This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Coolidge's Address

A century ago, the adoption of electrical recording by major labels on both sides of the Atlantic revolutionized the industry. The old method of recording acoustically through a horn-like apparatus had remained fundamentally unchanged since Edison’s invention of 1877, nearly 50 years earlier. With electrical recording, the frequency range captured on disc was greatly expanded. Instrumentalists and singers now sounded more realistic, and there was no longer a need to rescore orchestral music in order to reinforce the bass using tubas (although at first this continued to be done to accommodate acoustic reproducers). Full symphony orchestras and choruses of hundreds of singers could now be recorded. Moreover, recordings could now be taken outside small studios and into large concert halls, even into the open air.

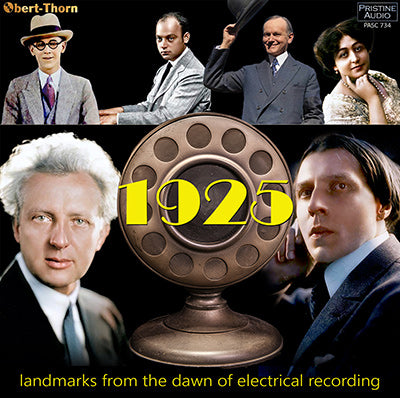

To celebrate this sea change in recording history, Pristine presents in this release the landmark discs from 1925 that forever altered the way people listened to records. All of the major discs that appeared during that year and have long been mentioned in books like Roland Gelatt’s The Fabulous Phonograph (1954; rev. 1977) are here. This development, however, did not come out of nowhere; and our release also features some of the steps that led up to the “electric year”. Also included is the first complete release of all that was recorded of Calvin Coolidge’s Presidential Inauguration ceremony, transferred from rare test pressings.

While claims regarding the “earliest recorded electrical” this or “first issued electrical” that continue to be disputed, one fact that historians have agreed upon is that the first issued electrical recording was made on Armistice Day, 1920, at Westminster Abbey during the ceremony for the interment of the Unknown Warrior of World War I. British engineers Lionel Guest and H. O. Merriman had developed a system utilizing something similar to the speaking end of a telephone as a microphone, transmitting the signal via phone lines to an offsite cutting turntable.

The resultant signal was dim, nearly overwhelmed by the surface noise of the record, and muddied by the vast reverberant space of the church in which it was recorded. (The cutting turntable had not yet come up to speed when "Abide with me" began to be recorded, resulting in the fall in pitch heard as the record begins.) Still, the melodies of the hymns can be clearly discerned, as well as the fact that people are singing (although the text cannot be made out) and that instruments were playing. The record was issued by English Columbia, and sold locally as a fundraiser for the church; but the experiment proved to be a dead end for this system, although it did spur English Columbia to further experimentation in electrical recording over the next few years.

(A note about the pitching of these tracks is in order. At this time, Royal bands still tuned to the Victorian-era “high pitch” of A4=452 Hz. Since the Grenadier Guards would not retire their older instruments until 440 Hz was standardized for Royal bands in 1927, these two tracks have been pitched higher than the others in this release.)

The next two tracks shed light on a pioneer of electrical recording whose work had been largely ignored by (or perhaps unknown to) audio historians until recent years. Orlando R. Marsh was a Chicago-based engineer who developed an electrical system and began issuing recordings using it on his own Autograph label as early as 1922. One of the first performers to gain fame from this source was silent movie house organist Jesse Crawford, who began a forty-year recording career with these discs. Using the old acoustic system with its limited frequency range, it was thought to be impossible to capture the sound of an organ. Marsh was able to accomplish this with his system, even recording Crawford on-site in the large cinema in which he regularly played. Marsh’s system, however, had variable results. The following track, featuring Dell Lampe’s Orchestra (at the time, Chicago’s highest-paid and most popular local dance band) is not quite as successful, exhibiting a more restricted frequency range commonly associated with acoustic recordings.

Since 1919, Western Electric, the commercial research and development arm of Bell Laboratories, had been attempting to develop electrical recording under the direction of Joseph P. Maxfield and Henry C. Harrison. Part of their experiments involved recording broadcast concerts of the New York Philharmonic via direct radio lines. (Pristine has already released several sides recorded in that manner from an April, 1924 concert conducted by Willem Mengelberg on PASC 184.) By late 1924, they had made sufficient progress to offer their system to the two major labels in America, Victor and Columbia. In the same month that Marsh’s Dell Lampe recording was made, Columbia had one of their featured pianists, Mischa Levitzki, make the test recording of Chopin presented here. Even through the surface noise of this unique test pressing, the gain in frequency range and presence is audible.

