This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Sleevenotes

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Reviews

In November 1922, while still a student, Jascha Horenstein made his professional debut conducting Mahler's then still controversial First Symphony with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. The event took place in the Musikvereinsaal “where Mahler used to give his concerts”, as he was fond of reminding his interlocutors. In the Neue Freie Presse, Vienna’s most prestigious newspaper, Horenstein was perceived as “toiling mightily with his interpretation”, and was characterized as “without question a fanatic, obsessed by Mahler´s music and by his own mission.” The words 'fanatic' and 'obsessed' were used commonly by reviewers of his concerts during the Weimar era.

In the years following his Vienna debut, Mahler's First became something of a musical calling card for Horenstein, including for his first appearance with the Berlin Philharmonic in October 1926, a concert attended by Berthold Goldschmidt who described the performance as “fiery and fanatical, full of dynamic exaggerations, but with a clear profile”. Horenstein also chose the symphony for his debut in Frankfurt less than a year later where, according to Adorno, he was favorably compared to the young Mahler by some who had seen and heard the Bohemian composer in action. Thereafter Horenstein conducted the work at least two dozen times in different places before making the present recording of the symphony for Vox Records in Vienna in February 1953.

The first reviews were not encouraging. In May 1953 Harold C. Schonberg in the New York Times thought that “Horenstein toys around with the music too much. He tends toward sentimentality; he underlines phrases that need no underlining, and there is a consequent lack of subtlety”, while in the UK the influential Gramophone magazine ended its review by suggesting that owners of a rival version need not bother adding Horenstein's recording to their collections!

History has not validated those early reviews and for the next twenty years Horenstein's Mahler First, owing to his unusually lucid grasp of its complexities, became the recording against which all the others were measured, until he re-recorded it in stereo. Its great warmth and spontaneity, executed in a style that would have been familiar to the audiences of Mahler's time, and Horenstein's complete engagement and identification with Mahler's idiom, account for its appeal, despite the inferior recorded sound and some less than stellar orchestral execution. Horenstein's interpretation, quite unlike anyone else's, is notable for its clear textures, his carefully balanced buildup and release of tension in the first and last movements, for the rustic exuberance of the scherzo, and for the alluring blend of poignancy, parody and sentimentality, with its judicious and tasteful use of portamento, in both the first and third movements. In the finale, the strength and weight of powerfully controlled climaxes in the turbulent sections are offset and complemented by a charm and elegance in the lyrical moments that underline its authentic, old-world, Viennese character. Often hailed as one of the handful of great interpretations of this work, Horenstein's carefully measured, lovingly shaped reading continues to attract admirers more than sixty years after its first appearance on disc.

Misha Horenstein

MAHLER Symphony No. 1 in D major

1. 1st mvt. - Langsam, schleppend - Immer sehr gemächlich (16:52)

2. 2nd mvt. - Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell, Recht gemächlich (8:20)

3. 3rd mvt. - Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen (11:40)

4. 4th mvt. - Stürmisch bewegt – Energisch (20:51)

Vienna Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Jascha Horenstein

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

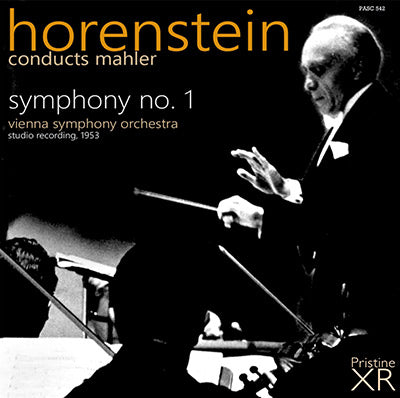

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Jascha Horenstein

Recorded in Vienna, February 1953

First issued on Vox PL8050, July 1954

Total duration: 57:43

M.M., The Gramophone, July 1954

To suggest that any performance of Mahler is perfect is to court the wrath of the Mahler enthusiast almost as surely as to suggest that any of the master's works is itself in any way less than perfect. There is, actually, no temptation to suggest that this performance is perfect; but it does seem to me to be highly idiomatic. Clearly an enormous amount of care on Horenstein's part has gone into it, and everything is shaped with an eye to effect; the glissandos gliss with a vengeance, the parodistic sections are very conscious of being superior to the music parodied. If a listener remains unconvinced it will be because he considers these sections to be, in any case, at the feeblest level of the symphony, and their emphatic presentation to be a series of spotlights on the shabbiest part of its fabric.

