This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

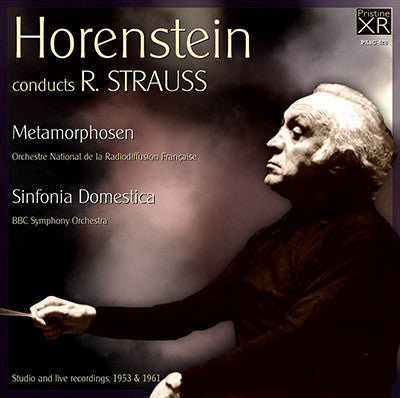

Rare Horenstein Strauss: first ever release for Sinfonia Domestica

"Much gratitude is due Pristine Audio for this immensely gratifying release"

- Fanfare

Jascha Horenstein made three records for EMI and its affiliates; his 1953 Metamorphosen, coupled with Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms (PASC 418) was one. This is its first reissue in any format - despite it winning a prestigious Grand Prix du Disque in 1954. That original recording was reasonably well-made but a lack of depth meant the lower instruments tended to get somewhat lost amidst the denser textures of the piece. XR remastering has helped here in clarifying the multiple voices of the 23 strings, adding body to the recording as well as a sense of dimension.

The 1961 BBC broadcast of Sinfonia Domestica originated in an off-air tape recording of a BBC Home Service broadcast. It is the first time a recording of Horenstein conducting this work has been made available, and once more we are grateful to the conductor's cousin, Misha Horenstein, for access to his extensive archives. The fidelity of the recording is lower than that of the earlier EMI LP, and in addition there was a degree of tape dropout to battle against during the first ten minutes or so of this 45-minute performance.

The sound quality throughout is, in this remastered version, a significant step up from the original source, as Mr. Horenstein acknowledged on first hearing it: "I agree that the first section is sonically more subdued than the later parts, but taken as a whole what you've managed to do with it is pretty impressive, bravo!"

Andrew Rose

Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion Française

Jascha Horenstein, conductor

Recorded 30 June, 1953

Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, Paris

Issued as Pathé DTX.138 and Angel 35101

Special thanks to Donald Clarke for the loan of source recording

First reissue since original release

BBC Symphony Orchestra

Jascha Horenstein, conductor

Live broadcast recording, 19th February 1961

"Sunday Symphony Concert", BBC Home Service

BBC Maida Vale Studio 1, London

From the Misha Horenstein collection

First ever release of Horenstein conducting this work

Fanfare Review

Pristine Audio continues to add to the Horenstein discography with this very important release.

Pristine Audio continues to add to the Horenstein discography with this very important release. Metamorphosen was recorded for LP by EMI in 1953, and issued on the Pathé and Angel labels at the time, but has never been reissued in any form, so this is its CD debut. The Symphonia domestica is a BBC broadcast that has never been available, and even more importantly it is the only performance of this work by Horenstein to be issued.

There is a live Metamorphosen from 1964 with the same orchestra, issued by Music & Arts as part of a nine-disc set that I reviewed in Fanfare 28:3, but frankly this studio recording is the more successful reading. Horenstein and the engineers managed a perfect balance between the 23 solo string parts, and Pristine’s XR (ambient stereo) transfer brings out a depth and richness to the sound that was lacking in the original. Horenstein captures perfectly the bittersweet nostalgia and sense of regret, even desolation, that is inherent in this music. With his sparse textures and sensitive phrasing, Horenstein’s performance makes a strong impact.

The Domestic Symphony is not one of Strauss’s most tautly constructed symphonic poems, and it can easily sound disjointed and wander aimlessly. But when well performed it can be one of the composer’s most effective and powerful scores. The source for this release is an off-the-air taping of a BBC broadcast, which suffers from a bit of dropout at the outset but gets better as it goes along, and in the end it makes for acceptable listening for any collector used to the limitations of “historic” recordings. What makes it worth getting used to is that usual combination of Horenstein strengths: rhythmic tautness, careful attention to balance and color, and tempo relationships that seem unerringly right. This latter is not only a matter of actual tempo choices, but also a matter of smooth and perfectly judged transitions. Horenstein projects true and touching sentiment in the love music without turning mawkish,

