This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

Composed in 1931–34 and dedicated to Arnold Bax, the Fourth Symphony of Vaughan Williams notoriously represents for many listeners a bewildering departure from his usual compositional style. Although fellow composers waxed enthusiastic – William Walton supposedly said that it was “the greatest symphony since Beethoven” – critical reception was far cooler. Writing in The Manchester Guardian on April 11, 1935, the day after the premiere, Neville Cardus opined: “Vaughan Williams is becoming an enigma. A few years ago he was one of our purest melodists, drawing his simple accents from English folk-tunes. To-day he is everything but a melodist. His new symphony, played superbly to-night by the B.B.C. Orchestra under Dr. Boult, has many admirable orchestral qualities, but a man might as well hang himself as look in the work for a great tune or theme…. I decline to believe that a symphony can be made out of a method, plus gusto.”

The Fourth represents a departure from the essentially poetic and discursive veins of RVW’s first three symphonies: It is far more taut and abstract, more academically rigorous in its formal procedures, as well as far more jagged and bitingly dissonant in its thematic contours and harmonics. As in the Piano Concerto from 1926–31, one hears the composer grappling with the compositional idioms of Bartók and Hindemith. The score’s “meaning” remains controversial. Its blazing fierceness often later would be seen as prophetic of the catastrophes of totalitarianism and war soon about to engulf Europe. In an October 1958 essay in the Musical Times, Boult asserted that RVW “foresaw the whole thing [i.e. war] and surely there is no more magnificent gesture of disgust in all music than the final open fifth when the composer seems to rid himself of the whole hideous idea.” But in a letter from December 1937, RVW denied such associations: “I wrote it not as a definite picture of anything external – e.g. the state of Europe – but simply because it occurred to me like this.” On the other hand, RVW’s biographer Michael Kennedy saw the work as “a kind of self-portrait: the towering rages of which Vaughan Williams was capable, his robust humour, his poetic nature,” and a friend wrote to RVW after the premiere that “I recognized your poisonous temper in the scherzo.” Perhaps the best and last word is the composer’s exasperated rejoinder, “It never seems to occur to people that a man might just want to write a piece of music.”

The Fifth Symphony, composed between 1938 and 1943, is the Fourth’s antipode in spirit and temperament, though structurally both works employ cyclical forms, with the finales bringing back materials from the opening movements. However, rather than reverting back to the style of the first three symphonies, the Fifth instead moved forward to break new ground as one of RVW’s most spiritually profound works. The composer had been laboring since 1906 on an opera based on John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress; doubtful of its completion (he would finally finish it in 1949), he recycled some of its materials into music for a dramatic radio presentation and this symphony. Although not printed in the published version, the manuscript of the Romanza third movement that forms the heart of the work quotes the following lines from Bunyan’s work: “Upon that place there stood a cross, And a little below a sepulchre … Then he said, ‘He hath given me rest by his sorrow and Life by his death.’” Frank Howes, writing in The Times on 25 June 1943, the day after the premiere under RVW’s baton, rightly discerned that the work is “therefore essentially apocalyptic, but in the only way possible to the composer, that of quiet contemplation, not of a sudden or dramatic revelation. It seems to absorb into itself and sum up all that he has ever written, and to give us a restatement of his whole philosophy now proved by life’s experience. It is not too much to say that this belongs to that small body of music that, outside of late Beethoven, can properly be described as transcendental.” Due to wartime difficulties in communications, the score’s frontispiece reads, “Dedicated without permission to Jean Sibelius.” Boult subsequently secured Sibelius’s consent, and after hearing a broadcast performance the Finnish composer wrote: “This Symphony is a marvelous work.... The dedication made me feel proud and grateful.”

JAMES ALTENA

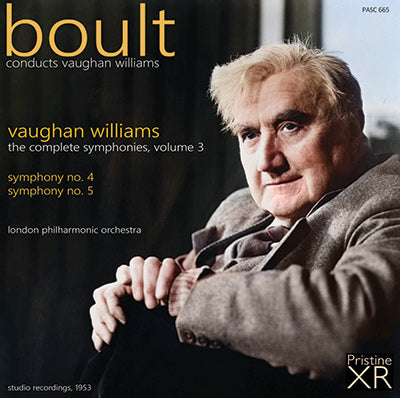

BOULT Vaughan Williams Symphonies, Volume 3

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No.4 in F minor

1. 1st mvt. - Allegro (9:10)

2. 2nd mvt. - Andante moderato (10:10)

3. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo. Allegro molto (5:44)

4. 4th mvt. - Finale con epilogo fugato. Allegro molto (9:31)

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No.5 in D major

5. 1st mvt. - Preludio. Moderato (11:01)

6. 2nd mvt. - Scherzo. Presto (4:58)

7. 3rd mvt. - Romanza. Lento (10:58)

8. 4th mvt. - Passacaglia. Moderato (10:23)

London Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Sir Adrian Boult

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Vaughan Williams

Recorded 2, 3 & 5 December 1953, Kingsway Hall, London

Produced by John Culshaw & James Walker

Engineered by Kenneth Wilkinson

Recordings supervised by the composer

Total duration: 71:55