Surprisingly, Western Electric’s offer at first did not attract any takers. American Columbia was nearly broke and couldn’t afford the licensing fee and royalties being demanded, while Victor’s management had an almost pathological aversion to anything related to its growing competitor, radio, including the use of microphones. It was only after a disastrous Christmas sales season at the end of 1924 that Victor bit the bullet and became open to the offer.

In the meantime, the manager of the New York plant where Western Electric was having its test records pressed surreptitiously sent copies of some of the discs to an old friend in England – Louis Sterling, the head of English Columbia. The package arrived on Christmas Eve, 1924, and Sterling auditioned the discs on Christmas day. The following day, he was aboard the first ship he could book to New York, eager to cut a deal with WE. For their part, WE insisted that the rights could only be granted to an American company; so Sterling swiftly obtained a loan to buy a controlling interest in American Columbia. Shortly afterward, Victor signed up, as well.

By early February, 1925, Victor had set up a special studio in Camden to work exclusively on test recordings using the new system. The Giuseppe De Luca recording included here, from a test pressing unpublished on 78 rpm, was made during this interim period. (British record collector and researcher Jolyon Hudson has identified several sides believed to stem from these trials that were sent over to HMV after March, 1925 and issued in England. However, because Victor did not include recording matrix or date data for these electric tests in its surviving logs, it is impossible to know with certainty whether these sides predate the label’s first electrical releases.)

By the end of February, Victor was ready to proceed with recording electrically with a view to publish. However, they were pipped to the post by rival Columbia, who made two sides which, coupled on a single disc, became the earliest Western Electric process electrical recordings to be issued. Art Gillham, who was billed as “The Whispering Pianist”, had made a successful career on the radio with his intimate, confessional singing, presaging the kind of “crooning” that electrical recording would make possible and which would change the direction of popular singing. Sibiliants that could never be recorded acoustically could finally be heard. Gillham (who was neither fat nor bald, as he described himself in “I had someone else”, but rather resembled silent film comedian Harold Lloyd, even down to his trademark glasses) was surprised when Columbia granted him a bonus of one thousand dollars – then a princely sum – to have been their electrical guinea pig.

The very next day, Victor recorded its own earliest electrical disc to be issued, featuring several of its best-selling popular acts on what amounts to an elaborate demo record. Acts which had been recording for over a decade, like Billy Murray, the Peerless Quartet and the Sterling Trio, were placed side-by-side with jazz instrumentalists and a dialect comedian, performing operetta arias, Victorian-era ballads and plantation songs – a true snapshot of mainstream American popular culture of the time. (The reference to Henry Ford here was not due to his musical accomplishments – although he was an avid fan of country fiddling who owned an array of rare violins, including Stradivari – but to the nickname of his famed Model T, the “Tin Lizzie”.)

But “earliest recorded” is not always “first issued”; and the prize for that goes to the two tracks that follow. Someone at the University of Pennsylvania’s theatrical Mask and Wig Club must have known someone at Victor; for how else could they have gotten a recording made of highlights from their latest annual musical, Joan of Arkansas, with members of their all-male glee club backed by Nat Shilkret and Victor’s crack band? Suffice it to say that the mid-March recording made it to local Philadelphia stores by April, and the rest is history.

Victor and Columbia had agreed that no mention would be made of the new electrical process prior to November. Both companies had sizeable stocks of existing acoustic recordings in the catalog and new ones waiting to be released, most of which would be considered obsolete once the new technology was identified. (English Columbia had been in the midst of a major program of recording complete Classical works – symphonies and chamber music – acoustically, and would be the most harmed by the changeover.) Nonetheless, reviewers who knew what was up found ways to indicate that these records had a startlingly new presence without violating the ban.

The next six tracks document “firsts” of different varieties. Contralto Margarete Matzenauer set down two sides on March 18th which became the earliest-recorded issued vocal sides made by a Classical artist using the Western Electric process. They were coupled with sides recorded the following day and issued on separate discs (one ten-inch, the other twelve). Although her vibrato was a bit wide by this point in her career, the power behind her high notes is certainly made clear by the new technology.

The following tracks by pianist Alfred Cortot were coupled on the Victor’s first electrical Red Seal release (6502). Oddly, the HMV issue of the Chopin Impromptu coupled it with the second half only of Chopin’s G-minor Ballade, and this version of Cortot’s Schubert song transcription was not released in Europe at all. (Neither was the “Ballade Fragment”, as it was billed, released in the U.S.)

