This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

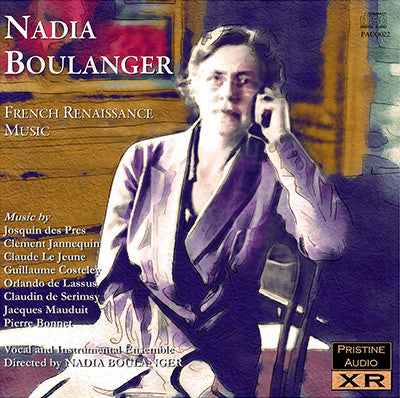

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

Nadia Boulanger's French Renaissance Vocal Music

Extraordinarily rare 1950 album of superb early music from France

I have in my possession a most fabulous treasure, Andrew, an extraordinarily rare album of French Renaissance Vocal Music released on American Decca in 1950 by Nadia Boulanger. The performances as such are easily as good, if not better, than the famous Monteverdi album. and - wonder of wonders! - the liner notes are by Boulanger herself. If you would be interested in restoring this lost gem (and believe me, she made so few recordings I think it would sell like hotcakes), I would be most happy to send it to you. Just let me know.... - LB

I had been in correspondence with Lynn Bayley with regard to the recordings of Toscanini, about whom she is a renowned expert, when this paragraph slipped into an e-mail. Naturally I jumped at the opportunity, and a few days later a well-transcribed copy landed on my desk, ready for restoration.

It quickly became apparent that Decca's release was in fact a compilation of recordings, some of which would have been cut to disc for 78rpm release, others recorded (probably) directly onto tape. Thus there is a degree of inconsistency between some of the songs, sound-wise. I've tried to compensate for this wherever possible, though not at the expense of reducing the quality of any of the finer-sounding recordings.

As with Boulanger's much-treasured Monteverdi recordings of 1937, this is a pretty-much unique document of this particular series of, in this case, French vocal music of the era. Thanks to its LP provenance the sound quality is much improved - and the inimitable style and standard of performance remains superlative.

Andrew Rose

- Mille regretz (Josquin des Pres)

- Ce moys de may (Clement Jannequin)

- Helas, mon Dieu (Psalm from "Second livre des Meslanges") (Claude Le Jeune)

- Bon jour, mon coeur (from "Meslanges") (Orlando de Lassus)

- Noblesse git au coeur ("Musique 1570") (Guillaume Costeley)

- Quand mon mary vient de dehors (Orlando de Lassus)

- A declarer mon affection ("31 Chansons Musicales") (anonymous)

- Mignonne, allons voir si la Rose ("Musique 1570") (Guillaume Costeley)

- Hau, hau, hau le boys! ("31 Chansons Musicales") (Claudin de Serimsy)

- Revecy venire du Printemps ("Le Printemps," 1513) (Claude Le Jeune)

- Vous me tuez si doucement ("Chansonettes Mesurees") (Jacques Mauduit)

- Tu ne l'enten pas, c'est latin (Claude Le Jeune)

- Au joly boys ("31 Chansons Musicales") (Claudin de Sermisy)

- Francion vint l'autre jour (Pierre Bonnet)

- Le Chant des Oyseaux (Clement Jannequin)

(N.B. Many of these spellings are in Old French, and differ from their modern counterparts.)

Released in the US in 1950 as Decca LP DL 9629

Transfer by Lynn Bayley from her private collection

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, December 2007

Duration 42:20

French Renaissance Vocal Music

notes by Nadia Boulanger

Introduction

Every work of art is a triumph of technique. From a certain happy arrangement of words, lines, colors, or sounds, beauty is suddenly born. How? It would be very difficult to say, for the essence escapes analysis. The masters of the Renaissance, admirable artisans that they were, knew this well. To be sure, always having taken pains to do a good job wherever the responsibility and the dignity of the artist were concerned, they put themselves in the hands of the gods when it came to going beyond the limits where human control ends.

