This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Press Review

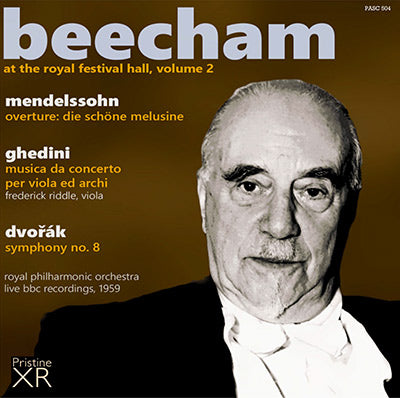

This is the second of three volumes dedicated to the two concerts given on 25 October and 8 November 1959 by Sir Thomas Beecham and his Royal Philharmonic Orchestra at London's Royal Festival Hall and captured in excellent mono by the BBC Transcription Service. Whilst these recordings preserved the main body of both concerts, it would appear that only the encores from the second concert have survived, which alas deprives us of the opportunity to hear Beecham's Delius one more time. Whilst some of these recordings have been previously issued on the BBC Legends label, the sound quality heard on the present releases is considerably improved thanks in no small part to XR remastering. Here the orchestral timbre is much more realistic, the hard, harsh edges of the original recordings have been softened, and a rich body of sound restored. Our series also includes recordings never previously issued. I have elected to remove the announcements dubbed on by the BBC for later rebroadcast. The length of both concerts has required a certain amount of juggling in order to fit three single-CD volumes.

Andrew Rose

1 MENDELSSOHN Ouvertüre zum Märchen von der schönen Melusine, Op. 32 (10:50)

2 GHEDINI Musica da Concerto per Viola ed Archi (1953) (23:37)

Frederick Riddle viola

DVOŘÁK Symphony No. 8 in G major, Op. 88

3 1st mvt. - Allegro con brio (9:59)

4 2nd mvt. - Adagio (10:42)

5 3rd mvt. - Allegretto grazioso - Molto vivace (6:55)

6 4th mvt. - Allegro ma non troppo (8:40)

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Sir Thomas Beecham

Dvořák

Recorded 25 October 1959

Mendelssohn & Ghedini

Recorded 8 November 1959

Recorded at the Royal Festival Hall

London by BBC Transcription Services

Total duration: 70:43

Beecham, the beneficent host at the feast

By Neville Cardus

The Guardian, October 27, 1959

SIR THOMAS BEECHAM returned to London’s routine concert scene on Sunday night, and the crowded audience in the Festival Hall, falling at once under the old spell, was rejuvenated into a fresh awareness of unburdened musical delight. At the end of the programme, hardly anybody in the audience got up from his or her seat or showed the slightest intention of going home. Even the critics stayed on—and no conductor, no musician, alive or dead, has received a rarer tribute than that.

Sir Thomas spoke to us, saying, “I suppose you are all waiting for an encore?” In a single voice the packed multitude roared “Yes!” and then Sir Thomas said, “This is a matter requiring some thought. I know only a few pieces."

One of his secrets is that he draws the audience into his circle. Other great conductors work on another dimension, so to say, withdrawn to a level to which we dare not approach intimately. Sir Thomas is the beneficent host at a feast to which we have been invited. He is the connoisseur. Moreover, during this present age, in which music every day seems more and more in danger of becoming an austere science, or one of the many means of disseminating education and culture, he reminds us that the art originally was designed to give pleasure to civilised men and women. Sunday's audience went home happy. Seldom have I seen so many English people leaving a concert hall as happy.

Sir Thomas presented a programme which with other conductors might not have been free of tedious moments. The “Clock” symphony of Haydn was followed by Lalo's G minor symphony, a work hardly consistently engrossing, though not without agreeable periods linking it to Chausson (who also wrote a symphony now sadly neglected here). Next we heard the G major Symphony of Dvorak. Sir Thomas found the right approach to each of these pieces from its first phrases, and though every bar was suffused by his own personality, Beechamised unmistakably, yet each composer spoke, or rather sang, in his own voice.

Even Sir Thomas's manner, his movements, changed as he modulated from Haydn to Lalo. In the Haydn symphony he bent down, stroking the music affectionately. For Lalo he became physically more upright and rhetorical. For an octogenarian he was wonderfully animated and active. No conductor equals him in the way he curves a melody, floats in on the orchestra’s surface, passes it on to another instrumental group, all the time keeping the rhythm fluid and unbroken. The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra plays constantly and always admirably in the Festival Hall; but under Sir Thomas it is enriched by a more luminous, more rounded texture which loses nothing, but gains, in distinction of inner parts.

The Dvorak symphony was unfolded in all its charming variety; pastoral poetry mingled with tones evoking legend and history, the wood-wind bubbled with the joy of playing. Here, perhaps, lies the essential Beecham secret—his baton calls up the spirit of delight and it is answered freely and generously. It is a fascinating prospect that within the next twenty-four hours or so, the Festival Hall will have heard music conducted by Sir Thomas and by Klemperer—two artists worlds apart. Compared with the difference, and temperamental distances between them, the North and South Poles are next door neighbours. But what a proof we have in Sir Thomas and Klemperer of the rich musical climate which nurtured them. As an encore Sir Thomas conducted an unfamiliar piece by Delius—“ Sleigh Bells." Why does he not give us much more of Delius nowadays?