The next two tracks come from a ten-inch side which was part of a set of two discs (the other twelve-inch) containing Bizet’s complete Petite Suite, his orchestrated version of several numbers drawn from his piano collection, Jeux d’enfants. It demonstrates that Victor had already recorded a Classical orchestral work over a month before Stokowski would conduct his own first Victor electric, Danse Macabre. Surprisingly, both discs of the Bizet, the uncredited work of Victor house conductor Josef Pasternack, would remain in the catalog until the end of the 78 rpm era.Perhaps no other single disc helped to sell the public on the new process more than Columbia’s Associated Glee Clubs of America coupling of “John Peel” and “Adeste Fidelis”. During the acoustic era, one was likely to encounter on disc a chorus of eight voices (the number used in Albert Coates’ 1923 recording of the Beethoven Ninth), about as many as could fit in a small recording studio alongside a reduced orchestra. But the Columbia release, recorded during a live performance at the old Metropolitan Opera House in New York, boasted 850 voices for “John Peel” and a whopping additional 4,000 voices for “Adeste”, counting the total number of the audience that was invited to join in for the final verse. (Truth be told, no more voices can be discerned on this track than on the other, possibly because the rather directional microphone used was focused on what was happening onstage, not in the audience.) As Roland Gelatt wrote in The Fabulous Phonograph,

It was staggeringly loud and brilliant (as compared to anything made by the old method), it embodied a resonance and sense of “atmosphere” never before heard on a phonograph record, and it sold in the thousands. Although [it] was not the very first electrical recording to reach the public, it was the first one to dramatize the revolution in recording and the first to make a sharp impression on the average record buyer.

The focus on the Western Electric system has all but obscured the short-lived rival process developed by General Electric, the so-called “Light-Ray” system, used by its licensees Brunswick and Grammophon/Polydor until 1927. This employed a beam of light to convey electrical impulses to the disc cutting head. The Prelude from Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana included here was the earliest issued Brunswick electrical recording (noted by the “E” in the “XE” matrix prefix). The general drawback of this system was that it tended to distort at higher volume levels, although it works well in this mostly quiet music.

Following this track is what history books have generally cited as the earliest electrical recording of a symphony orchestra (although, as we’ve seen, it was predated by both Brunswick and Victor itself). Leopold Stokowski’s disc of Saint-Saëns’ Danse Macabre utilized the same kind of rescoring that was done for acoustic sessions in order to bolster bass frequencies for acoustic horn reproducers. Here, string basses were replaced by a tuba, and a contrabassoon substituted for the tympani, giving the resulting performance a weirder, even more disconcerting sound than the composer originally intended.

On May 15th, Stokowski began recording Dvořák’s New World Symphony. Had he finished it around that time, it would have been the first electrical recording of a symphony. As it was, however, the sessions continued through December; and by then, Sir Landon Ronald’s electrical set of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony had been released in the UK. Ronald conducted the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra from its start (as the New Symphony Orchestra) in 1908 until its dissolution in 1928. He recorded extensively for HMV throughout his career, both as conductor and piano accompanist.

His Tchaikovsky Fourth, recorded at HMV’s Hayes studios in July of 1925, uses tuba reinforcement for the string basses (as HMV would continue to do through at least early 1927), although we are spared Stokowski’s contrabassoon in lieu of the tympani, a decided advantage at the ends of the outlying movements. Ronald could be a variable interpreter, but here he turns in an exciting and highly satisfying performance which checks all the right boxes. Gramophone’s editor Compton Mackenzie was not pleased, however, writing that there seemed to be “something almost deliberately defiant in choosing this particular work for a symphonic debut in the latest methods of recording,” citing the music itself being “a jangle of shattered nerves” which was only magnified by the harshness of the new process. It would take the changeover to electrical reproducers to enable listeners to fully appreciate what the new records could convey.

Placed at the end of our survey for programming purposes is another example of what the electrical process could now capture. When the previous U.S. presidential election had taken place in 1920, radio was in its infancy, and only the results of the polls were broadcast as they came in. By March, 1925, a presidential inauguration could not only be sent out as it happened on the radio, but also simultaneously preserved for posterity on an electrical recording.

Bell Laboratories spared no expense for this technological demonstration. Loudspeakers were installed at school auditoriums throughout the country for students to hear the broadcast live, and seven sides were recorded from the direct line. No attempt was made to record the complete speech, which was twice as long as the extant excerpts. Comparing the records to the complete text of Coolidge’s speech (reproduced on the webpage for this release) shows how much was left out. The transfer here from unpublished test pressings is complete as recorded, with only some lengthy spots of “dead air” edited out. Portions have previously appeared online, but this is the first publication of the entire recording, including the oath of office given by Supreme Court Chief Justice (and former President) William Howard Taft in his only electrical recording, and the U.S. Marine Band playing “Hail to the Chief” at the end.

