- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

When Jascha Heifetz performed these two concertos on 1 April 1949 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussevitzky he almost certainly did not know that he was being recorded. The regular broadcasts of the BSO had been transferred from the NBC Blue to the new ABC network in 1945, but this arrangement only lasted a season. BSO concerts were not broadcast nationally again until 1954 when NBC was looking for a ready replacement for its own NBCSO broadcasts after Toscanini’s retirement. So, who recorded this concert, and several others from the 1948-9 season? It turns out this was an early ‘bootleg’ recording made by the owner of a Boston recording studio who set up a microphone in a ventilating grill on the right of the stage, with a link to his disc-cutting machines. There was apparently no thought of exploiting the recordings for commercial gain, but copies gradually began to circulate among enthusiasts. As direct line recordings, albeit with less than optimum microphone placings, they do not suffer from the limitations of an aircheck and offer surprisingly clear and detailed reproduction.

The Bell Telephone Hour began in 1940 and continued on NBC radio until 1958. The usual format was to have a guest artist perform alongside the resident orchestra. The 30 minute format (despite the name of the show!) did not really allow for long pieces to be played, so singers or instrumentalists performed a number of shorter items, while the orchestra played equally short pieces in between. Jascha Heifetz was a very frequent guest on the programme and played a wide variety of popular music. Over the course of two programmes, separated by two years, he played the entire Mendelssohn violin concerto which is presented here, finally united, for the first time.

Jascha Heifetz was one of the twentieth century’s finest violinists and reviews of his concert performances in the American press had little but unrelenting praise to offer. He was ‘the king of the violinists’ whose ‘impeccable virtuosity’ was unmatched. In 1937 he even attracted a record audience to a New York Philharmonic concert held at Lewishon Stadium of 18,294. These three concertos showcase the sheer breadth of Heifetz’s talent. Mozart’s Violin Concerto No.4 was composed in 1775, Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto was finished in 1844, while Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No.2 was written in 1935. Heifetz is easily able to transition between the classical, romantic and modern styles and, of course, each concerto offers him the chance to display the virtuosity he was famed for. The beauty of these live recordings is that we can appreciate Heifetz caught in the moment, and in the case of the BSO recordings, completely uninhibited by the thought of a microphone. We can hear precisely what he wanted his audience to hear that night.

HEIFETZ Three Violin Concertos

MOZART Violin Concerto No. 4 in D, K.218

1. 1st mvt - Allegro (8:01)

2. 2nd mvt - Andante cantabile (6:26)

3. 3rd mvt - Rondeau: Andante grazioso (6:45)

PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2, Op. 63

4. 1st mvt - Allegro moderato (9:16)

5. 2nd mvt - Andante assai (8:05)

6. 3rd mvt - Allegro ben marcato (5:55)

Boston Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Serge Koussevitzky

MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto, Op. 64

7. 1st mvt - Allegro molto appassionato (11:02)

8. 2nd mvt - Andante (7:01)

9. 3rd mvt - Allegretto non troppo - Allegro molto vivace (5:59)

Bell Telephone Orchestra

conducted by Donald Voorhees

Jascha Heifetz, violin

XR remastering by

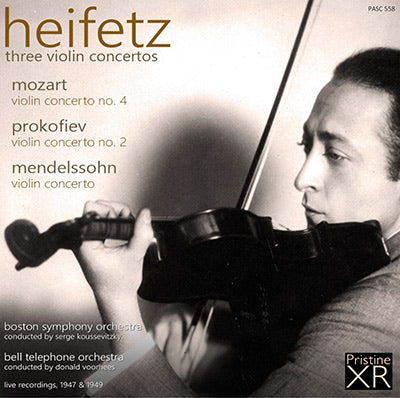

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Jascha Heifetz

Mozart & Prokofiev Concertos

Recorded 1 April 1949

Symphony Hall, Boston

Mendelssohn Concerto

1st mvt.: Recorded 26 June 1949

2nd & 3rd mvts: Recorded 20 January 1947

NBC Studio 6B(?), Radio City, New York

Total duration: 68:30

Fanfare magazine review

For those who love Heifetz, this must be the kind of thing they’ll love. Again, urgently recommended. Essential

Heifetz liked Mozart’s Fourth Violin Concerto and

he championed Prokofiev’s, so listeners here enjoy the combination of

Heifetz unedited in repertoire congenial and very much to his liking. He

would record Mozart’s concerto in the studio on November 10 of the same

year with Thomas Beecham and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and would

do so again with Malcolm Sargent on May 14 and 16, 1962. Of the three

readings, then, this “bootleg” represents the earliest. Yet, as

Even the combination of lower register and the concealed microphone can’t irretrievably bury Heifetz’s smoldering opening solo in Prokofiev’s Second Violin Concerto—nor the searing lyrical passagework with which Heifetz spins out the thematic implications of that opening. He’s incisive in the movement’s swirling middle section; and if his readings sounded progressively desiccated as he grew older—and that’s an arguable proposition—that process obviously hadn’t begun by April 1, 1949. (His other recordings of the work come from December 20, 1937 with the same conductor and orchestra and from February 24, 1959, again with the Boston orchestra, but this time under Charles Munch.) The second movement’s contrasts of the hypnotically melodic and the abrasively bristling prove more effective than they would, at least, in the later issue. Heifetz’s dominant personality surmounts the last movement’s aggressively thumping orchestral interjections. His mastery of the incisive passagework has always given him something of an edge in this work, so it’s a privilege to enjoy it unprocessed. The ending is simply overwhelming.

Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, especially its last movement, served as a calling card for Heifetz (he left it in Let Them Have Music);

its first movement sounds urgently alive in this Bell Telephone Hour

performance. After hearing the two covertly recorded performances, it’s

almost startling to hear Heifetz’s opulent sound emerge again at the

orchestra’s fore. This recording took place on June 26, 1949; just about

two weeks earlier, Heifetz had made his first recording of the work

with Thomas Beecham and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (a second would

follow about nine years later with Charles Munch and the Boston

Symphony Orchestra on February 23 and 25, 1959). Heifetz’s energy in the

broadcast seems much higher than it would later, and the close miking

allows listeners to take a front-row seat, hearing with crystal clarity

the snap of his bow and of his attack in the cadenza. The last two

movements come from January 20, 1947; the recorded sound represents

Heifetz at similarly close range, so vibrant that some listeners may

wonder why he tolerated what engineers would do to his studio recordings

later (consider how warmly commanding

Back to the prematurely rendered judgment, resoundingly reaffirmed: For those who love Heifetz, this must be the kind of thing they’ll love. Again, urgently recommended. Essential.

Robert Maxham