Even at the risk of offending some people, it is fair to assume that emotion is not the fruit of idle sentimentality but of a complete command of means. “Whoever wants to write down his dream owes it to himself to be infinitely awake” (Paul Valery). It is certain that "this secret and almost incredible power of moving hearts in one way or another," as Calvin put it, results from the very nature of the form, of melodic curve, rhythmic life, lengthening and contracting of cadences, relation of intervals, both melodic and harmonic – in short, of the thousand and one elements of which music is made.

This is not the place to undertake a detailed study of

these elements. The object of this short introduction is simply to

invite the listener to take advantage of the joys that can be brought to

him by the treasure of an art as much alive today as ever. In the

preface to the first volume of his admirable collection, Maitres musiciens de la Renaissance Française, Henry Expert says: "It is a question of rescuing the music of a great century from

the oblivion in which until recently its poetry was still slumbering;

and, while enriching the history of art, of uncovering an unexplored

comer of the French spirit." This record has been planned to

highlight some representative types of this music and make a sort of

synthesis of them. A few remarks to point out the outstanding

characteristics of each piece will therefore be in order.

Closely allied to poetry and composed almost entirely for vocal ensemble, situated in time at the boundaries of modality and tonality, counterpoint and harmony, written by men who belonged to both church and court and who were deeply influenced by the Reformation and in a different sense by the rediscovered ancients, "the musical art of the 16th century is the reflection of the mind, life, and morals of this age when social and religious institutions as well as artistic and literary traditions were clashing in a passionate conflict, when character soared, unfolding the inmost qualities of our race." (Henry Expert)

1. Mille regretz

(Josquin des Pres, 1450-1521)

A priceless piece, very pure example of the mode of E transposed to F sharp. Notice the still predominant role of the tenor and the extremely subtle contrapuntal details. Nevertheless, the overall effect is one of extreme simplicity.

A thousand regrets that I must leave you. My heart is so full of mourning and sorrow that my days will soon come to their end.

2. Ce moys de may

(Clement Jannequin, 1493-1560?) "31 Chansons musicales" (Attaignant, 1529)

This little song, bright and fresh, is written in major on a double-iambic rhythmical pattern starting on the upbeat. At times the rhythm is reversed, and this slight modification produces a great effect. Notice also the three-voice passages, the imitation between the soprano and the tenor, and the varied resting places of the melody.

Early one morning this beautiful month of May, I'll don my green frock and skip forth to win my lover's embrace.

3. Hélas, mon Dieu

(Claude Le Jeune, 1528-1600) Psalm from the "Second livre des Meslanges," 1612 (Posthumous work)

Henry Expert says: "This psalm is certainly one of the boldest, the most innovational, and also the most moving works of our music of the Renaissance: such a page honors a great artist."

The voices are here doubled by the instruments, as was rather usual. "It should be noted that during the 16th century the customary practice was to accompany the vocal concert with whatever instruments were available," writes Henry. Expert. The striking effect produced by this great piece depends on the overlapping entries of the chromatic, descending motive with its succession of major and minor thirds, a superb instance of the mislabeled “false relation.” Notice also the alteration of slow dactyIs, doubly fast iambs, and anapests; the "polyrhythmic" intricate contrapuntal imitations; the plain syllabic periods; the restatement of the solemn exposition; and the final broad plagal cadence.

Alas, my God, thy wrath is turned against thy servant. Terror fills my heart, Virtue is gone from me. I cry unto Thee and seek Thee everywhere. Oh God, forsake me not!

4. Bonjour, mon coeur

(Orlando de Lassus, 1532-1594) “Meslanges” (1576)

Every note in this peerless piece deserves attention.

The rhythmic pattern of the poetry (verses of 10 feet—4 + 6—followed by.

verses of 7 feet), the alternation of dark and light syllables, the

repetition and displacement of the words "Bon jour "—all these spur

Orlando de Lassus to discoveries of the rarest and most delicate

sensitivity. The movement from modality to tonality in each phrase gives

the cadences a flavor of surprise,

which is heightened by the way they are introduced.

We know that Ronsard sang his verses when he composed them, as he himself says. The first edition of the “Amours” was accompanied by 32 sheets of “airs notes” by various composers. "Without music," stated Ronsard, "poetry is almost graceless, just as music without the melody of verses is inanimate and lifeless."