Mark Obert-Thorn, January, 2025

1925: Landmarks from the Dawn of Electrical Recording

Disc 1 (66:09)

1. MONK Abide with me (2:50)

2. DYKES Recessional (3:34)

Choir, Congregation and Band of H. M. Grenadier Guards

Recorded 11 November 1920 in Westminster Abbey, London ∙ Matrices: unknown ∙

First issued on unnumbered Columbia “Memorial Record”

3. JONES & KAHN The one I love belongs to somebody else (3:17)

Jesse Crawford, organ

Recorded c. December, 1923 in the Chicago Theater, Chicago ∙ Matrix: 447 ∙

First issued on Autograph (no catalog number)

Dell Lampe Orchestra from the Trianon Ballroom/Al Dodson, vocal chorus

Recorded c. November, 1924, Chicago ∙ Matrix: 658 ∙ First issued on

Autograph 604

Mischa Levitzki, piano

Recorded 19 November 1924, New York ∙ Matrix: 6466-1 ∙ Columbia (unpublished

on 78 rpm)

6. CIMARA Stornello (Son come i chicchi) (3:03)

Giuseppe De Luca, baritone/Orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon

Recorded 17 February 1925, Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: WER-3719 ∙ Victor

(unpublished on 78 rpm)

8. STANLEY, HARRIS & DARCEY I had someone else before I had you*

(3:17)

Art Gillham, piano and vocal

Recorded 25 February 1925 in New York ∙ Matrices: 140125-7 & *140394-2

∙ First issued on Columbia 328-D

9. THE EIGHT POPULAR VICTOR ARTISTS A miniature concert (9:29)

Opening Chorus; “Strut Miss Lizzie” – Frank Banta, piano; “Love’s old sweet

song” – Sterling Trio; “Friend Cohen” – Monroe Silver, speaker; “When you

and I were young, Maggie” – Henry Burr, tenor; “Casey Jones” – Billy Murray,

tenor and Chorus; “Sweet Genevieve” – Albert Campbell, tenor and Henry Burr,

tenor; “Saxophobia” – Rudy Wiedoeft, saxophone; “Gypsy Love Song” – Frank

Croxton, bass; “Carry me back to old Virginny” – Peerless Quartet; “Massa’s

in de cold, cold ground” – Chorus

Recorded 26 February 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CVE 31874-3 and

31875-4 ∙ First issued on Victor 35753

10. GILPIN Joan of Arkansas – Medley (3:15)

Mask and Wig Glee Chorus; Orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret

Recorded 16 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: BVE 32160-2 ∙ First

issued on Victor 19626

11. GILPIN Joan of Arkansas – Buenos Aires (3:37)

Arthur Hall, tenor; Bernard Baker, cornet solo; International Novelty

Orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret

Recorded 20 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: BVE 32170-2 ∙ First

issued on Victor 19626

12. MEYERBEER Le prophète – Ah, mon fils! (4:36)

13. MEXICAN FOLK SONG Pregúntales á las estrellas* (3:23)

Margarete Matzenauer, contralto; Orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon

Recorded 18 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CVE 31632-3 and

*BVE 31629-4 ∙ First issued on Victor 6531 and *1080

15. CHOPIN Impromptu No. 2 in F sharp major, Op. 36* (4:41)

Alfred Cortot, piano

Recorded 21 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CE 22512-11 and

*31689-5 ∙ First issued on Victor 6502

BIZET Petite suite (from Jeux d’enfants)

16. 1st Mvt.: Marche (2:09)

17. 3rd Mvt.: Impromptu (1:03)

Victor Concert Orchestra conducted by Josef Pasternack

Recorded 23 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: BE 32179-3 ∙ First

issued on Victor 19730

19. WADE Adeste fideles* (2:43)

Associated Glee Clubs of America

Recorded 31 March 1925 in the Metropolitan Opera House, New York ∙ Matrices:

W98163-1 and *W98166-1 ∙ First issued on Columbia 50013-D

Disc 2 (74:13)

1. MASCAGNI Cavalleria rusticana - Prelude (4:45)

Metropolitan Opera Orchestra conducted by Gennaro Papi

Recorded 8 April 1925 in Room No. 3, 799 Seventh Avenue, New York ∙ Matrix:

XE 15472 or 15473 ∙ First issued on Brunswick 50067

Thaddeus Rich, solo violin

The Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Leopold Stokowski

Recorded 29 April 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CVE 27929-2 &

27930-2 ∙ First issued on Victor 6505

TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36

3. 1st Mvt.: Andante sostenuto (17:38)

4. 2nd Mvt.: Andantino in modo di canzona (7:51)

5. 3rd Mvt.: Scherzo: Pizzicato ostinato (5:22)

6. 4th Mvt.: Allegro con fuoco (8:45)

