This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

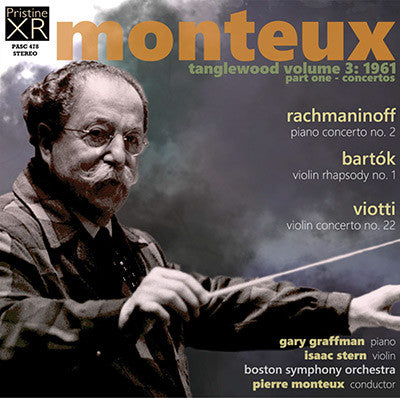

- Cover Art

Monteux's stereo Tanglewood broadcasts part 3: 1961 Concertos

"Feats

of explosive virtuosity appear on both sides of the podium, the solo

and the orchestra in earthy, spirited competition, and everybody wins" -

Audiophile Audition

This third volume of Tanglewood recordings moves us decisively into

the 1960s, with the first of two parts derived from the Tanglewood

concerts that summer. Here we concentrate on concerto works, with one

each from Rachmaninov and Viotti, and a mini near-concerto in Bartók's

two-movement Rhapsody for Violin and Orchestra No. 1, with pianist Gary

Graffman and violinist Isaac Stern.

Whilst both Bartók and

Rachmaninov are of course both household names, Viotti is less

well-known and appears here for the first time on any release on the

Pristine label. Born the year before Mozart, this Italian virtuouso

violinist lived and performed in a number of major European countries

during a perilous time of revolution and war, something that dictated

his movements on more than one occasion.

He is best known today

for his 29 violin concertos, of which the 22nd in A minor played here,

which he wrote in 1792 - the year when revolution forced his relocation

from Paris to London - is the most well-known. Indeed the complete

series of concertos was not to receive its full recording until 2006,

and he would have been almost unknown to the audiences of 1961, save for

an LP of this work recorded in the mid-50s by Isaac Stern with The

Philadelphia Orchestra under Ormandy, one of only two pieces of music by

Viotti available to British LP buyers in the early 1960s. (It is worth

noting Stern returned to Philadelphia in the spring of 1961 to record

his 16th Concerto.)

The two concerts from which these stereo

recordings were taken offer two very different acoustics, for which I

can only blame microphone placement. The piano recording is big, wide

and lush, whilst the violin concert is far more immediate and direct -

in many ways both suit the music perfectly. Sound quality after XR

remastering in both cases is excellent, though a little tape hiss

remains in the violin concert recordings. I have removed a large number

of coughs, most particularly in the superb Rachmaninov.

Andrew Rose

- RACHMANINOV Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18

Gary Graffman piano

Concert of 19 August, 1961 - BARTÓK Rhapsody No. 1 for Violin and Orchestra, Sz. 87

- VIOTTI Violin Concerto No. 22 in A minor

Concert of 23 July, 1961

Isaac Stern, violin

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Pierre Monteux, conductor

Recorded at the Koussevitzky Music Shed, Tanglewood

Audiophile Audition review

The famous last movement combines high-voltage virtuosity and studied arioso, an elastic and compelling realization of a score that can easily become routine.

Every meeting between veteran French conductor Pierre Monteux (1875-1964) and the Boston Symphony Orchestra promised excitement and supple grace, at once. The concerts in the Berkshires allow Monteux access to repertory denied him on commercial records, and so those from 23 July 1961 (Bartok and Viotti) and 19 August 1961 (Rachmaninoff) become especially precious to us who cherish Monteux’s sensitive authority in collaborations. Personally, I await the restoration of the Schumann Concerto that Eugene Istomin shared with Monteux at these concerts.

Gary Graffman (b. 1928) appears in resolute and resonant form in the most popular of the Rachmaninoff concertos, the first movement’s moving with a kind of feline sleekness and accuracy. Prior to this performance, I could not recall having ever heard a note of this composer from Monteux. The grand progression to the tutti statement of the main theme by solo and orchestra enjoys a suave inevitability. Typical of Monteux’s direction, the orchestra’s interior voices add a distinctive color too often sacrificed for the keyboard’s bravura. After the fateful climax, the more lyrical interplay gains a decidedly erotic texture, aided by Graffman’s steely rhythm and even figurations, reminiscent of the kind of mechanical proficiency the late William Kapell could exert. The acoustics of the Koussevitzky Music Shed – courtesy of stereo remastering by Andrew Rose – appear alert and responsive in the Chopinesque Adagio sostenuto as well, in which Graffman and the BSO woodwinds enjoy some liquid ensemble while the strings play pizzicato. The animated sections of the movement retain their arioso and declamatory elements without sag. The famous last movement combines high-voltage virtuosity and studied arioso, an elastic and compelling realization of a score that can easily become routine.

Isaac Stern (1920-2001), while a mighty musician and patron of the arts, remains problematical as a human being, for reasons that can wait for other contexts. His reading of the 1792 Viotti Concerto No. 22 complements his commercial CBS recording with Eugene Ormandy, although Menuhin and Mitropoulos in New York performed a Kreisler arrangement of the work in 1951. Stern had not commercially recorded the Bartok 1928 First Rhapsody (written for Joseph Szigeti), composed in the czardas style Liszt invented. Again, Bartok’s music does not fit within the official Monteux discography. Stern and Monteux infuse the drone-like Lassu section with ripe, Hungarian, lyric melancholy. The scale pattern of the Lassu will return at the conclusion of the Friss section, but not before a procession of dance tunes, the first of which strongly resembles “Simple Gifts” from Copland ensues. The BSO manages to invoke the cimbalom successfully to add to the gypsy effect. Feats of explosive virtuosity appear on both sides of the podium, the solo and the orchestra in earthy, spirited competition, and everybody wins.

The Viotti Concerto might qualify as “Italian galant” in style, although in its more energetic, martial moments it certainly anticipates much of Paganini. Stern and Monteux play a relatively uncut edition. In his days when he maintained practice, Isaac Stern sported a sweetly burnished tone, captivating as it could be boldly and accurately piercing. The microphone placement appears close up to Stern’s instrument, which cannot always subdue the audience’s contribution to auditioning for Violetta in La Traviata: if only they’d cough on the beat! The virtuosic passages call mostly for double-stopping and quick alternations of tempo, with an occasional foray into harmonics. The cadenza proves rather brief but pungent as Stern delivers it.

The sweet secondary melody has much in common with the equally compelling melody of the Adagio, which Stern and Monteux milk for easy and memorable listening. Fritz Kreisler recorded the last two movements via a radio broadcast in the 1940s, and the Adagio made his cup of tea, also. The progression of half steps – rather anticipating moments in the Beethoven Concerto – becomes ardent and mesmerizing, bel canto for the violin. Though brief, the second movement cadenza reminds us that Stern could beguile us. The last movement, Agitato assai, means to be a showstopper. The driving motif – with its flute response – caught my ear when I first heard it when a youngster. The easy fascination of this charming piece caught the attention of Brahms, who mentions his pleasure in the work in a letter to Joachim. Those two masters might well have savored the performance Pristine has restored to us in effective sound.

—Gary Lemco

Audiophile Audition