Good day, my sweetheart, my pretty one, my dear love, my gentle dove. Good day, my sweet rebel.

5. Noblesse git au coeur

(Guillaume Costeley, 1531-1606) "Musique 1570"

Here Guillaume Costeley appears in an unfamiliar light. Charming and sprightly poet though he was, he had also his vein of austerity and depth. The passage from major to minor that results from a chromatic movement in "Helas, mon Dieu" occurs here between two voices. "False relation," say the theorists, but composers seem to have cared not the slightest about this condemnation. Notice the ornaments that break the severity of the syllabic ensemble, the contrapuntal passages that animate it, and the syncopated imitations motivated by the words "se lier à lui."

Nobleness dwells in the heart of the virtuous man. Like fructuous trees, he brings forth good fruit in due season. Evil vanishes before him, and fear melts in his presence as wax before fire. Is not this what it means to live in nobleness? Is it not to such a man that one should bind oneself?

6. Quand mon mary vient de dehors

(Orlando de Lassus)

Here Orlando de Lassus paints a canvas à la Breughel, bright in color, extraordinarily alive and gay, even Rabelaisian.

Ingenious musical artifices give this piece its vivacity: the dialogue at the beginning, the coming together of the two tonics G and D, the sudden entry of the four voices, and certain rhythmic juxtapositions.

Whenever my husband comes home, it is my fate to be beaten. He is a jealous villain. I am young and he is old.

7. A déclarer mon affection

(Anonymous) "31 Chansons Musicales" (Attaignant, 1529)

This venerable modal piece, with its alteration of B flat and B natural, shows sobriety and intensity, brevity and grandeur, going hand in hand.

After a slowly repeated chord (dactyl), the melody moves calmly in stepwise motion, stops on D, and then twists insistently around it. At the end of the piece this effect is made even more impressive by repetition and the imitative twining of the bass. Notice the eloquence of the bass's second phrase and later on the symmetrical ascent of the tenor (predominant throughout the whole work) that prepares the way for the expansion of the soprano.

The low range, the almost constantly continuous movement of the voices, the rhythmic severity—all contribute a sort of lively immobility to this admirable composition.

To declare my affection, my writing, which is full of passion, is enough. Whoever cannot regain this good, which all others surpasses, puts his hope in the Psalter, being sure of grace.

8. Mignonne, allon voir si la Rose

(Guillaume Costeley) “Musique 1570" Poem by Pierre de Ronsard

This is an exquisite and celebrated piece. The poem

sings in every memory, the music is familiar to many; yet both sound

ever new. Two elements follow each other. In the first (A), which is

contrapuntal, and three-part without bass, the voices imitate each

other, join together again (notice the point where all three are a

second apart—G, .A, B flat), then separate anew. In the second (B),

which is purely syllabic, they form little harmonic

blocks, absolutely simultaneously: A+A+B+B+A+B+B.

This seems a dry way to summarize this little masterpiece, but where is the point in trying to describe what it demonstrates so clearly by itself?

Sweet love, let us see if the rose, which opened its crimson petals to the morning sun, has not this evening lost its bloom. Waste not your youth, for age will fade your beauty as the sun the rose.

9. Hau. hau, hau le boys!

(Claudin de Sermisy, 1490-1562) "31 Chansons musicales" (Attaignant, 1629)

One must not be misled: this robust, somewhat heavy drinking-song is not so simple as might be thought at first. Listen well and you will soon perceive the richness of its rhythmic combinations (binary and ternary), of its vocal grouping (massive blocks of the four voices, separated by entries bursting forth from all sides), and of its bright, open, perfect consonances.

Let us take this opportunity to invite attention to what we might dare to call the "entry'" of the rests. A rest is more often the beginning of silence than merely the end of sound. It frequently has still another usage. For instance, if in a perfect triad the root is supplanted by a rest, the third tends to become a new root; if the fifth is supplanted by a rest, the root may become a new third. This elementary statement of the principle is one thing: the way it has been put into practice is another. One of the examples this piece offers of its use occurs immediately after the words "ie mv en vois" are heard in the men's voices. Once one has noticed how this process works, one will be struck by the abundance of examples to be found in virtually all subsequent music.