Royal Albert Hall Orchestra conducted by Sir Landon Ronald

Recorded 20, 21 & 27 July 1925 in Hayes, Middlesex ∙ Matrices: Cc

6374-2, 6375-3, 6376-3, 6377-2, 6378-2, 6379-2, 6381-1, 6410-1, 6380-5 &

6382-2 ∙ First issued on HMV 1037/41

Inauguration of Calvin Coolidge as President of the United States

7. Oath of Office (given by Chief Justice William Howard Taft) (0:57)

8. “My Countrymen . . .” (2:04)

9. “It will be well not to be too much disturbed . . .” (3:28)

10. “Our private citizens have advanced large sums of money . . .” (3:33)

11. “There is no salvation in a narrow and bigoted partisanship” (3:25)

12. “. . . they ought not to be burdened . . .” (3:34)

13. “Under a despotism the law may be imposed . . .” (3:24)

14. “. . . built on blood and force” (0:51)

15. Ruffles and Flourishes/Hail to the Chief (U.S. Marine Band) (1:11)

Calvin Coolidge, speaker

Recorded 4 March 1925 in Washington, D.C. ∙ Matrices: 51175/81 ∙ Columbia

(unpublished on 78 rpm)

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Special thanks to Gregor Benko, Jim Cartwright’s Immortal Performances, Inc., Cate Gasco, Colin Hancock, Ward Marston, David Mason, Dave Schmutz, the collection of the late Don Tait and Lew Williams for providing source material and/or valuable guidance for this project

Total timing: 2hr 20:22

Complete text of Calvin Coolidge’s Inaugural Address, March 4, 1925

(Recorded portions shown in boldface, and side track beginnings and endings

indicated in italics within paretheses)

(Track 8 start)

MY COUNTRYMEN:

No one can contemplate current conditions without finding much that is satisfying and still more that is encouraging. Our own country is leading the world in the general readjustment to the results of the great conflict. Many of its burdens will bear heavily upon us for years, and the secondary and indirect effects we must expect to experience for some time. But we are beginning to comprehend more definitely what course should be pursued, what remedies ought to be applied, what actions should be taken for our deliverance, and are clearly manifesting a determined will faithfully and conscientiously to adopt these methods of relief. Already we have sufficiently rearranged our domestic affairs so that confidence has returned, business has revived, and we appear to be entering an era of prosperity which is gradually reaching into every part of the nation. Realizing that we can not live unto ourselves alone, we have contributed of our resources and our counsel to the relief of the suffering and the settlement of the disputes among the European nations. Because of what America is and what America has done, a firmer courage, a higher hope, inspires the heart of all humanity. (Track 8 end)

These results have not occurred by mere chance. They have been secured by a constant and enlightened effort marked by many sacrifices and extending over many generations. We can not continue these brilliant successes in the future, unless we continue to learn from the past. It is necessary to keep the former experiences of our country both at home and abroad continually before us, if we are to have any science of government. If we wish to erect new structures, we must have a definite knowledge of the old foundations. We must realize that human nature is about the most constant thing in the universe and that the essentials of human relationship do not change. We must frequently take our bearings from these fixed stars of our political firmament if we expect to hold a true course. If we examine carefully what we have done, we can determine the more accurately what we can do.

We stand at the opening of the one hundred and fiftieth year since our national consciousness first asserted itself by unmistakable action with an array of force. The old sentiment of detached and dependent colonies disappeared in the new sentiment of a united and independent nation. Men began to discard the narrow confines of a local charter for the broader opportunities of a national constitution. Under the eternal urge of freedom we became an independent nation. A little less than 50 years later that freedom and independence were reasserted in the face of all the world, and guarded, supported, and secured by the Monroe Doctrine. The narrow fringe of states along the Atlantic seaboard advanced its frontiers across the hills and plains of an intervening continent until it passed down the golden slope to the Pacific. We made freedom a birthright. We extended our domain over distant islands in order to safeguard our own interests and accepted the consequent obligation to bestow justice and liberty upon less favored peoples. In the defense of our own ideals and in the general cause of liberty we entered the Great War. When victory had been fully secured, we withdrew to our own shores unrecompensed save in the consciousness of duty done.Throughout all these experiences we have enlarged our freedom, we have strengthened our independence. We have been, and propose to be, more and more American. We believe that we can best serve our own country and most successfully discharge our obligations to humanity by continuing to be openly and candidly, intensely and scrupulously, American. If we have any heritage, it has been that. If we have any destiny, we have found it in that direction.

