This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Full Track Listing

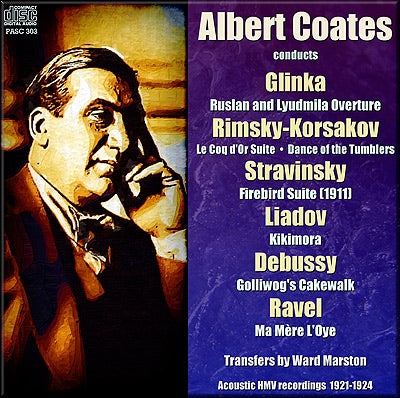

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

Recorded 5 May 1922; Matrix Cc1292-2; Issued on HMV D658.

Recorded 10 May and 14 July 1922.

Issued on HMV D732-734.

Side 1 recorded 14 July 1922; matrix Cc1307-4; HMV D732.

Side 2 recorded 10 May 1922; matrix Cc1308-2; HMV D732.

Side 3 recorded 10 May 1922; matrix Cc1309-2; HMV D733.

Side 4 recorded 14 July 1922; matrix Cc1310-4; HMV D733.

Side 5 recorded 14 July 1922; matrix Cc1659-1; HMV D734.

Side 6 recorded 14 July 1922; matrix Cc1660-3; HMV D734.

Recorded 14 July 1922; matrix Cc1661-1; HMV D658.

Recorded 24 and 29 October 1924. Issued on HMV D958 and 959.

Side 1: 1. Introduction – Kashchei's Enchanted Garden – Dance of the Firebird

recorded 29 October 1924; matrix Cc5298-1; HMV 958

Side 2: 2. Supplication Of The Firebird

recorded 29 October 1924; matrix Cc5297-2; HMV D958.

Side 3: 3. The Princesses' Game With The Golden Apples; 4. The Princesses’ Khorovod

recorded 24 October 1924; matrix Cc5291-1; HMV D959.

Side 4: 5. Infernal Dance Of All Kashchei's Subjects

recorded 29 October 1924; matrix Cc5296-2; HMV D959.

Recorded 28 October 1921; matrix Cc608-2; HMV D620

Recorded 25 April 1922; matrix Cc1243-2; HMV D620.

Recorded 25 November 1921, and 25 April 1922. Issued on HMV D708 and 709.

Side 1, Pavane de la Belle au Bois Dormant; Petit Poucet.

recorded 25 November 1921; matrix Cc709-2; HMV D708.

Side 2, Laideronette, Impératrice des Pagodes.

recorded 25 November 1921; matrix Cc710-3; HMV D708.

Side 3, Les entretiens; De la Belle et de la Bête.

recorded 25 April 1922; matrix Cc1241-3; HMV D709.

Side 4, Le Jardin Férique.

recorded 25 April 1922; matrix Cc1242-2; HMV D709.

London Symphony Orchestra

Albert Coates, conductor

Acoustic HMV recordings 1921-24

Transfers by Ward Marston

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Albert Coates

Total duration: 70:19

Review of this Firebird Suite recording, 1925:

"I can imagine strife in many a peaceful home when Part 4 of this suite is reached.

Father: "I call that a noise."

Son or Daughter,

with that desire to irritate so conspicuous in happy families : "Noise?

A term used by the Elizabethans to denote a band or company of

musicians."

(Confused sounds from father.)

Mother, reading newspaper, quite irrelevantly remarks "How terrible these Bolshevists are."

Son,

of course, misunderstands, and replies with withering scorn "Naturally

you cannot understand that the juxtaposition of tonal masses, the

empirical atonalities, etc., etc." (until the entire family is flattened

out!)

The Firebird music suffers more from being detached from

its proper setting—the theatre—than did the later work Petrouchka. It

will sound extraordinarily scrappy and disjointed to anyone who has not

seen the ballet. Moreover, the titles affixed to the records do not

correspond very satisfactorily with the plot given in the supplement.

Further, Mr. Percy Scholes' excellent analytical notes, done for a

B.B.C. concert at Covent Garden, from which I have culled some

information, present the music in a different sequence to that given

here. Perhaps, therefore, the following analysis, merely a personal

interpretation fused with the main outlines of the story, will be

helpful.

Part 1.—An enchanted garden with something

sinister and evil lurking in the background. A scene bathed in

half-light. After many obscure mutterings the air suddenly grows

tremulous with sound, a rich glow dispels the shadows. The wonderful

exotic fire bird flutters into the garden.

Part 2.—She

dances round a silver tree loaded with golden fruit, seeming to the

young Prince Ivan (hidden in the bushes) the loveliest thing he has ever

seen. Greatly daring he captures her, but she begs to be released,

offering him a gift of one of her feathers.

Part 3.—She

departs. The garden is now filled with a band of maidens headed by a

Princess. They too dance with charming vivacity and have a game with the

golden apples. At dawn they disappear.

Part 4.—The Prince

is seeking them when suddenly there appears the monstrous retinue of

the evil spirit of the place, the demon king Kastchei The magic feather

preserves Ivan's life, but the Firebird also comes to his rescue. She

makes the bevy of wild Indians, warrior Turks, Chinamen, Clowns, Imps,

Hobgoblins, Ogres, and Apes burst into a frenzied dance. While they are

thus engaged she directs Ivan to smash a huge egg in a casket in which

is hidden the demon's life. This done the monster dies and the loathsome

creatures vanish. Ivan marries the princess.

