This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

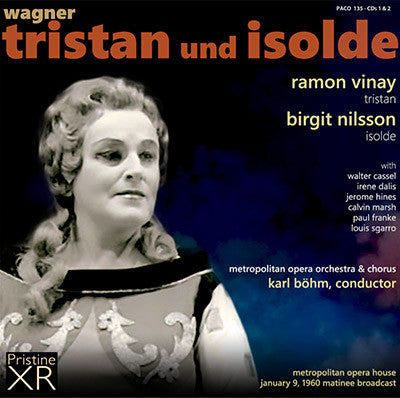

- Cover Art

- NY Times Articles

Birgit Nilsson's Isolde brings the house down in her New York debut

Karl Böhm conducts his only broadcast Met Opera Tristan und Isolde in 1960 to rapturous response

“with a voice of extraordinary size, suppleness and brilliance,

she dominated the stage and the performance”

NEW YORK TIMES

This stunning performance of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde was broadcast live from the Metropolitan Opera just three weeks after Birgit Nilsson's astonishing debut in the role of Isolde in New York made front page news and produced reams of adoring copy. It marks her first matinee broadcast as well as the only time Böhm, whose 1966 Bayreuth Tristan und Isolde is widely regarded as among the very best, broadcast the opera from the Met.

Working from two high quality sources, this XR remastering brings us the full glory of this remarkable debut in superb Ambient Stereo sound. Announcements from Milton Cross at the start and finish of each act (one act per CD) add to the sense of grand occasion as does the rapturous applause of the Metropolitan Opera audience.

.Andrew Rose

-

WAGNER Tristan und Isolde, WWV90

Live matinee performance

Metropolitan Opera New York, 9 January1960

Broadcast on NBC Radio

CASTTristan - Ramón Vinay

Isolde - Birgit Nilsson

Kurwenal - Walter Cassel

Brangäne - Irene Dalis

King Marke - Jerome Hines

Melot - Calvin Marsh

Sailor's Voice - Charles Anthony

Shepherd - Paul Franke

Steersman - Louis Sgarro

Orchestra & Chorus of the Metropolitan Opera

Karl Böhm, conductor

Birgit Nilsson as Isolde Flashes

Like New Star in ‘Met’ Heavens

Swedish Soprano’s Voice in Debut Is

Compared With Kirsten Flagstad’s Best

by HOWARD TAUBMAN

New York Times, 19 December 1959

In

her New York debut the Swedish soprano assumed one of the most

demanding roles in the repertory and charged it with power and

exaltation. With a voice of extraordinary size, suppleness and

brilliance, she dominated the stage and the performance. Isolde's fury

and Isolde's passion were as consuming as cataclysms of nature.

Before

the first act was over a knowing audience at the Met's new production

of "Tristan und Isolde" was aware that a great star was flashing in the

operatic heavens. At the end of the act the crowd remained in their

seats, waiting for Miss Nilsson to take a solo bow. And when she came

out alone, they roared like the Stadium fans when Conerly throws a

winning touchdown pass.

It

was an audience that knew its Wagnerian manners. It did not break into

applause during the performance, but again at the end of the second act

it manifested its enthusiasm with sustained applause and cheers for the

newcomer.

At

the final curtain the audience began a thunderous demonstration. As the

principals came out for repeated bows all eyes were on the soprano. An

ovation was building up for her, and it broke out into a thunderous

shout as she came out alone.

People

seemed disinclined to go home. The lights in the theatre were dimmed,

but men and women throughout the house remained near their seats,

applauding for Miss Nilsson's return. After more than fifteen minutes of

plaudits, the enthusiasts let Miss Nilsson return to her dressing room.

Like

Miss Flagstad, who created a similar sensation in her 1935 debut, Miss

Nilsson relied first and foremost on the voice. Her soprano has

apparently limitless reserves of tone. In a range well over two octaves,

no note loses its quality, and high C's emerge with stunning impact.

Although

she is small and trim compared with the run of Wagnerian sopranos,

Miss. Nilsson can make her voice soar over the fortissimos of a large

orchestra in full cry as if it were jet-powered. Her singing is

beautifully focused, always in the center of the tone. Not so darkly

colored as Miss Flagstad's huge voice, Miss Nilsson's has a gleaming

refulgence. It can be whitish, to use the jargon of the vocal trade, but

it can glow with warmth.

Miss

Nilsson can do just what she wishes with this instrument. She can

subdue it to a wisp of tone and she can modulate phrases with subtlety.

She has a sure grip on the emotional curve of one of opera's most

challenging roles.