But if we wish to continue to be distinctively American, we must continue to make that term comprehensive enough to embrace the legitimate desires of a civilized and enlightened people determined in all their relations to pursue a conscientious and religious life. We can not permit ourselves to be narrowed and dwarfed by slogans and phrases. It is not the adjective, but the substantive, which is of real importance. It is not the name of the action, but the result of the action, which is the chief concern. (Track 9 start) It will be well not to be too much disturbed by the thought of either isolation or entanglement of pacifists and militarists. The physical configuration of the earth has separated us from all of the Old World, but the common brotherhood of man, the highest law of all our being, has united us by inseparable bonds with all humanity. Our country represents nothing but peaceful intentions toward all the earth, but it ought not to fail to maintain such a military force as comports with the dignity and security of a great people. It ought to be a balanced force, intensely modern, capable of defense by sea and land, beneath the surface and in the air. But it should be so conducted that all the world may see in it, not a menace, but an instrument of security and peace.

This nation believes thoroughly in an honorable peace under which the rights of its citizens are to be everywhere protected. It has never found that the necessary enjoyment of such a peace could be maintained only by a great and threatening array of arms. In common with other nations, it is now more determined than ever to promote peace through friendliness and good will, through mutual understandings and mutual forbearance. We have never practiced the policy of competitive armaments. We have recently committed ourselves by covenants with the other great nations to a limitation of our sea power. As one result of this, our navy ranks larger, in comparison, than it ever did before.

Removing the burden of expense and jealousy, which must always accrue from a keen rivalry, is one of the most effective methods of diminishing that unreasonable hysteria and misunderstanding which is the most potent means of fomenting war. This policy represents a new departure in the world. It is a thought, an ideal, which has led to an entirely new line of action. It will not be easy to maintain. Some never moved from their old position, some are constantly slipping back to the old ways of thought and the old action of seizing a musket and relying on force. (Track 9 end) America has taken the lead in this new direction, and that lead America must continue to hold. If we expect others to rely on our fairness and justice we must show that we rely on their fairness and justice.

If we are to judge by past experience, there is much to be hoped for in international relations from frequent conferences and consultations. We have before us the beneficial results of the Washington Conference and the various consultations recently held upon European affairs, some of which were in response to our suggestions and in some of which we were active participants. Even the failures can not but be accounted useful and an immeasurable advance over threatened or actual warfare. I am strongly in favor of a continuation of this policy, whenever conditions are such that there is even a promise that practical and favorable results might be secured.

In conformity with the principle that a display of reason rather than a threat of force should be the determining factor in the intercourse among nations, we have long advocated the peaceful settlement of disputes by methods of arbitration and have negotiated many treaties to secure that result. The same considerations should lead to our adherence to the Permanent Court of International Justice. Where great principles are involved, where great movements are under way which promise much for the welfare of humanity by reason of the very fact that many other nations have given such movements their actual support, we ought not to withhold our own sanction because of any small and inessential difference, but only upon the ground of the most important and compelling fundamental reasons. We can not barter away our independence or our sovereignty, but we ought to engage in no refinements of logic, no sophistries, and no subterfuges, to argue away the undoubted duty of this country by reason of the might of its numbers, the power of its resources, and its position of leadership in the world, actively and comprehensively to signify its approval and to bear its full share of the responsibility of a candid and disinterested attempt at the establishment of a tribunal for the administration of even-handed justice between nation and nation. The weight of our enormous influence must be cast upon the side of a reign not of force but of law and trial, not by battle but by reason.

We have never any wish to interfere in the political conditions of any other countries. Especially are we determined not to become implicated in the political controversies of the Old World. With a great deal of hesitation, we have responded to appeals for help to maintain order, protect life and property, and establish responsible government in some of the small countries of the Western Hemisphere. (Track 10 start) Our private citizens have advanced large sums of money to assist in the necessary financing and relief of the Old World. We have not failed, nor shall we fail to respond, whenever necessary to mitigate human suffering and assist in the rehabilitation of distressed nations. These, too, are requirements which must be met by reason of our vast powers and the place we hold in the world.

Some of the best thought of mankind has long been seeking for a formula for permanent peace. Undoubtedly the clarification of the principles of international law would be helpful, and the efforts of scholars to prepare such a work for adoption by the various nations should have our sympathy and support. Much may be hoped for from the earnest studies of those who advocate the outlawing of aggressive war. But all these plans and preparations, these treaties and covenants, will not of themselves be adequate. One of the greatest dangers to peace lies in the economic pressure to which people find themselves subjected. One of the most practical things to be done in the world is to seek arrangements under which such pressure may be removed, so that opportunity may be renewed and hope may be revived. There must be some assurance that effort and endeavor will be followed by success and prosperity. In the making and financing of such adjustments there is not only an opportunity, but a real duty, for America to respond with her counsel and her resources. Conditions must be provided under which people can make a living and work out of their difficulties. But there is another element, more important than all, without which there can not be the slightest hope of a permanent peace. That element lies in the heart of humanity. Unless the desire for peace be cherished there, unless this fundamental and only natural source of brotherly love be cultivated to its highest degree, all artificial efforts will be in vain. Peace will come when there is realization that only under a reign of law, based on righteousness and supported by the religious conviction of the brotherhood of man, can there be any hope of a complete and satisfying life. Parchment will fail, the sword will fail, it is only the spiritual nature of man that can be triumphant. (Track 10 end)