There is plenty of competition for the Domestica, from historically important recordings by Strauss himself and Furtwängler to fine modern versions by Mehta, Karajan, Reiner, Szell, and Maazel. I will not try to make the case that Horenstein’s is superior to all of them, but I will maintain that anyone interested in the work should hear this recording. Horenstein finds the perfect balance between maintaining structural integrity and giving the appearance of spontaneity, and the BBC Symphony plays as if possessed throughout. At 44:33, this is one of the slower performances in the catalog, but it never feels slow because of the strong rhythmic pulse that underlies even the lyrical sections. Horenstein maintains tension over long spans of generous phrases, and ties everything into a unified whole because he never loses sight of the overall shape. Much gratitude is due Pristine Audio for this immensely gratifying release.

Henry Fogel

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:4 (Mar/Apr 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.

Jascha Horenstein’s name has been one I have known, and he a conductor to conjure with, since autumn 1954. I was 17, entering college, and my world of classical music was expanding rapidly, in multitudes. Through contact with classmates, instructors, in classes, and through a suddenly available expanded base of recordings, I and my peers were inundated; it was a thrilling time. We learned new music, and discovered performers new to us. We were exposed to a broader base of LP recordings, and more easily afforded lower cost labels. Westminster Records sold LPs for $2.99 and so we acquired the recordings of conductor Hermann Scherchen, pianist Paul Badura-Skoda, and many others. From Vox Records came its own stable of soloists, and a conductor named Horenstein.

In those years we were discovering Mahler and Bruckner, and Horenstein recorded both composers (by that time he had three decades’ experience) as well as dynamic Beethoven (the Third and Ninth symphonies stand in memory; I still own the former), and a positively clairvoyant Brahms Third. The orchestras could be ragged—one suspected rehearsals were short and retakes few—but clearly, even to our youthful ears, a master was at work. Comparing Scherchen and Horenstein in Mahler and Beethoven caused many a late-night dormitory discussion, as did analysis of Horenstein’s Bruckner as against the better-recorded, better-played (and more costly) Bruckner recordings of van Beinum and Knappertsbusch on Decca and Philips.

It must have been at the end of 1954 or very early 1955 that I entered our local record shop and saw a new Angel release, with Horenstein conducting two works which, in that day, qualified as exotica: Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms and the Strauss Metamorphosen, both recorded by EMI in Paris in 1953. Angel offered a “thrift pack” for a mere $3.75, so I settled for the new release without notes or the handsome album cover. I have not regretted the purchase these six decades. But I am incredibly grateful for Andrew Rose’s efforts in his remastering of this never first-rate EMI taping. (The Stravinsky has been previously reissued and reviewed in these pages [PASC 418].)

This Metamorphosen, utilizing 23 strings Horenstein selected from the Orchestra de la Radiodifussion Francaise, was not, as Irving Kolodin somewhat waspishly noted in his 1954 Orchestral Music: The Guide to Long Playing Records, “the first (that was contained in a 78 rpm version by Karajan) nor the last word on this subject, but an intermediate one that will pay close attention.” Indeed, not the last, but this listener has been paying close attention for these many years, and can hear the recorded performance now in very decent sonics thanks to Pristine Audio’s issue. The performance is deliberate but does not seem slow except in the concluding section of the work. The opening is gripping and the conductor seems sure of purpose in leading the small band of instrumentalists. Despite having been individually chosen, they are not, truth to tell, the equal in virtuosity to others who have recorded this music, but they are good enough and the performance as a whole has great emotional thrust.

I know I heard the 78-rpm recording to which Kolodin referred in his comments, but all that I recall is how much the side breaks disturbed me in this composition. That, from a teenage ingrate who had reached physical maturity hearing only shellac discs. The greatest impact of this Horenstein recording, 60 years ago, was to be able to hear the composition uninterrupted. In years that followed, I acquired the incredible Furtwängler performance from 1947, almost three and a half minutes faster than Horenstein. Then came Karajan’s remake from the early 1970s, with string playing from his BPO which puts Furtwängler’s violins to shame—or maybe not, since the older performance totally wins points on expression. Add to that another favorite recording, the EMI release by Kempe and the Dresden Staatskapelle, recorded December 1972. Kempe, at a hair over 25 minutes, is two minutes slower than Furtwängler, and about 90 seconds faster than Horenstein. Karajan is yet another minute slower than Horenstein. In this work, tempo relationships are key. It’s not the duration of the performance, but what it tells us.