The

new soprano, who has sung extensively in Europe, including Bayreuth,

the Wagnerian shrine, as was as in San Francisco and Chicago, also knows

how to act. She moves with poise and dignity. She does not stress the

tenderness in Isolde, but even that element in the character comes

through in the voice.

Miss

Nilsson was born in Karup, grew up on a farm and studied music in

Stockholm. She made her debut as Lady Macbeth in Verdi's "Macbeth" at

the Royal Opera in Stockholm twelve years ago. From the Italian

repertory she moved into German, turning eventually to the imposing

Wagnerian roles, which her gifts as a dramatic soprano made almost

imperative. In a time of limited candidates for the most difficult roles

of the repertory, she stands as a dominant figure in the world of

opera.

Miss

Nilsson's arrival was bound to take precedence over all other elements

in this new "Tristan," but there were other values. Most impressive of

these was Karl Boehm's conducting.

His

is a vigorous, dramatic conception. He is painstaking in his regard for

instrumental textures and balances. One can hear subtleties in the pit

often obscured in routine readings. And how the Met orchestra played!

Rhythms are incisive. Some conductors favor more leisurely tempos, but

Mr. Boehm's choice of a vivid pulse has its merits.

One's

only reservation is that he holds the orchestra back just a shade at

the climaxes. With an Isolde like Miss Nilsson he can let the thrilling

Wagnerian waves of sound flood the theatre. This soprano will ride them

triumphantly.

Mr.

Boehm has restored some of the cuts usually made in "Tristan" at the

Met, particularly one in the Love Duet. With an incandescent performer

like Miss Nilsson this did not seem to lengthen a long, long opera at

all.

The

Tristan was Karl Liebl, a German tenor, who made an unimpressive debut

last season and who stepped in on this occasion for the indisposed Ramon

Vinay. Though he is no Heldentenor, Mr. Liebl did better than anyone

had a right to expect. He managed his light voice with reasonable

effectiveness. He has no magnetism as a performer, and his voice is not

built for a long pull, but he bravely carried out his assignment.

In

the first act duet the performance went well. In the Love Duet things

were not ideal. Here the performance was occasionally like a ship that

had lost its delicate equilibrium, riding proudly when Miss Nilsson sang

and listing a little when Mr. Liebl took over or joined her.

The

rest of the well-balanced cast was American. Irene Dalis was an

intelligent, sensitive Brangaene; her naturally rich voice was a little

hollow at times. Walter Cassel was a sturdy, affecting Kurvenal. Jerome

Hines was both regal and movingly human as King Marke. Charles Anthony

as the sailor, Paul Franke as Melot, and Louis Sgarro as the steersman

made much of small parts.

Herbert

Graf's staging had a notable and telling simplicity. Teo Otto's sets

with their dash of surrealism were fundamentally old hat; for

generations the Met has had a fatal tendency to opt for styles in design

long after they became passé. The new production was a gift of Mrs.

Elon Huntingon Hooker from her four daughters.

In

recent years Wagner's music-dramas have had few performances at the

Met. Cassandras declared that Wagner was finished. He is far from

finished. There is nothing wrong with him that a sovereign singer like

Miss Nilsson will not help to cure.

Star ready to tackle new role

after finishing the 'Liebestod'

by JOHN SIBLEY

New York Times, 19 December 1959

When Birgit Nilsson walked offstage at the Metropolian last night after her triumphant New York debut as Isolde, she announced coolly — but far from haughtily — “I could sing Turandot right now.”

“She’s not even winded,” a stagehand exclaimed, as the smiling Swedish soprano curtsied graciously and threw kisses to an ecstatic audience that greeted each curtain call appearance with thunderous “Bravos.”

Behind the curtain, as the cast clamored to congratulate ¡her, Miss Nilsson acknowledged their praise trilingually. “You’re so kind,” in English, “Danke, sehr erfreut,” in Wagner’s tongue. Then words of thanks to admirers from her native Sweden.

The indefatigable soprano trilled snatches from the opera while Tristan (Karl Liebl) and the others answered their curtain calls. She had lived up to the reputation gained in rehearsals — that of a star ready to begin all over again after singing the closing “Liebestod.”

In a dressing room overflowing with flowers, Miss Nilsson dropped some of her reserve. “That wonderful public,” she sighed. “They carried me.”

It was then that she said she was ready to sing “Turandot,” the Puccini opera she had just signed a contract to sing during the Met’s next season.

In a standard questionnaire sent by the Met to all its performers, Miss Nilsson had written that “Tristan und Isolde” and “Turandot” were her favorite operas. She had already played Isolde this year in five cities: in Lisbon, at La Scala in Milan, in Rome, Vienna and Bayreuth.