The highly coloured

orchestration rather blinds one to the lack of any real "meat" in the

music. It is a positive relief on reaching Part 3 to encounter a genuine

tune, one which seems better than it actually is by reason of what has

gone before. Rhythmically the music is feverishly alive; melodically it

has to rely on actual or spurious folk tunes for sustenance. These sound

very like concessions. The final section with its blocks of harmonies

pushed this way and that makes a terrific din that fits the stage

picture, but is meaningless without. As a study for Petrouchka the music

has a definite interest and as all of us like a bit of "twopence

coloured" at times, these records will find a place in our cabinets.

Whatever

criticisms one may make of this Debussy–Scriabin–Stravinsky confection,

there are none to be made about the recording. Real oboe tone, that

floating incisive quality, is heard at last; the string background, the

occasional solo violin relief, the writhings and posturings of the wind

and brass are excellently reproduced. Everyone, at least, will be able

to take genuine pleasure in the Dance of the Princesses (Part 3)."

N.P., The Gramophone, April 1925, review of the Albert Coates recording of Stravinsky's The Firebird

MusicWeb International Review

Colourful, euphoric and above all, musical

I have been unhappy with Pristine Audio’s attempts to make early LPs

sound like digital CDs, but here we have a collection of acoustic

recordings and the transfer engineer is Ward Marston. I have not been

able to compare any other transfers of these same recordings – the

various sites offering early recordings for free download, such as

Shellackophile and Damian’s 78s, have not so far branched into Coates

very much. My impression is that we hear these ancient recordings about

as well as we are ever likely to. Readers who came to music in the 1960s

will remember that in those days the typical LP player also had

provisions for playing 78s. They invariably reproduced the discs with a

high level of scratchy hiss. On the rare occasions that I actually heard

some 78s played by a collector with an old player and a stock of fibre

needles, the hiss was gentler, more of a swish, and the music somehow

emerged from it remarkably well. That’s about how we get it here, but

with more detail than most of those old players could ever extract. When

the textures are relatively spare, as in the Ravel, it’s amazing how

much nuance and timbre comes across. But there’s no denying that

climaxes get strident, often confused, and the lack of depth is tiring

to the ear.

There are historical recordings where one can still

be caught up in an enthralling experience. There are others where the

musical lessons to be gleaned are so great that it is worth persevering.

But there are also some where one says “so that’s what it sounded like”

and passes on to other things.

These considerations were

particularly aroused by the Glinka and Rimsky-Korsakov items. This is

the sort of music that thrives on modern sound. Nor does it call for the

sort of interpretative insight reserved for the few. One can note that

Coates’s “Symphony Orchestra”, whatever it was, was a crack band. In

fast string passages he gets the sort of brilliant articulation

generally associated, in recordings from that period, with Mengelberg

and the Concertgebouw. Given that fast tempi go at a real lick, anyone

who expects to find slack orchestral standards in London of the 1920s is

in for a surprise. All the same, brilliant playing and high energy

levels are not unknown in more recent times, so one would need some

further reason for listening again. Not only do I not find this, I began

to feel, particularly in the Golden Cockerel music, that Coates’s

relentlessly up-front approach has its limits. It was interesting to

turn to a little-remembered version of this suite set down, I think for

Pye in the 1960s, by the London Philharmonic under Hugo Rignold - you

can download this from Rediscovery Paperbacks if you’re interested. The

LPO was not a virtuoso band at that time but there is a strong feeling

of affectionate enjoyment of the music by all concerned and a welcome

reminder that Rignold was a dab hand at music with a strong

story-telling content. This is important with music that risks seeming

the fruit of the drawing-board more than of inspiration.

Against

all odds, the performance that gave me most pleasure here was that of

the Stravinsky. With the music only thirteen years old, one rather

expects to find a bemused orchestra treading warily and none too

unanimously through the music on a note-by-note basis. Such early

recordings of Stravinsky certainly exist – some of them under the

composer’s own baton – but Coates’s band seems to have known the music

all its life. The score is not played as an extravagant piece of noisy

modernism but as a refined successor to Debussy, colourful, euphoric and

above all, musical.

It’s interesting to have this followed by

Kikimora, since Diaghilev had initially asked Liadov to compose the

Firebird ballet. Stravinsky himself is down as saying that Liadov would

never have had the energy to write a score like that. Strangely, in

Coates’s super-energetic hands the two composers’ styles seem remarkably

similar!

The Debussy is a slightly unsettled performance,

though Coates, a noted Wagnerian, makes the most of the Tristan quote.

In the Ravel we may note his skill in realizing every detail of the

orchestration but we may also note a pervasively heavy, over-regular

beat. How much more flexible is the 1949 Cluytens version, included in

an Andante compilation of historical Ravel performances, “Le jardin

fëerique” caressed and built up lovingly where Coates is almost

perfunctory. Was he at his best only in music that is fast and noisy?

This compilation was sent to me in tandem with another containing

Coates’s performances, from the same period, of Tchaikovsky’s 5th Symphony and Francesca da Rimini and Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances. For a rounded picture, the reader should now read my review of the companion disc.

Christopher Howell