Hau, halt, hau Ie boys! Let us pray God to guard this "gentle" wine of France. Let's drink six draughts, not only three, to clear our throats and sweeten our voices. The more we drink, the merrier we. Hau, halt, hau le boys!

10. Revecy venir du Printans

(Claude Le Jeune) "Le Printemps," 1513 (Posthumous work in "Vers mesurès a l'antique")

Here is one of the most characteristic pieces the Renaissance has left us, with its masterly writing and remarkable rhythm and form.

All the verses except one are based on uu—u -u … that is, two shorts, a long and a short, a long and a short, and two longs. The ornaments that Mersenne calls crispaturae vocum ("vocal curls") represent here and there the small change. This work is composed of two elements: the rechant and the chant (refrain and strophe). The rechant is syllabic and in 5 voices (notice the vocalize of the tenor that adorns it): it is repeated without change, but the chant is exposed in varying versions, first by 2, then by 3, by 4, and finally by 5 voices. And so we have: R+A’+R+A”+R+ A’’’+R+A’’’’+R+R.

Neither the listener’s ear nor his mind will fail to appreciate the masterly, exquisite way in which Claude Le Jeune has responded to the challenge of this form.

Spring is here again, the beautiful season of love. Waters run clear, the sea calms its angry waves. The duck joyfully plunges into the pool. The sun shines more brightly, dispersing clouds and shadows. Cupid shoots his amours far and wide, and all nature rejoices. Let us, too, laugh and be merry to celebrate this gay season.

11. Vous me tuez si doucement

(Jacques Mauduit, 1557-1627) "Chansonnettes mesurèes" by Jan-Antoine de Baif.

It is well known what part Jacques Mauduit took in the work of the Académie du Palais, originally Academie de poesie et de musique, and at that time protected by Charles IX because its "associates worked to revive both the way of writing poetry and the measure and order of music used in ancient times by the Greeks and the Romans."

Mauduit collaborated with J. A. de Baif, setting to music some of his psalms in measured verse and, according to Mersenne, wrote treatises on rhythm and on "the manner of making measured verses of all kinds in our language to give a special force and energy to the melody." The "chansonnettes mesurées" of J. A. de Baif inspired Mauduit to compose in the tenderest vein. In "Vous me tuez," the charm of the melody is emphasized by the elegant writing of the other parts, and the suppleness of the rhythm holds the attention Here again, it is thanks to technical means that the poetic emotion is engendered.

You kill me so gently that I know nothing sweeter than such a death. I am so happy to be in love that I welcome the anguish. I seek nothing sweeter than to die thus. If we must die, let’s die of love.

12. Tu ne l'enten pas, c'est latin

(Claude Le Jeune)

How happy the age when the music for both light-hearted amusements and the most solemn ceremonies was composed by the same masters, when the essential principles were so solid that laughter could burst forth with the utmost freedom, and when a Claude Le Jeune, having written the admirable and severe “Hélas, mon Dieu” and the charming “Revecy venire du Printans,” needed to have no qualms about amusing himself with writing “Tu ne l'enten pas.”

The Gallic spirit is unrestrained here, but far from encouraging Claude Le Jeune to be easygoing and careless, the vivacity of the subject impels him to sharpen his tools still more and to multiply his technical discoveries. Everything had to be suggested, everythingimplied, dared but not abused.

The licentious import of “Tu ne l'enten pas, c'est

latin” is underlined by the “la, la, la,” full of double-entendres,

which leave the meaning in suspense. So much granted, the tale is

completely free to venture even beyond the limits of decency, for “You

don't understand, it's Latin.” Behold, our author launched headlong into

his spicy story! He plays with unbelievable skill on his “Tu ne I'enten

pas,” which takes on every possible shade of

meaning. Examine it

closely and you will see how skillfully Claude Le Jeune has handled all

these details: imitations, canons, inexhaustible rhythmical combinations

that, by the way, make performing this work a very perilous venture.

