncredited. The 78s were issued as part of a budget series called The World’s Greatest Music, which also included anonymous recordings by Ormandy and Rodzinski. Some may find the procession in Fêtes a bit too sprightly—he also zips through Ravel’s orchestration of Debussy’s Danse, probably to get it on one 78-rpm side

Regrettably, other than La mer and Iberia, Reiner’s opportunities to record Debussy’s works with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra were limited, presumably because Charles Munch was French. It is likely that the latter also received priority from RCA Victor where Ravel’s music was concerned, although Reiner did manage to record the Rapsodie espagnole, which Munch also recorded with the Boston Symphony; the Valses nobles et sentimentales, which Munch later recorded with the Philadelphia Orchestra for Columbia; and Alborada del gracioso, which Munch did not record. Dating from 1947, Reiner’s Pittsburgh La valse is an aggressive, brilliant rendition that was probably the best recording/performance of its time. Too bad he never got to record it again 10 years later. The Daphnis Suite is marred by narrow dynamic range and some congestion at loud volumes. I think the lower strings are barely audible at the start of the big climax in “Daybreak”; at the climax, Reiner holds the brasses down just enough for the violins to shine through. One might expect the “Danse générale” to be exhilarating—the real surprise is the “Pantomime,” with its pauses for breath, so leisurely and flexible, which Reiner could almost be said to milk. It’s almost hypnotic in its effect (at least on me). The performances give pleasure—but also frustration, when one considers what might have been had he had the opportunity to take advantage of post 78-rpm/monaural recording technique.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 39:1 (Sept/Oct 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.