It seems altogether probable that we can contribute most to these important objects by maintaining our position of political detachment and independence. We are not identified with any Old World interests. This position should be made more and more clear in our relations with all foreign countries. We are at peace with all of them. Our program is never to oppress, but always to assist. But while we do justice to others, we must require that justice be done to us. With us a treaty of peace means peace, and a treaty of amity means amity. We have made great contributions to the settlement of contentious differences in both Europe and Asia. But there is a very definite point beyond which we can not go. We can only help those who help themselves. Mindful of these limitations, the one great duty that stands out requires us to use our enormous powers to trim the balance of the world.

While we can look with a great deal of pleasure upon what we have done abroad, we must remember that our continued success in that direction depends upon what we do at home. Since its very outset, it has been found necessary to conduct our Government by means of political parties. That system would not have survived from generation to generation if it had not been fundamentally sound and provided the best instrumentalities for the most complete expression of the popular will. It is not necessary to claim that it has always worked perfectly. It is enough to know that nothing better has been devised. No one would deny that there should be full and free expression and an opportunity for independence of action within the party. (Track 11 start) There is no salvation in a narrow and bigoted partisanship. But if there is to be responsible party government, the party label must be something more than a mere device for securing office. Unless those who are elected under the same party designation are willing to assume sufficient responsibility and exhibit sufficient loyalty and coherence, so that they can cooperate with each other in the support of the broad general principles of the party platform, the election is merely a mockery, no decision is made at the polls, and there is no representation of the popular will. Common honesty and good faith with the people who support a party at the polls require that party, when it enters office, to assume the control of that portion of the Government to which it has been elected. Any other course is bad faith and a violation of the party pledges.

When the country has bestowed its confidence upon a party by making it a majority in the Congress, it has a right to expect such unity of action as will make the party majority an effective instrument of government. This Administration has come into power with a very clear and definite mandate from the people. The expression of the popular will in favor of maintaining our constitutional guarantees was overwhelming and decisive. There was a manifestation of such faith in the integrity of the courts that we can consider that issue rejected for some time to come. Likewise, the policy of public ownership of railroads and certain electric utilities met with unmistakable defeat. The people declared that they wanted their rights to have not a political but a judicial determination, and their independence and freedom continued and supported by having the ownership and control of their property, not in the Government, but in their own hands. As they always do when they have a fair chance, the people demonstrated that they are sound and are determined to have a sound government.

When we turn from what was rejected to inquire what was accepted, (Track 11 end) the policy that stands out with the greatest clearness is that of economy in public expenditure with reduction and reform of taxation. The principle involved in this effort is that of conservation. The resources of this country are almost beyond computation. No mind can comprehend them. But the cost of our combined governments is likewise almost beyond definition. Not only those who are now making their tax returns, but those who meet the enhanced cost of existence in their monthly bills, know by hard experience what this great burden is and what it does. No matter what others may want, these people want a drastic economy. They are opposed to waste. They know that extravagance lengthens the hours and diminishes the rewards of their labor. I favor the policy of economy, not because I wish to save money, but because I wish to save people. The men and women of this country who toil are the ones who bear the cost of the Government. Every dollar that we carelessly waste means that their life will be so much the more meager. Every dollar that we prudently save means that their life will be so much the more abundant. Economy is idealism in its most practical form.

If extravagance were not reflected in taxation, and through taxation both directly and indirectly injuriously affecting the people, it would not be of so much consequence. The wisest and soundest method of solving our tax problem is through economy. Fortunately, of all the great nations this country is best in a position to adopt that simple remedy. We do not any longer need war-time revenues. The collection of any taxes which are not absolutely required, which do not beyond reasonable doubt contribute to the public welfare, is only a species of legalized larceny. Under this republic the rewards of industry belong to those who earn them. The only constitutional tax is the tax which ministers to public necessity. The property of the country belongs to the people of the country. Their title is absolute. They do not support any privileged class; they do not need to maintain great military forces; (Track 12 start) they ought not to be burdened with a great array of public employees. They are not required to make any contribution to Government expenditures except that which they voluntarily assess upon themselves through the action of their own representatives. Whenever taxes become burdensome a remedy can be applied by the people; but if they do not act for themselves, no one can be very successful in acting for them.