You don't understand, it’s Latin. A farmer’s daughter got up one morning, took three measures of barley, and went straight to the mill. "My friend," said she, "will my grain be well ground?" “Yes, my beauty,” said he, “just wait till tomorrow and see.” "My trouble’s all for nothing: you're only a wanton wastrel." You don't understand, it's Latin!

13. Au joly boys

(Claudin de Sermisy) "31 Chansons musicales" (Attaignant, 1529)

How well ordered is everything in this mournful little piece, the expressiveness of which is, in the end, its most striking feature. Again and again it must be repeated: it is on the choice and organization of means that the final effect invariably depends. To rely only on emotion generally results in disorder. Here, on the contrary, everything bears and invites scrutiny.

Under repeated chords in dactylic rhythm, the bass

exposes the melodic pattern which will be expanded in the tenor at the

words “En ung jardin” and heard in canon later on. Notice the parallel

movements at “en l’ombre d’ung soucy,” the eloquence of the repeated

high note at “En ung jardin,” and the symmetrical descent of the four

voices. All the ornaments have disappeared: nothing remains but the

unadorned dactylic rhythm (cf. “Death

and the Maiden” of Schubert,

the “Allegretto” of the Seventh Symphony of Beethoven, the end of

Stravinsky’s Orpheus). Admirable music, in truth.

In the lowly woods I must go and strive to overcome my sorrow. I have lost my love. Time is heavy on my hands. Solace, you have no more power over me.

14. Francion vint l’autre jour

(Pierre Bonnet, 15?-16?)

This charming love ditty is a good example of the polyphonic chanson in the process of becoming the court air for one voice. The four voices that accompany the soprano have only a secondary role, rather harmonic. Notice, however, the writing for the tenor in the third verse, the play of minor and major thirds, and the change in sonority when the bass becomes silent.

Francion came to see me the other day and spoke of love so delicately that never shall care for anyone but him. “Kiss me, my sweet,” said he. “Why deny me what so freely you give to others?” “No, no,” said I angrily. “If I did, you would soon tire of me.”

15. Le Chant des Oyseaux

(Clement Jannequin) “Chansons” (1529)

“Awake, slumbering hearts. The God of Love summons you,” sing the voices one after another. The music of this poetical, ravishing refrain will be heard 5 times, separated by 4 couplets. The first one starts with: “On this first day of May, birds do wonderful things. Hark to their song,” and the bird concert begins. Light, onomatopoeic sounds break forth on all sides. They imitate and answer each other, some chirping, others skipping about, still others moving more slowly, and again comes the refrain: "You will all be filled with joy, for the season is a good one."

"You will hear soft music from the throat of King Thrush," continues the second couplet, and the concert begins anew. "Ti, ti, ti, piti, chouty, thouy," warble the birds in a little dialogue bouncing back and forth, introducing an increase in rhythmical liveliness and an astonishing variety of timbres. What flashing, amusing, evocative invention! New motives appear endlessly, taken up by voice after voice in an unbelievable accumulation, interrupted by the refrain: "To laugh and enjoy life is my motto. Let everyone join in."

"Nightingale of the lovely wood sings sweetly to banish your care," goes the next couplet, and our little singing friends trill and twitter: "Frian, frian, frian, frian. Tar, tar, tar. Velecy, velecy, tu, tu, rrr." Their songs grow brighter and brighter, more and more involved, endlessly varied. "Flyaway, regrets, tears, and cares, for the season demands it," runs the refrain, but the couplet shouts roughly, "Away with you, Master Cuckoo, begone,

for you are nothing but a traitor."

"Cuckoo, cuckoo, cuckoo," they repeat and repeat, slowly, quickly, high up, low down, until they burst out with: "By treachery in others’ nests you lay your eggs." All the birds have now brought the concert to its climax— blackbird, cuckoo, starling, nightingale, chaffinch, golden oriole—and once more they warble sweetly, "Awake, slumbering hearts. The God of Love summons you." And so ends this thrilling piece, one of the best of all chansons descriptives.