The same may be said of the massive Symphonia domestica, along with Ein Heldenleben, and the Alpine Symphony, one of Strauss’s three longest orchestral works. This all-knowing college student dismissed the work out of hand, early on. Our college library had a copy of a Vox LP (PL 7220) which purported to be a 1944 Vienna concert performance with the composer leading the Philharmonic. Perhaps; it also may have been a misattributed 1944 performance by Furtwängler. It was a dull-sounding record, and I’m not sure if we ever searched out Decca’s 1952 commercial release with Clemens Krauss leading the VPO in studio conditions (a much praised monaural record, not known to me). In November 1956 Reiner recorded the piece in Chicago and RCA released a dull-sounding monaural LP early the next year. A stereo pressing followed in due course. This was and remains one of the few Reiner discs to which I do not owe life-long devotion. I can’t give a good reason. As was once said to me: Apathy is apathy.

My love affair with the Domestic Symphony began with my discovery of George Szell’s studio recording with his Cleveland Orchestra, recorded on a single day in January 1964, in a Cleveland venue not otherwise identified by Sony. At 41:25, this is probably the fastest performance of the work ever recorded, and to my ear the most persuasive. To hear the first chair players of the great orchestra of that day—Adelstein (trumpet), Sharp (flute), Marcellus (clarinet), Bloom (horn), and Druian still in the concertmaster’s chair—in a work such as this with so many expressive solo “licks,” is an experience to be treasured. At the other timing extreme is Maazel with the VPO in a live performance recording (DG) which takes 44:26. In his comments on the Furtwängler performance of this work the late John Ardoin observes that “the work overstays its welcome and offers several endings, rather than one.” He also comments on the lavishness of the score, and that it at many points reminds one of Rosenkavalier. True, and both of those characteristics come to mind in hearing the Maazel disc. The inflections the VPO brings to the score are unique and may be almost beyond the control or influence of a conductor. I can’t resist.

What of the Horenstein performance? It leans more to the deliberation and lushness of Maazel’s recording than to the clarity and tautness of Szell. What it has in common with Szell (who makes you unaware of the several endings which turn out to be not such), is that Horenstein sees the work straight through. One has the feeling that he knows precisely where this is heading and where it will end. There is control from the podium but not domination. The reins are not taut, but they are never dropped. And, amazingly, this is the most deliberate performance yet, another half minute beyond Maazel. But, it is not slow at all.

The conductor’s cousin, Misha, in a comment reprinted in the notes for this release, observes that it is almost unimaginable what Rose and Pristine Audio have accomplished with the sonics here. The first 10 or so minutes seem a trifle less forward, but otherwise, and ignoring a few instances of drop-out (only one really significant), you forget for long stretches of time you are listening to an off-line broadcast from 1961. The climax of the work comes through with particular brilliance. In an email exchange with the writer, Misha Horenstein also commented that what impresses him is the incredible commitment of the BBC orchestral players. I agree. They are giving their all here, and the edge of the seat concentration is thrilling. How often can they have played this music? Some of them may have been around when Strauss conducted it in London in 1947, a year before his death, but not many, and performances of the piece were not (are not) frequent.

A historical issue need not be “ranked” or evaluated in competition with the currently available crop of commercial issues, but this disc can be placed in context. I continue my loyalty to the Szell and Maazel stereophonic releases of the Domestic Symphony, and to the Furtwängler and Kempe recordings of the Metamorphosen, as well as to the second of Karajan’s three recordings (DG). But I can now hear an old favorite of this threnody for strings in better sonics than I ever imagined possible, and can hear a unique view of the Domestic Symphony, with a great conductor working at white heat and an orchestra inspired to play at the very best—all for the cost of a single disc. Once again, Pristine Audio and Andrew Rose have moved from strength to strength, and deserve our thanks.

James Forrest

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:4 (Mar/Apr 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.