This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

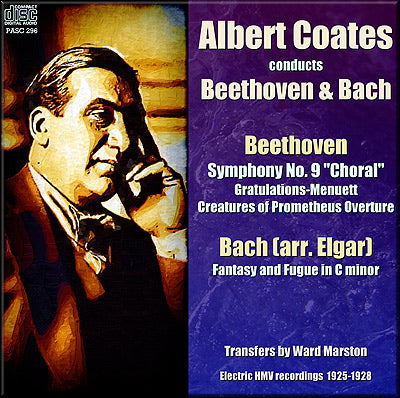

- Cover Art

Albert Coates - one of the great pioneering British conductors

Beginning our Coates season from Ward Marston

Introduction to our Albert Coates series:

About five years ago I travelled to the UK for a couple of days in order to meet up with the then editor of Gramophone (and now editor-in-chief), James Jolly. The main subjects of discussion were proposals for the Gramophone website and the possibility of a tie-in with the National Gramophonic Society recordings, a good number of which Gramophone had in storage with EMI.

At the end of our long lunch, with various ideas talked through, our discussion started to range a little wider, and James touched on a name he was really keen to hear more of: Albert Coates. I must admit that at the time I had very little awareness of Coates, but some research revealed him to be one of the greatest and most forward-looking British conductors of his day, a leading Wagnerian, and perhaps as a result of being Russian-born (to an English father), someone with a strong affinity to Russian music.

In 1919 he was appointed chief conductor to the London Symphony Orchestra, and began to make recordings with them for the Columbia Record Company in London. However, a decision by Coates to switch allegiances to HMV a couple of years later led to a number of recordings coming out during the 1920s listing him as conductor of an anonymous orchestra - which was almost certainly comprised largely of "moonlighting" members of the LSO.

Thus his electrical recording of Beethoven's 9th, one of, if not the first microphone recording of the symphony, appeared in 1926 without proper credit, and is still excluded from the main body of the LSO's official discography - and we thus cannot be 100% sure of the precise make-up of the orchestra that does play, though it is listed in an appendix as being the LSO. By 1927 HMV had bagged the LSO and normal service was resumed for a while, though his contract with the orchestra had expired in 1922 and from then on he had no permanent conducting post. He relocated to the US during World War II and thereafter to South Africa, where he died in 1953.

Although Coates continued to record on and off until 1945, it might be well-argued that his major contributions to the recorded canon took place during the 1920s, and it is this period which we're concentrating on in a major series put together by Ward Marston, versions of some of which may have been circulating amongst collectors, but which is seeing its first formal, commercial issue here on Pristine.

The series will bring together both electrical and acoustic recordings and is initially running to 6 volumes, with a possible further three later this year or in 2012.

Andrew Rose, from Pristine Newsletter, 8th July 2011

NB. The present recording of Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 has a significant cut partway into the third movement, similar or possibly identical to a cut Coates used in his earlier, acoustic recording of the symphony. The work is otherwise complete and uncut.

-

BACH (arr Elgar) - Fantasia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 537

Recorded 11 and 12 October 1928

Issued on HMV D1560

-

*BEETHOVEN - Gratulations-Menuett, WoO 3

Recorded 22 October 1925

Issued on Victor 9048

-

BEETHOVEN The Creatures of Prometheus - Overture , Op. 43

Recorded 6 January 1927

Issued on HMV D1163

-

*BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 "CHORAL"

Recorded 14, 15 and 19 October 1926

Transferred from Z shellac Victor pressings 9061-68 (except final disc, from a Victor Orthographic pressing)

Elsie Suddaby, soprano

Nellie Walker, contralto

Walter Widdop, tenor

Stuart Robinson, bass

Philharmonic Choir (dir. Charles Kennedy Scott)

London Symphony Orchestra

Albert Coates, conductor

(*Credited to Symphony Orchestra, probably members of LSO)

Transfers by Ward Marston

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Albert Coates

Special thanks to Richard Kaplan for supply of original 78s used in this transfer

Total duration: 78:04

MusicWeb International Review

Ward Marston has done a fine job with the Victors for the Ninth

The mighty Choral symphony, rather like Mahler symphonies,

offered quite a challenge to the youthful recording studios.

And yet even the acoustic horn didn’t shy away from the challenge.

In Berlin, in 1923 and on 14 shellac sides, Bruno Seidler-Winkler,

recording pioneer, directed the forces of the Neues Symphonie-Orchester

in pursuit of his goal. Even earlier, in 1921 - though the task

was not completed until 1924 – Frieder Weissmann led the Blüthner-Orchester,

Berlin, in the Ninth, though in one of those twists beloved

by 78 lovers, duties for the finale were taken over by the German

Opera House Orchestra and chorus under a completely different

conductor, Eduard Mörike. Even more delightfully, and confusingly,

two completely different sets of takes were issued, representing

different recordings made over the years by these forces. In

between all this, Anglo-Russian volcano Albert Coates nipped

into his London studios to set down his own recording with the

Symphony Orchestra, a bashfully anonymous band who were probably

the LSO.

Three years later he was back, with the same band, but this

time the studio recording was electric, working via microphone,

not the recording horn. The results remained formidable and

dynamic, hugely involving and intensely rousing. His dynamic

accelerandi, the speed of a greyhound out of the traps, animate

the second movement and reveal graphically his seismic approach.

It is never grammatically misplaced however, indeed it generates

a similar kind of focused energy as Toscanini was later to do

on disc in his cycles – and Coates is by no means slower than

the Italian. The slow movement sports a few well disguised disc

thumps – it’s vital, fluid and forward-moving, and not unmoving

in its way, especially since Coates is capable of vesting the

music with a vocalised cantilever that never fails to impress.

There’s a bit of a cut in the third movement. The finale is

launched with predictable vehemence – an intensity that prepares

one for the riches to come. The vocal quartet is fine; Walter

Widdop, that sterling Handelian and Heldentenor is at his penetrating

best; Elsie Suddaby deploys her crystalline purity to considerable

effect. The two lesser known names are those of contralto Nellie

Walker, thankfully not plummy, and Stuart Robinson, who is laudable

too. The choir is the Philharmonic Chorus, trained by the expert

Charles Kennedy Scott. They made a number of recordings together,

much valued to this day. In any case Coates was used to directing

choirs and one of his most interesting recordings, made the

previous year, was of Bax’s Mater Ora Filium with the

Leeds Festival Chorus.

There is more, besides. Elgar’s grandiloquently thrilling Bach

reworking is meat and drink to a musical hedonist like Coates

– though it would be wrong to think him, from this description,

as undisciplined. It’s remarkable, in fact, how successful he

was in the recording studio, when he had to channel his intense,

romantic style in four minute segments. More Beethoven completes

the disc, a rare outing for the rather emaciated 1925 Gratulations-Menuett

WoO 3 (has anyone else transferred it?) and the Prometheus

overture, via a far richer 1927 HMV.

There is a competing Ninth on Historic Recordings 47, but I’ve

not had access to it, and it doesn’t contain any fillers. Ward

Marston has done a fine job with the Victors for the Ninth,

and Coatesians may apply with absolute confidence.

Jonathan Woolf