Was this her best performance of Isolde? She shrugged. “You’re never satisfied,” she said.

Then, as flashbulbs flickered, her husband, Bertil Niklasson, a Swedish businessman, was asked the same question. His reply: an excited, “Ja, Ja, Ja, Ja!”

Despite her aplomb, Miss Nilsson was coyly feminine when asked her age. “In Europe,” she smiled, “nobody asks a lady that.” Her answers to the Met questionnaire indicated she was in her early thirties. But in the space after “date of birth” she had written, “May 17.”

Fanfare Review

If I had to retain in my collection a single example of Birgit Nilsson’s Isolde, it would be this one ... Shattering

Do not look here for advice to save money on the grounds that you don’t need another Tristan recording. You do need this one if this opera and/or Wagnerian singing is something you care about.

There are, of course, many other options that have preserved great performances of the role of Isolde by Birgit Nilsson, including DG’s classic Böhm-led 1966 Bayreuth recording with Windgassen. There are some important performances of the opera with Nilsson and Jon Vickers, the finest Tristan she ever sang with, but they are all seriously flawed in many ways, sound quality and/or conducting among them. As great as the DG set is, I have always found Windgassen less than an ideal Tristan, though William Youngren liked him very much in his Fanfare review of that release (11:6). It seems to me that Ramon Vinay brings a vocal weight and richness of timbre that is a better match for both the music and Nilsson’s sound.

It is Nilsson, first and foremost, that makes this essential listening. The Swedish soprano’s Met debut occurred three weeks earlier, in this same role. The critics and public anointed her a superstar by the final curtain of that debut, and this recording demonstrates the justification for the anointment. Hearing her at her very freshest (she was 41 at the time), with a voice that balanced perfectly the elements of tonal beauty and brilliance, is a truly thrilling experience. I happened to attend this performance, as a standee, and it remains among the handful of greatest operatic experiences in my memory (the Nilsson/Corelli Turandot performances are in that category, along with Otello evenings spent with del Monaco, Tebaldi and Warren). It was wonderful to listen to these discs and learn that my memory had not played tricks on me—it truly was something extraordinary.

Earlier in the run of this production (December 28) the Met experienced an evening that has gone down in its history: three indisposed tenors, each of whom agreed to sing one act opposite Nilsson (Vinay, Karl Liebl, and Albert da Costa is the answer to that trivia question, and in that order). Here Vinay shows no signs of the illness that forced him to limit himself to only act I two weeks earlier. One cannot pretend that Vinay sounds young and fresh; after all he had been singing at the Met since 1946 and was a year away from finishing his career there. But there is a foundation of richness to the timbre, and it is married to a true understanding of how Wagner’s music goes and a genuine dramatic instinct that make this a very satisfying performance. He is spectacular in his big third act delirium scene, with an intensity that will leave you breathless. He and Böhm partner perfectly in this scene.

Irene Dalis was the Met’s reigning Brangäne in her two decades with the company, and we can tell why from this performance. Particularly in the first act she creates a sympathetic, human Brangäne, not merely a foil for Nilsson’s overwhelming Isolde, and she produces a lovely, opulent sound. Hines also produces a big, even sound, but he doesn’t break your heart the way the best King Markes do (e.g., Kipnis, Salminen, and Pape). Cassel’s Kurwenal lacks any subtlety, though it is decently sung. The remaining roles are taken more than adequately, perhaps less than superlatively except for Charles Anthony’s beautifully sung Sailor.

What helps to make this performance unforgettable is the conducting of Karl Böhm. To my ears Böhm was an uneven conductor, sometimes inspired, sometimes no more than competent. Even hearing different performances of this opera under his baton, one experiences that range of quality. No doubt some will find him a bit rushed here—and indeed his tempos are frequently quicker than even his own other documented performances. But there is also a flexibility in evidence, a willingness to caress the line and really shape the music, that he does not always display.

Pristine has done its usual amazing work on the restoration. In the ambient stereo version that I listened to, the sound is natural, surprisingly open and with a realistic perspective between voice and orchestra. At climaxes one experiences a bit of cramping, but overall there is no sonic impediment to full enjoyment of the music. Pristine has removed some extraneous audience noises, but couldn’t get all the coughing out.

If I had to retain in my collection a single example of Birgit Nilsson’s Isolde, it would be this one, because of the astounding vocal freshness she demonstrates, the individual contributions of Vinay, Dalis, and Böhm, and the total impact of the entire performance. Shattering.

Henry Fogel

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:3 (Jan/Feb 2017) of Fanfare Magazine.