The time is arriving when we can have further tax reduction, when, unless we wish to hamper the people in their right to earn a living, we must have tax reform. The method of raising revenue ought not to impede the transaction of business; it ought to encourage it. I am opposed to extremely high rates, because they produce little or no revenue, because they are bad for the country, and, finally, because they are wrong. We can not finance the country, we can not improve social conditions, through any system of injustice, even if we attempt to inflict it upon the rich. Those who suffer the most harm will be the poor. This country believes in prosperity. It is absurd to suppose that it is envious of those who are already prosperous. The wise and correct course to follow in taxation and all other economic legislation is not to destroy those who have already secured success but to create conditions under which every one will have a better chance to be successful. The verdict of the country has been given on this question. That verdict stands. We shall do well to heed it.

These questions involve moral issues. We need not concern ourselves much about the rights of property if we will faithfully observe the rights of persons. Under our institutions their rights are supreme. It is not property but the right to hold property, both great and small, which our Constitution guarantees. All owners of property are charged with a service. These rights and duties have been revealed, through the conscience of society, to have a divine sanction. The very stability of our society rests upon production and conservation. For individuals or for governments to waste and squander their resources is to deny these rights and disregard these obligations. (Track 12 end) The result of economic dissipation to a nation is always moral decay.

These policies of better international understandings, greater economy, and lower taxes have contributed largely to peaceful and prosperous industrial relations. Under the helpful influences of restrictive immigration and a protective tariff, employment is plentiful, the rate of pay is high, and wage earners are in a state of contentment seldom before seen. Our transportation systems have been gradually recovering and have been able to meet all the requirements of the service. Agriculture has been very slow in reviving, but the price of cereals at last indicates that the day of its deliverance is at hand.

We are not without our problems, but our most important problem is not to secure new advantages but to maintain those which we already possess. Our system of government made up of three separate and independent departments, our divided sovereignty composed of Nation and State, the matchless wisdom that is enshrined in our Constitution, all these need constant effort and tireless vigilance for their protection and support.

In a republic the first rule for the guidance of the citizen is obedience to law. (Track 13 start) Under a despotism the law may be imposed upon the subject. He has no voice in its making, no influence in its administration, it does not represent him. Under a free government the citizen makes his own laws, chooses his own administrators, which do represent him. Those who want their rights respected under the Constitution and the law ought to set the example themselves of observing the Constitution and the law.

While there may be those of high intelligence who violate the law at times, [the] barbarian and the defective always violate it. Those who disregard the rules of society are not exhibiting a superior intelligence, are not promoting freedom and independence, are not following the path of civilization, but are displaying the traits of ignorance, or servitude, of savagery, and treading the way that leads back to the jungle.

The essence of a republic is representative government. Our Congress represents the people and the states. In all legislative affairs it is the natural collaborator with the President. In spite of all the criticism which often falls to its lot, I do not hesitate to say that there is no more independent and effective legislative body in the world. It is, and should be, jealous of its prerogative. I welcome its cooperation, and expect to share with it not only the responsibility, but the credit, for our common effort to secure beneficial legislation.

These are some of the principles which America represents. We have not by any means put them fully into practice, but we have strongly signified our belief in them. The encouraging feature of our country is not that it has reached its destination, but that it has overwhelmingly expressed its determination to proceed in the right direction. It is true that we could, with profit, be less sectional and more national in our thought. It would be well if we could replace much that is only a false and ignorant prejudice with a true and enlightened pride of race. But the last election showed that appeals to class and nationality had little effect. (Track 13 end) We were all found loyal to a common citizenship. The fundamental precept of liberty is toleration. We can not permit any inquisition either within or without the law or apply any religious test to the holding of office. The mind of America must be forever free.

It is in such contemplations, my fellow countrymen, which are not exhaustive but only representative, that I find ample warrant for satisfaction and encouragement. We should not let the much that is to do obscure the much which has been done. The past and present show faith and hope and courage fully justified. Here stands our country, an example of tranquillity at home, a patron of tranquillity abroad. Here stands its Government, aware of its might but obedient to its conscience. Here it will continue to stand, seeking peace and prosperity, solicitous for the welfare of the wage earner, promoting enterprise, developing waterways and natural resources, attentive to the intuitive counsel of womanhood, encouraging education, desiring the advancement of religion, supporting the cause of justice and honor among the nations. America seeks no earthly empire (Track 14 start) built on blood and force. No ambition, no temptation, lures her to thought of foreign dominions. The legions which she sends forth are armed, not with the sword, but with the cross. The higher state to which she seeks the allegiance of all mankind is not of human, but of divine origin. She cherishes no purpose save to merit the favor of Almighty God. (Track 14 end)