In the outer movements admiration is less encumbered with misgivings. Horenstein often, throughout, stops short of achieving a perfect ensemble especially with the horns, who are at times erratic. At the orchestral level, I prefer the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra under William Steinberg on Capitol CTL7042 (April, 1954); and I also prefer the American version interpretatively but such an opinion is even more so than usually a personal one, and not at all necessarily likely to be shared by every listener.

Capitol offered a very good recording, and if the Vox had been equally good a choice between the versions would not have been easily made. But although the new disc is entirely presentable - greatly superior for example, to the Columbia version of the work - it falls short, technically, of the Capitol here and there, and suggests no necessity for any owner of that record to consider making a change.

R.L., The Gramophone, April 1971

This record originates from the early 1950s and held its own in the catalogue for many years. It still strikes me as a performance of great warmth and has more spontaneity, I think, than Horenstein's recent version with the LSO, admirable though that is in so many respects. Admittedly the orchestral playing is not always impeccable and the balance places the woodwind a little too far forward so that ppp markings do not register as such. The actual quality of the recorded sound calls for a good deal of tolerance and I would hesitate to recommend this to anyone who sets store by vividness of sound and detail. At the same time I must confess that despite the poor recording I have derived more pleasure from listening to this warm-hearted and well-judged reading than I have from many of the more recent versions. Bruno Walter's CBS Classics recording is probably the safest bargain recommendation but echt-Mahlerians will, as I have suggested, find that this reissue has many musical rewards.

Richard Osborne, Records & Recordings, April 1971

This 1954 performance of the First Symphony strikes me as being very fine. The recording, apart from some damping down in the big climaxes, is perfectly good, the orchestral playing very firm, very characteristic. It is not a 'modern' sounding recording, of course: there are no shimmering perspectives at the start of the symphony. The clarinet fanfares sound very immediate, the horns are rather fulsome, just as later, at the start of the third movement, the timpani line is unashamedly 'there'.

Yet if there is immediacy in the recording (and where it is well defined, this is all gain) there is also a great deal of immediacy in the playing; at the start of the finale, for instance, where Horenstein generates sufficient tension to enable him to set up counter-tensions, allowing the music to drive forward, yet insisting on the great downward thrusts of sound, holding the lightning flashes in a proper rhythmic perspective. This is one point where he scores over Bruno Walter on CBS Classics - Walter reining the music too tightly at the start of the movement, giving it a comparatively sedate forward motion. Such is Horenstein's grasp of the structure of this movement that one can readily accept his very 'maestoso' treatment of the very end, something very much in line with his passionate but dedicated response to the music as a whole.

The thing about the playing is that there is never anything glib about it; the oboe's wonderfully intense phrasing at Fig 42 of the last movement creating considerable emotional tension at a crucial point of transition is a small, but very typical, example of the control Horenstein seems to exert over the orchestra at every point. And this is as true of the first movement as of the last (first movement repeat carefully observed). I like, too, the funeral march, sombre, laden with menace but with a kind of muted nostalgia about the Lindenbaum theme - Horenstein, like Walter, very much 'inside' the idiom at this point - and the Ländler which drags along in exactly the right way, the pulse strong, the textures firm, the rhythms strong and chunky.

In fact the performance as a whole commends itself. Like the Kubelik on Decca's Eclipse label and the Walter, it is certainly echt-Mahler. Not as 'finely' played or as brilliantly recorded as the later Horenstein/Unicorn issue, of course, but well worth investigating if economy is the principal factor.

Henry Fogel, rec.music.classical, 24 November 1994

I am not embarrassed by attribution of a rave for Horenstein's Vox recording... there is surely no question in my mind that it is one of the handful of great interpretations of this piece on disc.